Healthy Environments for Vulnerable Youth

Program Focus

Our team conducts both qualitative and quantitative research on a wide variety of social factors and how they are associated with the well-being of adolescents and young adults, with particular attention to vulnerable groups such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) youth, those with disabilities, and those who are overweight. Social factors include characteristics of the family and peer group (e.g. bullying experience); school resources, climate, and characteristics (e.g. presence of a gender/sexuality student organization); and features of the neighborhood or community (e.g. political climate, public policy). We capitalize on existing youth surveillance data to create multilevel quantitative datasets for hierarchical analysis. Qualitative methods with youth, parents, and professionals include interviews, focus groups, and other novel techniques.

Current Studies

Protection at the Intersection of Queer Teens of Color (PIQ-TOC)

This study: This University of Minnesota Medical School’s Department of Pediatrics research project, continues to identify significant disparities among youth at the intersections of sexual orientation, gender identity, and race/ethnicity in emotional distress, substance use, sexual and HIV-prevention behaviors, experiences of bias-based bullying, interpersonal protective factors, and numerous additional health concerns and experiences.

Our work is informed by intersectional factors that build our framework: we look closely at how young individuals experience power (or lack of) and privilege (or lack of), based on their interrelated social identities, in order to understand how these intersections confer risk and resilience to LGBTQ+ youth of color.

Eventually, we hope to recommend specific interventions and guidelines that center, support, and protect LGBTQ+ youth, particularly trans and gender-diverse (TGD) youth of color.

Background: Research shows that LGBTQ+ adolescents are at disproportionately high risk of poor health experiences, health outcomes, and health behaviors compared to their straight, cisgender peers.

In the field of healthy youth development, we see a gap in knowledge of how or if individuals’ intersectional identities (related to race, sexual orientation, gender identity, disability status, etc., e.g. TGD youth of color, youth who identify as TGD and also pansexual/queer) corresphttps://med.umn.edu/pediatricsond to the health and behavioral risks and protections they experience.

Because individual and social identities are experienced simultaneously (e.g. as a person who is both Black and trans), various forms of social oppression (e.g. racism and transphobia) may work together to differentially affect the health of LGBTQ+ people with multiple marginalized social identities.

We further hypothesized that living within these intersecting social identities may create unique challenges to – and strengths that promote – healthy development among youth.

We pose these specific research questions:

- What differences exist in bullying, risk behaviors, emotional distress, and protective factors among youth with different social identities?

- How do differing protective factors and other characteristics explain the above outcomes among youth with different social identities?

- What positive and negative experiences are uniquely relevant to the overlapping, simultaneous production of inequalities by LGBTQ+ identity, race/ethnicity, and other social identities?

- With which intersecting social identities do we see individual LGBTQ+ youth of color facing the greatest struggles?

The research: Our quantitative work builds on existing surveillance data from three adolescent health data sets: the Minnesota Student Survey (N ~122,000) and California Healthy Kids Survey (N ~1,042,000); plus the LGBTQ National Teen Survey (N ~17,000). Together, these provide us with very large samples of diverse populations and appropriate questions about social experiences.

Our qualitative research, in the form of interviews with over 65 LGBTQ+ youth, gives us detailed context on individual, interpersonal and community assets that informs our quantitative findings.

Since 2021, we have used these quantitative and qualitative methods to:

- Analyze combinations and intersections of social positions for LGBTQ+ adolescents.

- Analyze risk factors (e.g. bullying victimization) and protective factors (e.g. family support, inclusive sex education).

- Look at specific co-existing behaviors, experiences, and health conditions; emotional distress, substance use, sexual behaviors, HIV prevention behaviors, school absence, disordered eating, asthma, sports involvement, healthy youth development opportunities, sleep, and housing stability.

