Cancer Immunotherapy and the Art of Storytelling

Storytelling is at the heart of successful communication about scientific advances to the general public. That’s why Kiara Ellis and Chris Pennell begin and end their public presentations about the new cancer immunotherapies with the story of Emily Whitehead.

Ellis, manager in the Office of Community Engagement and Education (CEE) at the Masonic Cancer Center, and Pennell, LMP associate professor and CEE associate director, explain their public engagement efforts in “Demystifying cancer immunotherapy for lay audiences” published last October in the journal Frontiers in Immunology.

The paper is “the story we typically tell adult, lay audiences about cancer immunotherapy,” one example, they say, of how to explain a scientific advance with broad implications for the treatment of cancer now and into the future.

The National Cancer Institute defines immunotherapy as “A type of therapy that uses substances to stimulate or suppress the immune system to help the body fight cancer, infection, and other diseases.” Ellis and Pennell typically begin their cancer immunotherapy presentations by showing a picture taken in 2010 of five-year-old Emily Whitehead, the first pediatric patient treated with a type of immunotherapy called CAR-T (chimeric antigen receptor-transduced T-cells), which Pennell is actively researching. Some healthy white blood cells from patients with B-cell leukemia or lymphoma are removed and genetically reprogrammed to recognize and kill tumor cells. The population of engineered cells is expanded in the laboratory and then infused in the patient.

The story they tell starts nearly half a century before Emily was born. “We say that in 1960, Emily would have had a 10 percent chance of survival given her diagnosis of pre-B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. But thanks to 50 years of research, her prognosis in 2010 was much better as her chances of long-term survival were 85–90 percent,” Ellis and Pennell write. But Emily relapsed following standard therapy and was near death with treatment-resistant disease in 2012.

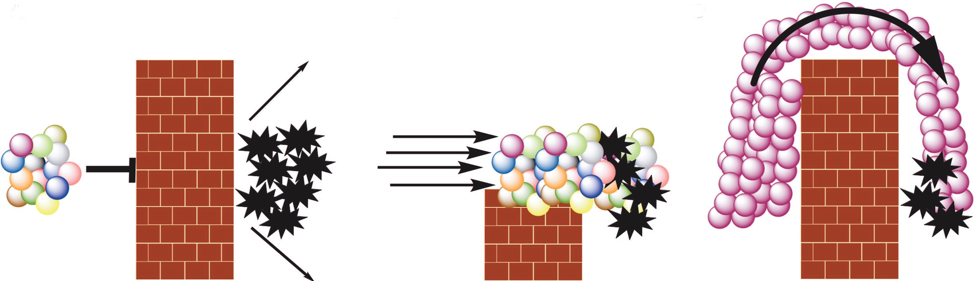

At this point, Ellis and Pennell break away from Emily’s story to describe their general approach to communicating cancer immunotherapies to a broad audience. There are sections about knowing your audience and strategies for engaging it, a primer on the basic biology of human immunity, an explanation of how cancer evades immune surveillance and spreads, and a description of two key cancer immunotherapies: Immune checkpoint blockades and CAR-T cells. The authors use colored spheres, black stars, brick walls to illustrate how cancer cells circumvent immune surveillance.

On the left, specialized immune cells (colored spheres) attempting to access tumor cells (black stars) encounter a barrier (brick wall) erected by tumor cells. In the middle, checkpoint blockade therapy inhibits the ability of cancer cells to erect the brick wall, permitting various types of lymphocytes to access and kill malignant cells. In CAR T-cell therapy, as illustrated on the right, white blood cells equipped with a specific homing molecule targeting specific cell-surface antigen on the cancer cells are expanded to large numbers in the laboratory and then infused into the patient. They surmount the tumor-erected barrier, access the cancer cells, lock on to them and kill them. This is how, in 2012, Emily Whitehead’s deadly, treatment-resistance leukemia was put into remission. A similar process has put the active leukemias of many other children into remission since Emily’s amazing response was first reported.

At the end of their public presentations on cancer immunotherapy, Ellis and Pennell “close the story loop” by showing a picture of a healthy Emily, now fourteen years old. They describe both the promise and the current limitations of immunotherapy, particularly CAR-T cell immunotherapy, and stress that it will take much more research to accomplish better outcomes with fewer side-effects.

Ellis and Pennell observe that, in many cultures, storytelling is the traditional method of teaching. “In the Hmong culture, skills, customs, historical knowledge, and traditions are passed orally from generation to generation via rote learning, memorizing, and storytelling,” they write in their conclusion. “Because humans are attuned to story-telling, we tell stories based on immunology and cancer immunotherapy that weave in facts with easily recognizable analogies.”

Communities share their concerns about cancer with Ellis and Pennell, enabling them as science communicators to partner with each community to address its specific needs. What they find most satisfying about their public engagement effort is the overwhelming and uniformly positive responses they have received. “Cancer adversely affects us all, either directly or indirectly,” Pennell said. “Most people want to know more about cancer: why it can be deadly, how to reduce the risk of getting it, and what to do if you do get cancer.” That means audiences are generally receptive to begin with, and they depart with “actionable knowledge” that Ellis and Pennell hope will help ease the burden of cancer on them and their loved ones.

Immunotherapies are a key component of the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Moonshot initiative. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved eight immune checkpoint blockade drugs and two CAR-T cell therapies since 2011. Some 320 clinical trials involving immune checkpoints or CAR-T cells are either recruiting patients (257), actively underway (44), or have been completed (21) in recent years.

The public face of science is something basic researchers like Pennell don't often see “even though ultimately it is the most important aspect of our work,” he said. The need for greater understanding of cancer immunotherapy, including among diverse ethnic groups, make it a safe bet Ellis and Pennell’s public storytelling will be in growing demand because the revolution in cancer therapy that immunotherapy represents is just beginning.