Promoting Excellence During COVID-19

THE YEAR 2020 HAS BEEN UNLIKE ANY OTHER IN RECENT HISTORY, challenging humanity with the deadliest global pandemic since the Flu Pandemic of 1918. The COVID-19 pandemic, above all things, has been a human and economic tragedy. Healthcare workers have been heroic in their fight against the virus, tirelessly providing patient care in the face of danger. Preventing the virus’ spread while safely caring for patients required drastic, unprecedented changes within the University of Minnesota Medical School, M Health Fairview partnership, the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, HealthPartners, CentraCare, and the department’s affiliate sites. While the human toll of COVID-19 is substantial, the spirit of resiliency, connection, and compassion have inspired hope to move forward together.

On March 6, the first known case of COVID-19 was confirmed in the state of Minnesota. Healthcare organizations and professionals took note, creating contingency plans to deal with the potential influx of patients and disruption of the care system. Orthopedics was no exception, and in a move aligned with other major professional organizations, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) canceled its annual meeting on March 10. While cancellation of such a large event was in the best interest of patients and frontline healthcare workers, it foreshadowed the drastic changes to come. After Minnesota Governor Tim Walz declared a peacetime emergency on March 13, it was clear some of the contingency plans might go into effect.

A TEAM-BASED APPROACH TO CARE

The department’s city-wide faculty began preparing for potential scenarios (like handling a positive COVID-19 case within the workforce), resulting in a plan to divide into care teams to prevent community spread. At that time, case fatality ratios were imprecise and varied wildly by country, ranging anywhere from 0.1 to more than 25 percent, while large-scale testing was still in its infancy. With so many unknowns, it was

imperative to consider the implications of a worst-case scenario and prevent collapse of the entire workforce.

“That was a challenging time because there was so much conflicting information,” says Professor and Chair of Orthopedics at Hennepin County Medical Center (HCMC), Andrew Schmidt, MD. “As physicians, we

understand the potential impact of viral spread, but it was so new, and it was hitting us hard.”

HCMC was the first affiliate site to transition into a team-based care model around March 12 after preparing for several weeks. On March 15, Professor and Department Head Denis Clohisy, MD, along with vice chairs Ann Van Heest, MD, and Elizabeth Arendt, MD, eliminated division of care by subspecialty at the M Health Fairview University of Minnesota Medical Center (UMMC) and assigned physicians, residents, and advanced practice providers into three teams. This emergency protocol, called the COVID-19 rotation, was set to last at least six weeks spanning from March 18-May 3, with the potential to continue beyond.

During the rotation, faculty limited work to a single health system to mitigate potential spread. UMMC’s teams worked one-week rotations in person with two off for self-isolation for 14 days – the accepted length of time from contact to symptoms of COVID-19. This allowed anyone exposed to the virus time to quarantine without placing additional stress on the workforce, since testing was not widely available. Ideally, teams had representation from major subspecialty areas and a variety of seniority levels, responsible for orthopedic clinics, emergencies or consults, surgeries, and floor work. Additional resident or physician assistant support for large, complex cases could be requested through the team’s assigned captain. The department’s other partner sites, including TRIA, Regions, CentraCare, and Gillette, established similar team-based models.

While UMMC’s model had many strengths, a large workforce was needed to divide into three teams. The Minneapolis VA adapted the concept and formed two teams, one that managed telehealth work while in self-quarantine and one that handled in-person clinical work. Named Operation Bravo Zulu (a military expression for “good job”), this approach to team care commenced on March 23.

ELECTIVE PROCEDURES POSTPONED

After the first documented incidence of COVID-19 community spread in Minnesota, elective surgeries were postponed at health systems, including M Health Fairview, HealthPartners, Allina Health, and Mayo Clinic on March 18. In the M Health Fairview system, a transition to virtual visits for nonurgent care was the first of many steps to keep physicians and patients safe and healthy.

“We closed the clinics, established a process to discuss problems virtually, saw patients in-person at the urgent care Walk-In Clinic if their condition was deemed critical, and only performed necessary surgeries,” says Professor and M Health Fairview Musculoskeletal Service Line Director Elizabeth Arendt, MD. “The goal was to reduce non-urgent orthopedic cases presenting at the emergency room, preserve resources, and mitigate potential community spread.”

Similar measures were adopted across the department’s partner sites. At Regions, the same-day surgery center was closed altogether, so the orthopedic team partnered with TRIA-Woodbury to arrange urgent surgeries, like treating certain fractures and infections that didn’t require hospitalization.

