Department of Emergency Medicine Trains Medical Students Using Online, Simulated Patient Scenarios

Physically experiencing the often-noisy, fast-paced and team-oriented environment of an emergency department helps medical students fully grasp the medical decision-making and critical-thinking skills needed to serve a hospital’s most vulnerable patients. But, these clinical experiences abruptly halted at the onset of COVID-19, sending medical students home to learn virtually—all across the nation.

“We could no longer get our students into the emergency department, which is the very essence of our rotation,” said Mary Ann McNeil, MA, NRP, program director in the Department of Emergency Medicine. “When we were designing the new curriculum, the first thing we did was start with virtual simulation.”

In true emergency form, the department urgently revamped its four-week rotation of the EMDD7500 course, an advanced core curriculum for third- and fourth-year medical students. Traditionally, the course provides medical students with 12 to 14 shifts in local emergency departments and takes them to the University’s bequest lab to practice emergency procedures—from chest tube insertions to setting up an IV.

“For a physician in training to be able to do actual procedures on human tissue in the bequest lab, it’s the best training there is and the safest training there is,” McNeil said. “While they are missing out on patient interaction and learning how things go in an emergency department, a big part of our training already involved a lot of virtual simulation. We did so much before all of this started that getting into that which is virtual for us has certainly been work but not something we didn’t understand.”

McNeil discovered Oxford Medical Simulation, a virtual reality medical simulation training, and offset some of the costs to purchase a year-long license with a $10,000 COVID-19 Medical Innovation Grant from the Medical School. This online coursework, now a central part of EMDD7500, features 10 simulated scenarios that medical students have completed safely from home.

“We have one of our residents as the facilitator, and then the students work as a team like they would in the emergency department to care for this patient. Usually a scenario is 10 to 15 minutes, and then they do debriefing,” McNeil said. “Then, the students get the rest of the scenarios to finish on their own, which we can track through Oxford’s assessment piece. We’ve been really pleased with the evaluations from the students. They report this to be very helpful in developing their assessment skills.”

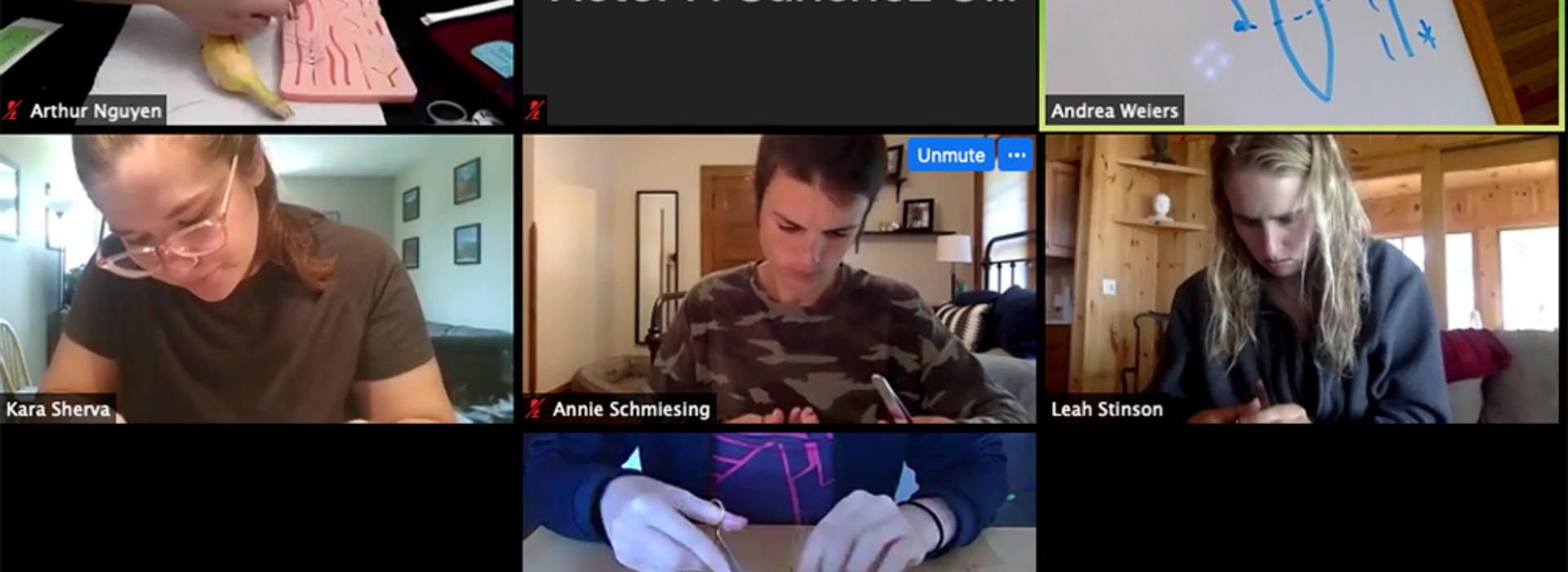

Beyond the use of Oxford Medical Simulation, McNeil found new ways to help medical students fine-tune one of the rotation’s student-favorite practices—suturing. Before the start of the rotation, she mailed suture kits to every enrolled medical student.

“All they need is either pig feet or dolls, depending on what they have access to,” McNeil said. “We bring them on Zoom, have them turn their cameras so that it looks directly down on their hands and then practice the different ties. We have been delighted that the students have taken to this like ducks to water.”

After completing two weeks of the rotation virtually this summer, that same group of medical students will experience two weeks, or about seven shifts, physically in the emergency department this fall.

“It’s as close to the clinical setting as you could possibly be. It certainly is not as much as we would like, but it’s the best we can all do,” McNeil said. “I’ve been so impressed with how these students have stepped up to the plate and have said, ‘Give me more. I want to do this. I want to do that. Give me something other than reading.’ They’ll be okay.”