Recently Completed Studies

Adolescent Gender Diversity & Health (AGenDAH)

This research includes extensive analysis of a large, population-based sample of gender diverse youth (N=2168), takes a broad view of health influences and health care, and pairs this information with qualitative data from adolescent health care providers and youth. The goal of this mixed-methods study is to understand the health needs of gender diverse youth in order to develop and test training modules to be used in medical and nursing education in a future R01 application. The study has two specific aims: 1) Analyze data from the Minnesota Student Survey (MSS), a statewide surveillance system of adolescents’ health and related behaviors, which has recently been revised to include three measures regarding gender (biological sex, transgender identity, gender presentation). Analyses will focus on high risk health behaviors (i.e. substance use, sex behaviors, suicide involvement, bullying and prejudiced-based victimization), protective factors (i.e. internal assets, family support, school connection), health and health care utilization of gender variant youth, with comparisons to straight cisgender youth and youth who are diverse and lesbian, gay, bisexual and questioning (LGBQ, with whom transgender youth are often grouped for services and resources). 2) Conduct interviews with health care providers working with adolescents and with gender diverse youth to understand health care practices and needs of this population. Interviews with health care providers will include questions about their professional training regarding gender diverse youth, need for resources, and comfort and competence with this topic. Interviews with gender diverse youth will include questions regarding their experiences with health care professionals, information they would share with providers about their health needs, and feedback on findings from health care provider interviews.

Learn more about Adolescent Gender Diversity and Health (AGenDAH)

Policies & Practices to Prevent Bias-Based Bullying in Schools: A Multi-Method Pilot Study

Background: Bias-based bullying, or bullying based on personal characteristics such as race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, or body weight, has been identified as a key contributor to health disparities among youth of color; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) youth; and youth who are overweight or obese. Students who are the targets of bias-based bullying may not only experience emotional distress and physical health consequences associated with this type of bullying victimization, but they may also be less academically engaged and more likely to skip classes or full school days. As a result, bias-based bullying during adolescence can have life-long impacts on children’s healthy development, including physical health, social and emotional well-being, academic achievement, and employment. Although well-placed to intervene, educate, and prevent bias-based bullying, schools are struggling with a lack of clear guidelines and evidence-based practices that effectively reduce bias-based bullying. Given schools’ limited time and monetary resources, specific school practices that are responsive to the needs of both schools and youth most affected by bias-based bullying are critically needed.

This study: This study had two parts – a qualitative and a quantitative component.

Qualitative research: The aim of this component was to describe bias-based bullying experiences from the perspectives of youth, parents, and school personnel in Minnesota, focusing on youth of color, LGBTQ youth, and those who are overweight. We conducted 13 dyadic interviews (n=26 youth and parents), four focus groups (n=24 youth), and 7 school team interviews (n=19 staff members). Key findings include the following:

- While there were some experiences of “traditional” bullying, the majority of experiences included being the target of or overhearing slurs, name calling, and microaggressions that happened frequently but were not perpetrated by the same actor;

- Experiences of microaggressions (direct and overheard) were very common among students;

- Schools have policies and protocols in place to deal with bullying, but the experiences described by our participants typically did not meet the school’s formal definition of bullying (i.e. intention to harm, repeated action, power imbalance between actor and target), so often went unaddressed;

- Bias-based bullying adversely affected school climate and the health and wellbeing of vulnerable youth.

Quantitative research: The aim of this component was to explore whether schools that offer diversity education activities have lower rates of bias-based bullying among students compared to schools that do not offer these activities. Data came from two sources: the 2018 CDC School Profiles Survey (N=216 schools) and the 2019 Minnesota Student Survey (N=64,510 students). Multilevel logistic regression tested associations between diversity education activities (diversity clubs, lessons, or special events) and eight types of bias-based bullying among students (e.g. based on race/ethnicity/national origin, sexual orientation), with attention to differences across relevant demographic characteristics. Key findings include:

- Prevalence of bias-based bullying ranged from 7% reporting bullying due to religion, gender, and sexual orientation, to approximately 25% (due to weight and appearance);

- Experiences of bias-based bullying were significantly more common among youth with the relevant characteristic (e.g. students of color were more likely than white students to be bullied about race/ethnicity/national origin);

- Diversity education activities were common, with almost half offering all three types;

- Schools that offer a wider variety of diversity education opportunities had significantly lower odds of bullying about race, ethnicity, or national origin among boys of color, about sexual orientation for gay, bisexual and questioning boys, and about disability for boys with a physical health problem (similar findings were not found for girls).

