Cytogenetics Dramatically Expands its Diagnostic Reach

Cytogenetics, the study of chromosomes, was until recently often considered merely an “add-on” to diagnostic testing services. Today, cytogenetics is at the forefront of clinical care, providing results that are critical to diagnosis and therapy. One of the reasons is because new technologies have allowed cytogeneticists to close the information gap between pathogenic chromosomal abnormalities viewed through a microscope and pathogenic DNA sequences evaluated on the computer.

The University of Minnesota Medical Center offers a full-service cytogenetics laboratory. The laboratory is staffed full time during the week with services on the weekends enabling response to a particular medical emergency need a physician might have.

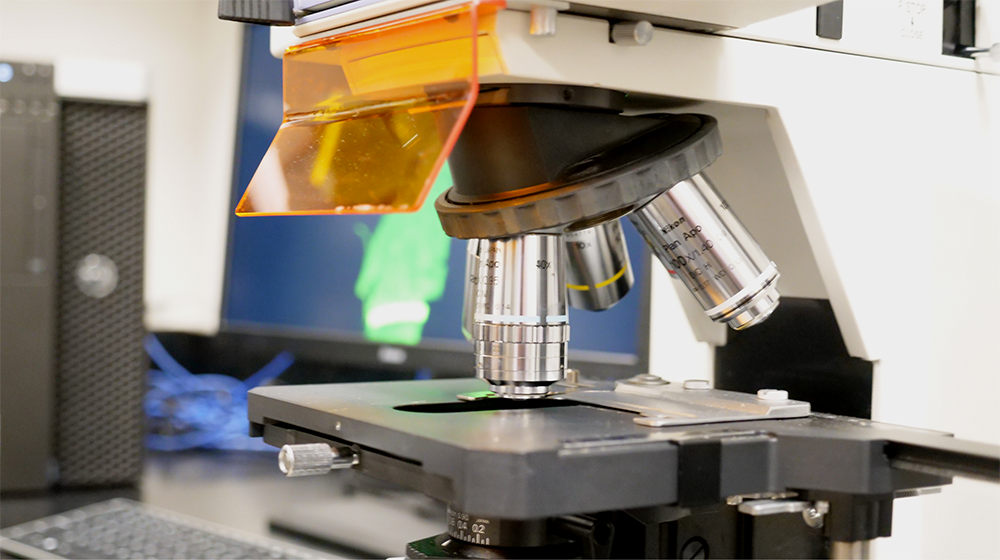

Laboratory senior director Betsy Hirsch, LMP professor, and co-directors Michelle Dolan, LMP associate professor, and Kelsey McIntyre, LMP assistant professor, oversee a laboratory with an expanding toolkit of cytogenetic and molecular cytogenetic techniques. According to Hirsch, these techniques allow them and their technical teams to identify chromosomal and molecular abnormalities that in congenital disorders are critical for diagnosis and for helping guide further medical work-up and genetic counseling. In cancer, they are critical for differential diagnosis, for helping guide therapy choices, and for monitoring residual disease following treatment. The techniques include standard G-banding of chromosomes, fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH), and chromosomal microarrays, a technology this laboratory introduced to the state’s cytogenetics community and one that is proving to be invaluable for identifying submicroscopic deletions and duplications that have diagnostic and prognostic importance.

“Our laboratory technologies have continued to develop over time and advance,” Hirsch said. “One of the things we really pride ourselves on is to be able to be relatively seamless as we move from one technology to another in an effort to help referring physicians and pathologists identify the best therapeutic approach.”

The Cytogenetics Laboratory has long had a strong focus on analyzing leukemias, lymphomas, and other hematologic malignancies. Hirsch plays a significant role in the Children’s Oncology Group (COG), a National Cancer Institute-supported clinical trials organization devoted exclusively to childhood and adolescent cancer research. As a pathologist, Dolan is particularly interested in solid tumors including breast cancer, and McIntyre is focused on connecting next generation sequencing data with cytogenetic data to capitalize on the unique strengths of these domains. All three directors are committed to education of practicing physicians, as well as medical students, graduate students, residents and fellows.

“As targeted molecular therapies get developed – therapies that target a specific genetic abnormality in the leukemic cells or solid-tumor cells -- it’s more important than ever to have diagnostic testing results immediately,” Hirsch said. For example, at the University, clinicians have established a new protocol for patients with acute myeloid leukemia, delaying initiation of therapy until they have laboratory results. Rapid genetic results are now a crucial component, together with the patient’s age and other clinical and pathologic findings, to the determination of therapy. In some cases, Hirsch and her colleagues recommend against additional testing depending on initial results. “The idea is to maximize the informativeness of the studies that we do and minimize the financial burden to the patient.”

Within the constitutional realm (conditions that individuals are born with), microarray techniques are proving to be particularly useful in the diagnosis of neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism. Microarray analysis shows that about 10 percent of patients with autism or unexplained neurodevelopmental issues have a microdeletion or microduplication that is the cause. “If you have a child who has autism and physically there are no other signs, that is unlikely to be a big piece of extra chromosome material because there would be so many genes there that you would have some other manifestations,” Hirsch said. Microarrays are able to identify the smaller submicroscopic alterations, and for these families, end the often difficult and extended diagnostic journeys. Similarly, there is an growing need for microarray testing with a very rapid turnaround for newborns in neonatal intensive care units who are born with significant cardiac, renal, or neurological conditions. Arrays can yield an answer in 48 hours. That answer not only impacts the treatment of that newborn, but in many cases, has implications for other family members and future family planning.

“I think the primary point I would emphasize is the importance of working collaboratively in partnership with the referring pathologists and treating physicians, as well as with other specialty laboratories such as hematopathology, flow cytometry, and molecular diagnostics.”

If you have questions about how to refer a consult to our University of Minnesota Physicians Outreach Laboratories or about pricing, contact Laura Funches at 612-625-3949 or at funches10@umphysicians.umn.edu.