“That was a crucial partnership to provide the best care possible,” says Assistant Professor Sarah Anderson, MD, Regions’ vice chair of orthopedics and site director. While Anderson says most patients were understanding and accommodating as they transitioned to virtual care, canceling and rescheduling surgeries could be challenging for administrative teams and frustrating for patients. “I think the biggest challenge for providers was prioritizing which conditions and patients to treat,” Anderson says. “It was difficult determining what was the most important when considering finite resources.”

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons assembled criteria – including length of surgery, patient age, comorbidities, and more – to guide triaging care. “Fractures and infections come to mind in terms of time-sensitive orthopedic care, but there are gray areas,” explains Franklin Sechriest, MD, associate professor and chair of orthopedics at the Minneapolis VA. “While rotator cuff tear repair is considered an elective

procedure, the patient experiences irreversible damage if it’s neglected. There were a lot of novel challenges within our healthcare system to determine what constituted urgent, time-sensitive care and what could truly wait.”

VIRTUAL VISITS BECOME REALITY

On March 30, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services introduced a number of new policies to help hospitals and physicians transition to virtual care, including reimbursement for audio-only telephone visits.

“Early on, virtual visits allowed us to stay in contact with patients, provide advice, and try our best to manage problems,” says Associate Professor Bradley Nelson, MD. “I think the pandemic accelerated the acceptance of virtual care by providers, payers, and patients, and using it for some visits will become routine in the future.”

Patients across the department’s sites often travel a significant distance for subspecialty orthopedic care. Telemedicine saves time and the associated cost of traveling and can be conveniently accessed from home or a nearby clinic. “Patients have the option to go into their local clinic, have X-rays, and send images, all while maintaining their provider in the Twin Cities,” Anderson says.

At HCMC, telemedicine resources were rapidly deployed and became invaluable for nursing home patients who needed routine postoperative check-ups, which even in normal circumstances can be difficult and costly to arrange. Due to COVID-19, many nursing homes would not let their residents leave their facility – so HCMC staff did the visits virtually. In some cases, Schmidt was able to see these patients along with their physical therapist or nurse on the same call. “While it was forced on us, telemedicine has been a much-needed development,” Schmidt says. “It really saves a lot of time, and it’s better than how we used to do it.”

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Minneapolis VA pioneered a referral line for primary care physicians at outreach clinics in Minnesota and parts of the Dakotas to reach an orthopedic surgeon during business hours. The “Bone Phone” started as a way to give real-time orthopedic assistance, and if needed, could be linked into a telemedicine visit immediately. Until March, the Bone Phone was the extent of the Minneapolis VA’s orthopedic telemedicine program. “At the beginning of the pandemic we expanded its reach to a huge geographic region including all of the Dakotas up to Duluth, MN,” Sechriest says. “We start the plan of care by talking on the phone, connecting via telemedicine, or expediting their care in-person. In other words, we found a way to use telemedicine for urgent, time-sensitive needs.”

Patients can also download the VA Video Connect (VVC) app to interface with providers via phone or computer. Visitor limits at the onset of the pandemic meant that some patients couldn’t have their families present throughout the entire care process. Now, VVC gives them an opportunity to talk about a potentially high-risk surgery with family by their side. “I’m incredibly proud of our telemedicine programs because I didn’t think it was possible,” Sechriest says.

At CentraCare in St. Cloud, MN, the orthopedic team began the transition to virtual care in March, which was a challenge because they hadn’t utilized a platform for phone or video visits before. “Thankfully, our Epic and IT teams quickly implemented the technology to allow clinic visits to continue,” says Senior Director of Orthopedics Craig Henneman, MBA. “The experience has been seamless for patients.”

While the future of telemedicine is bright, it has limitations. One barrier to its widespread use is caring for patients whose permanent residence is outside of Minnesota, since there are laws around out-of-state care delivery without a license to practice in that state. Early on in the pandemic, these licensing rules were waived – but by late summer, states began to limit virtual medicine outside their borders. Telemedicine is also still in its infancy as the technology to optimize it continues to develop. For example, the camera on a patient’s phone and internet connection can sometimes be barriers to conducting the equivalent of a physical examination.

“I would never make a surgical decision based off of a telemedicine visit alone,” Sechriest explains. “There are limits when it comes to new patient evaluations and major decisions.” While unlikely to completely replace in- person visits anytime soon, telemedicine has proven to be an untapped resource. “There are many things physicians can’t do virtually,” says Arendt. “However, when applied appropriately, telemedicine saves time, money, and travel. I do think it’s here to stay.”