Sharing findings: A brief summary of this work is available here (factsheet). Please contact Dr. Eisenberg (eisen012@umn.edu) if you are interested in having a team member present findings to school personnel in your organization.

Research & Education on Supportive & Protective Environments for Queer Teens

The goal of this study is to broaden and deepen our understanding of the family, peer, school and community environments that protect young LGB people from involvement in high risk health behaviors, including substance use, HIV risk behaviors and suicide behaviors. This research aims to 1) develop a theoretically grounded approach to promoting health among LGB adolescents based on in-depth knowledge of their community and school environments, and 2) link environmental data, collected using the Inventory, with existing population-based student data to identify factors at the individual, family, peer, school and community levels that protect LGB youth from involvement in health risk behaviors. “Go-along” interviews with 72 youth in diverse locations will be used to elicit in-depth information on LGB adolescents’ perceptions of supportive elements in their schools and communities; this information, in conjunction with published literature, expert review, and psychometric testing, will be used to create an LGB Environment Inventory to characterize policies, programs, resources and other supports for LGB youth that exist in these settings. The Inventory will then be used to measure indicators of support in 120 communities in Minnesota, British Columbia and Massachusetts, using publicly available materials (e.g. websites) and brief contacts with key informants (Aim 1). These community-level data will then be linked with existing student survey data from approximately 3,600 LGB adolescents in these same communities, which will include information about family, peer and individual supports, as well as health behaviors and demographic information (Aim 2). The following hypotheses will be tested: a) higher LGB environment scores for the community and school will be protective against health risk behaviors among LGB youth; b) greater family connectedness and support and a more supportive peer environment will be protective against health risk behaviors among LGB youth, and c) family, peer and individual-level factors will moderate the associations between the LGB environment (community and school) and the health risk behaviors of interest.

DoGPAH is home to Interdisciplinary Fellowship Programs that bring together a cadre of learners who lend their disciplinary perspective to the intensive shared fellowship experience. Several funding sources support the programs and also provide a range of fellowship focus options.

- Interdisciplinary Research Training in Child & Adolescent Primary Care

- Leadership Education in Adolescent Health (LEAH)

Learn more about the Interdisciplinary Fellowship Program

(italicized author name indicates trainee)

- Brown C. Eisenberg ME. McMorris BJ. Sieving R. Parents matter: Associations between parental connectedness and sexual health outcomes among transgender and gender diverse adolescents. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 52(4):265-273. 2020.

- Brown C. Porta C. Eisenberg ME. McMorris B. Sieving R. Family relationships and the health and well-being of transgender and gender diverse youth: A critical review. LGBT Health, available online Nov 10, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2019.0200.

- Eisenberg ME. Gower AL. Watson RJ. Porta CM. Saewyc EM. LGBTQ youth-serving organizations: what do they offer and are they protective against emotional distress? Annals of LGBTQ Public and Population Health, available online July 13, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/LGBTQ-2019-0008.

- Saewyc EM. Li G. Gower AL. Watson RJ. Erickson DJ. Corliss HL. Eisenberg ME. The Link between LGBTQ-Supportive Communities, Progressive Political Climate, and Suicidality Among Sexual Minority Adolescents in Canada. Preventive Medicine, available online July 9, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106191.

- Gower AL. Watson RJ. Erickson DJ. Saewyc EM. Eisenberg ME. LGBQ Youth’s Experiences of General and Bias-Based Bullying Victimization: The Buffering Role of Supportive School and Community Environments. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, available online Feb 21, 2020. DOI: 10.1007/s42380-020-00065-4

- Watson RJ. Park M. Taylor A. Fish J. Eisenberg ME. Saewyc EM. Associations Between Community-Level LGBTQ-Supportive Factors and Substance Use Among Sexual Minority Adolescents. LGBT Health, available online January 27, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2019.0205

- Porta CM. Gower AL. Brown C. Wood B. Eisenberg ME. Perceptions of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Minority Adolescents About Labels. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 42(2):81-89. 2020.

- Eisenberg ME. McMorris BJ. Rider GN. Gower AL. Coleman E. “It’s kind of hard to go to the doctor’s office if you’re hated there.” A call for gender-affirming care from transgender and gender diverse adolescents. Health & Social Care in the Community, 28(3):1082-1089. 2020.

- Shramko M. Gower AL. McMorris BJ. Eisenberg ME. Rider N. Intersections between multiple forms of bias-based bullying among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer youth. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, available online October 30, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-019-00045-3.

- Eisenberg ME. Denight E. McRee AL. Brady SS. Barnes AJ. Homelessness Experiences & Gender Identity in a Population-Based Sample of Adolescents. Preventive Medicine Reports, available online Sept 5, 2019. DOI: doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100986

- Eisenberg ME. Erickson DJ. Gower AL. Kne L. Watson RJ. Corliss H. Saewyc E. Supportive community resources are associated with lower risk of substance use among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning adolescents in Minnesota. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, Apr;49(4):836-848. 2020.

- Gower AL. Valdez C. Watson R. Eisenberg ME. Mehus CJ. Saewyc EM. Sullivan RT. Corliss H. Porta CM. First- and Second-Hand Experiences with Bullying, Harassment, and Violence among LGBTQ Youth. Journal of School Nursing, available online July 23, 2019. DOI: 10.1177/1059840519863094.

- Brown C. Frohard-Dourlent H. Wood B. Saewyc E. Eisenberg ME. Porta CM. “It makes such a difference”: An examination of how LGBTQ youth talk about personal gender pronouns across North America. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, available online June 27, 2019. doi: 10.1097/JXX.0000000000000217.

- Gower AL. Saewyc EM. Corliss HL. Kne L. Erickson DJ. Eisenberg ME. The LGBTQ Supportive Environments Inventory: Methods for Quantifying Supportive Environments for LGBTQ Youth. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 31:3, 314-331. 2019.

- Taliaferro LA. Harder BM. Lampe N. Carter SK. Rider GN. Eisenberg ME. Social Connectedness Factors that Facilitate Use of Healthcare Services: Comparison of Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming and Cisgender Adolescents. Journal of Pediatrics, 211:172-8. 2019.

- Eisenberg ME. Gower AL. McMorris BJ. Rider GN. Coleman E. Emotional distress, bullying victimization, and protective factors amongtransgender and gender non-conforming youth in urban, suburban, town and rural locations. The Journal of Rural Health, 35(2):270-281. 2019.

- Rider GN. McMorris BJ. Gower AL. Coleman E. Brown C. Eisenberg ME. Perspectives from Nurses and Physicians on Training Needs and Comfort Working with Transgender and Gender Diverse Youth. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, available online Feb 28, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2018.11.003.

- Eisenberg ME. Gower AL. Rider GN. McMorris, BJ. Coleman E. At the Intersection of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity: Variations in Emotional Distress and Bullying Experience in a Large Population-based Sample of U.S. Adolescents. Journal of LGBT Youth, available online Feb 10, 2019. DOI: 10.1080/19361653.2019.1567435.

- Rider GN. McMorris BJ. Gower AL. Coleman E. Eisenberg ME. Gambling Behaviors and Problem Gambling: A Population-Based Comparison of Transgender/Gender Diverse and Cisgender Adolescents. Journal of Gambling Studies, available online October 22, 2018 DOI:10.1007/s10899-018-9806-7

- Gower AL. Rider GN. Brown C. McMorris BJ. Coleman E. Taliaferro LA. Eisenberg ME. Supporting Transgender and Gender Diverse Youth: Protection Against Emotional Distress and Substance Use. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 55(6):787-794. 2018.