MAINTAINING THE EDUCATION MISSION

Improving and expanding the quality of education for residents and medical students has always been at the forefront of the department’s mission, and maintaining the educational legacy virtually was imperative at the onset of the pandemic. The education team was quick to embrace virtual learning, transitioning Grand Rounds and core curriculum to a virtual format on March 16. While hands-on training is a vital element of any orthopedic surgery residency program, the education team has found ways to deliver quality education outside of the operating room.

“We’ve kept up, if not intensified our education program throughout the COVID-19 pandemic,” says Professor and Residency Program Director Ann Van Heest, MD. “We initiated an accelerated lecture series and transitioned to remote Grand Rounds and core curriculum sessions to enhance resident learning. We also started virtual rotations for medical students interested in our program, so our circumstances have allowed us to expand to a larger audience.”

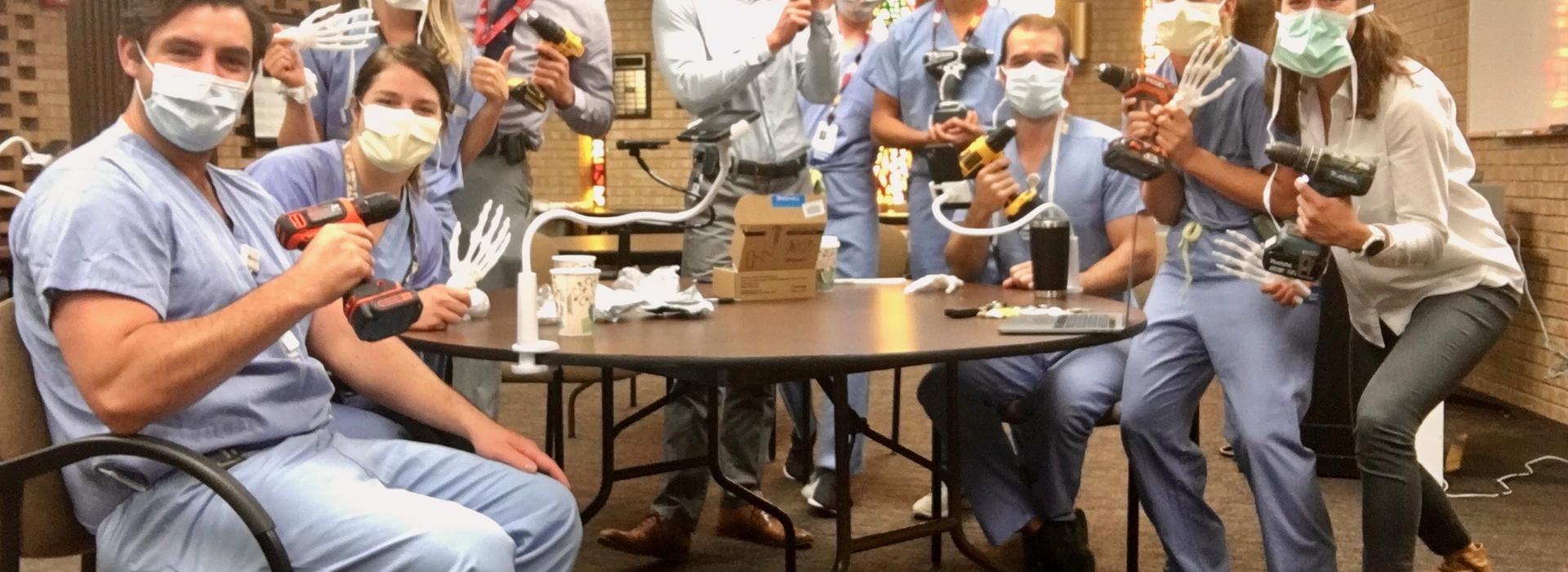

In August, the department hosted the first-ever virtual James House, MD, Hand Skills Lectureship and Educational Workshop, a long-standing simulation program supported by Professor Emeritus James House, MD. During the simulation, residents learned scaphoid, Bennet and phalanx fracture pinning using a 3D-printed hand model. A Medical School COVID-19 Medical Education Innovation Grant – spearheaded by associate professors Alicia Harrison, MD, and Marc Tompkins, MD, and in partnership with the Earl E. Bakken Medical Devices Center (MDC) – funded the 3D printing.

The grant also funded a web-based program that allows users to observe a surgery on a split-screen with the related 3D anatomy. The 3D model can be manipulated and studied on a computer or using a virtual reality (VR) headset. This helps trainees familiarize themselves with the overall shape and anatomical relationships of bones. The program can also be used in surgical planning, templating, and practicing implant placement using the patient’s anatomy captured from a CT scan. Still, Van Heest says it’s imperative that skills learned virtually can be transferred to actual patient care.

“When you’re first training to be a surgeon, learning the basic skills and steps of the surgery is important,” Van Heest explains. “If those basics can be learned in a lab versus an operating room, trainees are more efficient because they already know the fundamentals of the procedure.” The department incorporates a number of simulated labs into the residency program, which have transitioned to virtual or mixed formats throughout 2020. G1 Skills Week, for example, took place in a socially distanced, masked environment.

Despite the unusual circumstances, residents still received a day of instruction and hands-on practice of foundational orthopedic skills (like simulated wire navigation, fracture reduction with external fixator placement, and micro-suturing) at each clinical rotation site. Other key programs, such as the Perry Initiative, took place in smaller, socially distanced settings with proper personal protective equipment (PPE). The annual workshops expose young women to careers in orthopedic surgery and biomechanics, and this year, 25 students joined the department for two nights of interactive instruction. While adjusting to the new learning environment has required innovation and flexibility, the department’s education team has continued to move the mission forward by providing expanded learning opportunities for trainees.

PREPARING FOR WORST-CASE SCENARIOS

After reports that orthopedic surgeons in New York City were retasked to care for COVID-19 patients, the department’s University of Minnesota Physicians faculty were given opportunities for redeployment to other areas of patient care in the event of workforce shortages. At CentraCare, a labor pool was created to best utilize non-provider staff and physicians depending on their expertise and licensure. “We indicated what we’d be comfortable doing, like working in the intensive care unit, doing triage, or redeploying elsewhere,” says Nelson. “I think many of the orthopedic surgeons in the department were willing to work in those environments if the need arose.”

Preserving resources was imperative across sites, and the best way to protect PPE and operating room access was to treat critical conditions only. While the criteria for care varied across institutions, emergency situations generally included fracture management, infections, and tendon lacerations. “Our responsibility as healthcare providers was to preserve resources, like personal protective equipment and operating room capacity, in the event COVID-19 cases spiked,” explains Nelson.

Early on, leadership planned for a surge as if it was going to happen. Initially, TRIA sent all its anesthesia machines to Methodist Hospital (a designated COVID-19 care center), meaning surgeries couldn’t continue at the site. At Regions, there were concerns about potential PPE shortages and N-95 masks were reserved for positive patients. In response, the orthopedic trauma research team put their 3D printing skills into action to print N-95 masks for all the orthopedic frontline providers. Anderson and her children are avid sewers, and made masks for providers at their site. With so much uncertainty, she also started a weekly encouragement email to lift the team’s spirits and showcase the work being done to support frontline healthcare workers.

From the state management level, Schmidt posits separating trauma and COVID-19 centers would have been more efficient, since it was challenging to manage both. By late April, HCMC’s capacity for trauma care decreased and there was a period during which their ICUs were completely full, resulting in activating plans to overflow into makeshift ICUs. He and Associate Professor Alicia Harrison, MD, appeared on Fox 9 on April 2 to urge the public to abstain from risky activities that could result in hospitalization.

“We tried to educate the public about avoiding situations that could lead to a hospitalization, because hospitals are understaffed and caring for COVID-19 patients,” Schmidt says. “We were really worried that if trauma continued, we wouldn’t be able to function as a trauma center and a COVID-19 hospital since our beds were full and our operating room resources were limited. Had trauma been at its usual level, we would not have been able to admit those patients.”

HCMC and Methodist Hospital ended up being the busiest in terms of inpatient COVID-19 patient numbers, followed by Bethesda. In a forward-thinking move, M Health Fairview designated Bethesda Hospital in St. Paul, MN, as the COVID-19 specialty care facility and began moving positive patients on March 23. It was the first COVID-19- only hospital in Minnesota (and one of the first in the nation), using a cohort model to bring all the patients and healthcare experts together in the same place. The model reduced potential spread to noninfected patients and allowed providers to become well-versed in COVID-19 care and best practices. It also freed up capacity at M Health Fairview’s other hospitals, mitigating the additional strain on resources.