- Gower AL. Rider GN. McMorris BJ. Eisenberg ME. Bullying among LGBTQ Youth: Current and Future Directions. Current Sexual Health Reports, available online Sept 3, 2018. DOI: 10.1007/s11930-018-0169-y

- Taliaferro LA, McMorris BJ, Eisenberg ME. Connections that moderate risk of non-suicidal self-injury among transgender and gender non-conforming youth. Psychiatry Research, 268:65-67. 2018.

- Gower AL. Rider GN. Coleman E. Brown C. McMorris BJ. Eisenberg ME. Perceived Gender Presentation among Transgender and Gender Diverse Youth: Approaches to Analysis and Associations with Bullying Victimization and • Emotional Distress. LGBT Health, available online Jun 19, 2018. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2017.0176.

- Wolowic JM. Sullivan R. Valdez CA. Porta CM. Eisenberg ME. Linking LGBTQ youth to supportive resources. International Journal of Child, Youth, and Family Studies, 9(3):1-20. 2018.

- Taliaferro LA. McMorris BJ. Rider GN. Eisenberg ME. Risk and Protective Factors for Self-Harm in a Population-Based Sample of Transgender Youth. Archives of Suicide Research, available online Feb 20, 2018. DOI: 10.1080/13811118.2018.1430639

- Rider GN. McMorris B. Gower AL. Coleman E. Eisenberg ME. Health and Care Utilization of Transgender/Gender Non-Conforming Youth: A Population-Based Study. Pediatrics, 141(3): e20171683. 2018.

- Eisenberg ME. Mehus C. Saewyc E. Corliss H. Gower AL. Sullivan TR. Porta CM. Helping young people stay afloat: A qualitative study of community resources and supports for LGBTQ adolescents in the U.S. and Canada. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(8): 969-989. 2018.

- Gower AL. Forster M. Gloppen K. Johnson AZ. Eisenberg ME. Connett JE. Borowsky IW. School Practices to Foster LGBT Supportive Climate: Associations with Adolescent Bullying Involvement. Prevention Science, available October 14, 2017. DOI 10.1007/s11121-017-0847-4

- Eisenberg ME. Gower AL. McMorris BJ. Rider GN. Shea G. Coleman E. Risk and Protective Factors in the Lives of Transgender/Gender Non-Conforming Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61:521-526. 2017.

- Porta CM. Singer E. Mehus CJ. Gower AL. Fredkove W. Eisenberg ME. LGBTQ Youth’s Views on Gay-Straight Alliances: Building Community, Providing Gateways, and Representing Safety and Support. Journal of School Health, 87:489-497. 2017.

- Mehus CJ. Watson RJ. Eisenberg ME. Corliss H. Porta CM. Living as an LGBTQ youth and a parent’s child: Overlapping or separate experiences. Journal of Family Nursing, 23(2):175-200. 2017.

- orta CM. Gower AL. Mehus CJ. Yu X. Saewyc E. Eisenberg ME. "Kicked out": LGBTQ youths' bathroom experiences and preferences in the US and Canada. Journal of Adolescence, 56:107-112, 2017.

- Porta, CM. Corliss H. Wolowic JM. Johnson AZ. Fogel KF. Gower A. Saewyc EM. Eisenberg ME. Go-along interviewing with LGBTQ youth in Canada and the United States. Journal of LGBT Youth, 14(1):1-15. 2017.

- Wolowic J. Heston L. Saewyc E. Porta C. Eisenberg M. Chasing the rainbow: lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer youth and pride semiotics. Culture, Health and Sexuality, available online November 10, 2016. DOI: 10.1080/13691058.2016.1251613

- Bucchianeri MM. Gower AL. McMorris BJ. Eisenberg ME. Youth Experiences with Multiple Types of Prejudice-based Harassment. Journal of Adolescence, 51, 68-75. 2016.

Division of General Pediatrics and Adolescent Health

717 Delaware St. SE

Minneapolis, MN 55414

|

Marla Eisenberg, Sc.D., M.P.H. (Professor, DoGPAH) |

|

Amy Gower, Ph.D. (Research Associate, DoGPAH) |

|

Barbara McMorris, Ph.D. (Associate Professor, School of Nursing) |

| |

Nic Rider, Ph.D. (Assistant Professor, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health) |

| |

Marizen Ramirez, Ph.D., M.P.H. (Associate Professor, School of Public Health) |

| |

Camille Brown, PhD, R.N. (Assistant Professor in the School of Nursing, Starting 9/2021) |

| |

Yoon-Sung (Teddy) Nam, M.P.H. (Doctoral Student, School of Public Health) |

|

De’Shay Thomas, MSW, Ph.D. (Post-doctoral Associate) |

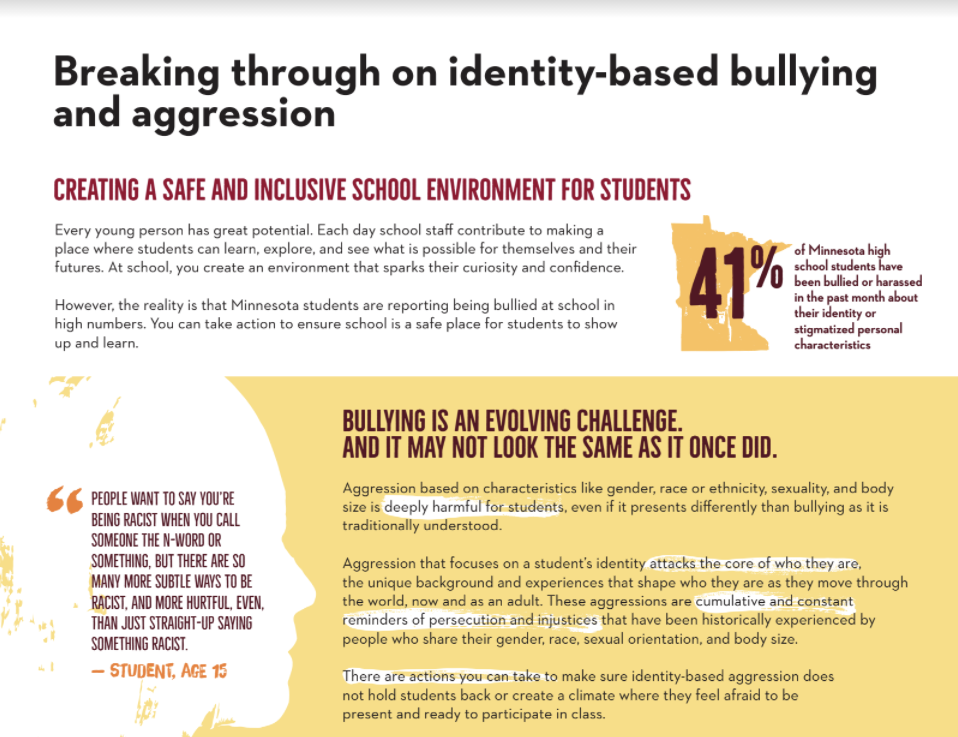

CREATING A SAFE AND INCLUSIVE SCHOOL ENVIRONMENT FOR STUDENTS

Every young person has great potential. Each day school staff contribute to making a place where students can learn, explore, and see what is possible for themselves and their futures. At school, you create an environment that sparks their curiosity and confidence. However, the reality is that Minnesota students are reporting being bullied at school in high numbers. You can take action to ensure school is a safe place for students to show up and learn.

Principle Investigator

Marla Eisenberg, ScD, MPH

Department of Pediatrics

Division of General Pediatrics and Adolescent Health