“M Health Fairview was very proactive in opening Bethesda as a COVID-19 hospital, which allowed them to maintain their capacity at the University of Minnesota Medical Center and Fairview hospitals,” Schmidt says. “At HCMC, we didn’t anticipate having as many COVID-19 patients as we did, but given our role as a safety net hospital, it was not surprising.”

With events unfolding on the east and west coasts of the country, the mental health of providers was also a top departmental priority. MinnRAP (Minnesota Resilience Action Plan) was established in early April and spearheaded in the department by Assistant Professor Heather Bergeson, MD. The program partnered faculty for regular check-ins to foster connection and resilience, in addition to an opportunity to share fears and anxieties that healthcare workers collectively experience. The program was designed and administered through the Department of Anesthesiology and the Department of Psychiatry with guidance from U.S. Army Commander Brian McGlinch, MD.

Thankfully, the department’s orthopedic surgeons were not called upon to redeploy in other areas of patient care, and all its sites were able to manage critical conditions in a timely manner. By mid-summer, PPE supplies were adequate and protocols around use of more protective N-95 masks were loosened. Restoring the Practice As COVID-19 cases showed signs of hitting a plateau in mid-June, safely restoring the practice and expanding patient care was a top priority.

At the U, a Practice Restoration Committee was formed with faculty volunteers developing expertise in various areas. Assistant Professor Patrick Morgan, MD, became the authority on testing protocols, while Assistant Professor Patrick Horst, MD, became the go-to for operating room changes. While operations have ramped up since May, M Health Fairview’s allowed daily clinic patient volumes are reduced due to social distancing. Similarly, some patients have chosen to delay non- essential surgery since the impact of contracting COVID-19 postoperatively is not well-understood at this time.

At the Clinics and Surgery Center, where outpatient orthopedic surgeries are performed, patients come into the building with other medical problems and may have respiratory illnesses. Because of this, ramping back up to previous volumes is harder to manage than at an orthopedic-only facility like TRIA. At both the U and TRIA, patients practice social distancing, are screened for COVID-19 at the front door and need to test negative prior to surgery, wear face masks, and limit the number of visitors. “The practice restoration plan went in phases aligned with the Minnesota Governor’s orders on elective surgery,” explains Nelson. “It was a lockstep approach to gradually expand the scope of care.”

While CentraCare has been a hub for Central Minnesota, it’s managed to maintain its workflow and patient experience with non-provider staff working remotely since March. In June, the orthopedic team began moving the needle towards half in-person and half virtual visits. Since going back to regular hours on July 1, their volumes have returned to normal in terms of capacity. “I’m truly impressed with the patient flow,” Henneman says. “While a portion of our team is no longer on site, the care is just as good, if not better than pre- COVID.” Even with social distancing in place, CentraCare saw its highest clinic volumes since the program’s start in July and August. “CentraCare has done a great job planning for a second surge,” he adds. “They’ve built a structure to not only continue inpatient surgeries, but also to continue elective outpatient surgeries on a consistent basis without delaying care, or having a small delay in comparison with the first months.”

While patients were initially very understanding of new protocols, there has been some frustration due to a backlog of surgeries as they begin using the healthcare system again. “We’re certainly not back to normal, but we’re trying to maintain a typical orthopedic practice with an emphasis on safety,” Nelson explains. “At TRIA, we used the time we weren’t busy to reexamine our operating room schedule to be more efficient when we reopened, and I think that’s gone very well.” Nelson adds that physicians felt a sense of urgency to get back up and running to limit the financial hardship on their teams. “The financial impact we felt as some of our team members were furloughed or had hours reduced was a primary motivating factor to restore the practice as efficiently and safely as possible,” he says.

The Regions team has gradually added more services and are currently at about 90 percent of their pre-COVID block structure in the operating room. They’ve leveraged a mix of virtual and in-person visits to manage reductions in capacity and staffing. “Clinically speaking, our volumes are rapidly getting back to where they were, and our faculty were at about 90 percent of the production from last summer at the same time,” Anderson says. “The dilemma now is going to be cost containment.”

At the Minneapolis VA, Operation Bravo Zulu ended on July 1 and Operation Ortho C.H.A.O.S. (Can Have Another Outstanding Solution) began, remaining in effect through July 31. As part of the operation, clinics could safely increase capacity by 25 percent more than since the pandemic began, and select elective cases resumed. Since August, the Minneapolis VA has been working on restoring its practice while also leveraging telemedicine to meet patient needs virtually. “The most challenging part of the practice restoration plan is triage - how to achieve the greatest good, for the greatest number, and the greatest need safely,” Sechriest says.

Another major consideration is identifying patients with numerous comorbidities that might defer treatment until a vaccine is available. In the past, the Minneapolis VA relied on nursing homes for extended postoperative rehabilitation for older patients. Now, extended care facilities and nursing homes have been established as a risk factor for poor COVID-19 exposure outcomes. “Some of the most needful and disabled patients, in terms of function, may have a high comorbidity profile and high likelihood of requiring an extended care facility,” Sechriest explains. “In certain circumstances, that patient may be safer deferring surgery because of the unknowns of COVID-19 exposure postoperatively. It’s very frightening.”

Because of this, the Minneapolis VA’s ramp-up plan started with the healthiest patients and least invasive surgeries in an ambulatory setting. From there, they graduated to inpatient procedures for those with healthy profiles and are now expanding to patients who have been waiting for care. “It’s been an incredibly challenging puzzle, and we’ve had to come up with a myriad of solutions,” he adds. “We’re moving forward and continuing to do a high volume of surgery that’s increasing weekly, but until we have a treatment or vaccine, I do believe there are some patients who need to wait.”

While the Minneapolis VA is proactive in educating patients around potential risks, there are unknowns for both patients and orthopedic surgeons performing elective procedures. Still, every decision is supported by best practices in patient care and safety, carried out with the diligence of a military operation. “Major wars are won by individual soldiers making decisions based on real- time data, taking risks, and doing the right thing at the right time,” Sechriest says. “That’s the approach we took, and we’ve done well because of our teams.”

HCMC first began ramping up by opening its surgery center, which included some sports medicine and arthroscopy services. By mid-May, orthopedics transitioned back to a full team structure and gradually returned to a regular schedule, although many visits are now conducted using telemedicine and meetings take place virtually. While Schmidt was booked for total joint cases three months in advance prior to COVID-19’s onset, he has been able to catch up and perform surgeries on eligible patients. While that’s good news for patients and providers, access to testing has become a concern during the fall months. Many of the clinical staff have school-aged children, and as some schools open up to in-person learning, it may be difficult to determine if symptoms are a common cold or COVID-19.

The other remaining challenge is keeping elective surgeries going, trauma centers capable of meeting trauma needs, and separating COVID-19 centers. “We’ve got to figure out a way to keep routine medical care going while also taking care of COVID-19 patients, because it did shut down the entire medical system for a while,” Schmidt says. “That’s probably the biggest thing we can improve as a system in the future.”

Schmidt believes that surgeons tend to thrive in emergency situations, and while he’s had to lead through the pandemic, it’s been possible because of the staff and faculty at the U, HCMC, and the department’s partner sites. “It’s easy to lead when you have high- functioning, motivated, creative people on your team,” he says.

NAVIGATING THE NEW NORMAL

The COVID-19 pandemic has reshaped how Americans go about their professional and personal lives, how they’re educated, and receive healthcare. Teachers who once engaged with students in the classroom transition to communicating through screens. Families reconsider how to celebrate holidays while being mindful of social distancing. In the department, the administrative offices are overwhelmingly quiet. The excited hum of voices before a highly anticipated Grand Rounds is notably absent. Teams who previously collaborated closely have grown accustomed to seeing one another virtually. Residents and faculty no longer stop in the hallways to catch up and discuss an interesting case.

“This entire thing has uprooted our lives and changed the way we do things,” says Arendt. For the most part, Minnesotans have maintained urgency around preventative COVID-19 measures, like wearing face masks indoors and social distancing. In the midst of flu season, however, COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations have exceeded springtime levels. While gathering restrictions were largely eased during the summer months, they were reinstated on November 13 to reduce spread and ease the burden on hospitals.

In lockstep, University President Joan Gabel extended remote work through June 30, 2021. While it’s unlikely things will return to pre-COVID normal anytime soon, and the U.S. healthcare system braces itself for what could be another surge in the coming months, there’s still work being done to move forward together. The department’s faculty, residents, and staff have demonstrated resilience, flexibility, and innovation solving complex problems over the last 10 months, and continue to advance the University’s land-grant mission.

“Organizations with a mission- driven culture have emerged from the COVID-19 pandemic stronger, and I’ve been more grateful than I’ve been in my career,” says Professor Peter Cole, MD, Regions’ chair of orthopedics. “Our department’s strength in the face of adversity promotes excellence. That’s been a great discovery.”