Convalescent plasma for treating COVID-19 patients gives Cohn a national profile

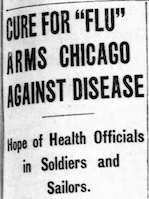

The influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 launched its deadly rampage across the American Midwest at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station near Chicago in September 1918. A month later the Chicago Tribune reported that the Illinois Influenza Advisory Commission was “roused to high enthusiasm” by a therapeutic breakthrough. “In a word, the treatment consists of the injection of a serum extracted from the blood of persons who have recovered from the influenza-pneumonia.”

The commission said it would try to secure a supply of the precious serum for local use in cases of severe illness by drawing on the graces of donor volunteers among the “jackies” at Great Lakes Naval Station and the soldiers at nearby Camp Grant, another infection hotspot. The commission stressed that the serum “is absolutely a different article from the vaccine which is to be manufactured under the commission’s direction after the method of Dr. E. C. Rosenow of the Mayo foundation,” according to the Tribune news account. “That vaccine is a preventive and is administered to persons who are well. The serum is a cure and is administered to sick persons.” In fact, the blood plasma of influenza survivors was not at all a “cure” for others who got infected, but a 2006 meta-analysis of clinical studies conducted at the time suggests that the neutralizing counterattack by plasma’s antibodies may have led to “a clinically important reduction in the risk for death.”

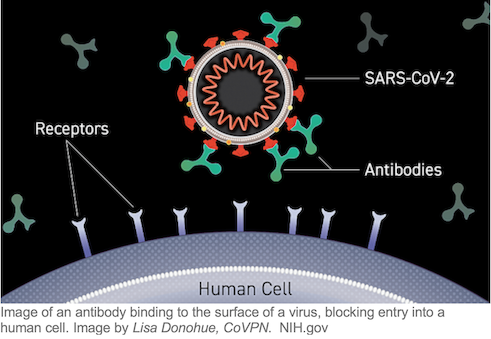

Today the antibodies in transfused convalescent plasma from individuals who have recovered from infection target the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in patients with COVID-19 disease. Laboratory Medicine and Pathology’s historic strength in transfusion medicine and blood banking has come into play in the pandemic crisis.

In her capacity as chief medical officer of the AABB (formerly American Association of Blood Banks), LMP associate professor Claudia Cohn has emerged as a national leader in explaining to journalists and the general public what convalescent plasma is, how it is collected, stored, and made available to hospitals, and the status of clinical trials that will reveal its ultimate place in the pandemic. Among her key colleagues is the Mayo Clinic’s Michael Joyner, who is heading a federally funded COVID-19 expanded access program set up to coordinate the collection and distribution of COVID-19 convalescent plasma across the country. More than 100,000 patients had signed up for the program and some 75,000 had been infused with convalescent plasma through August.

Convalescent plasma therapy is a type of passive immunotherapy. Passive immunotherapy has a long history of use against viral and bacterial diseases and remains the standard of care for treating diphtheria. Today, plasma-borne antibodies created by the immune system in response to attack by infectious pathogens are being brought to bear not only to treat the sick but also in an effort to help protect the vulnerable. Blood banks and collection centers plus plasma companies around the country store convalescent plasma for ready use, as do U.S. military bases, Navy ships on the seas, and federal stockpile freezers. As we will see, in an age of raging pandemic, blood plasma has become a strategic asset against the pervasiveness, relentless spread, worrisome physiological and mental aftereffects, and social systems wreckage of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus.

Convalescent plasma donation for COVID-19 patients

Claudia Cohn has been director of the University’s Blood Bank Laboratory since 2010 and associate director of Clinical Laboratories since 2016. Earlier this year she joined the Advisory Committee on Blood and Tissue Safety and Availability (ACBTSA), a federal advisory committee that provides advice to the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) through the Assistant Secretary for Health on a range of policy issues related to blood, blood products, and tissues. The committee is currently drafting a report that addresses issues surrounding the procurement, storage, and use of convalescent plasma.

Cohn joined Senator Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and health officials at M Health Fairview in Minneapolis July 18th in calling on the federal government to launch a nationwide effort to recruit plasma donors among people who have recovered from COVID-19. "Call Memorial Blood Centers, go online. Call the American Red Cross. Make an appointment to go donate your convalescent plasma. It takes less than two hours, usually about 90 minutes," Cohn said, according to MPR News. "And a single donation usually allows you to donate three units of convalescent plasma. That’s three lives you’ve potentially saved." Klobuchar and Senator Roger Wicker (R-MI) introduced legislation to raise awareness of plasma donation by amending Section 3226 of the CARES Act (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, March 2020) to include the reference “blood and plasma” (italics added) with respect to an HHS-directed national campaign to support blood donation.

“AABB is a big part of the convalescent plasma donation push,” Cohn said. “It helps coordinate the many different groups that are trying to get the word out – in particular the American Red Cross and American Blood Centers, the affiliation of independent blood centers. Both these organizations put out a strong plea for convalescent plasma and have tried to make it easy for patients to donate.”

Like donating blood, donating convalescent plasma is an act of volunteer altruism. It can’t be compelled, only encouraged. Under HHS Office of Civil Rights (OCR) guidance, health care providers are permitted to contact their patients who have recovered from COVID-19 to inform them about how they can donate their blood and plasma to help patients with COVID-19 without violating patient privacy under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). HIPAA permits health care providers to identify and contact recovered patients “for population-based activities relating to improving health, case management, or care coordination.” [OCR permission to contact recovered patients was extended to health plans in late August]. Unless patients give their consent, however, providers [and health plans] may not receive any payment from or on behalf of a blood and plasma donation center in exchange for such communications with recovered patients.

“There are some hospitals that have done a really nice job coordinating, getting the word out to their patients so that as patients leave the hospital they are contacted 14-30 days afterward (the period of time required to pass before donors can safely donate following a negative COVID-19 test) saying ‘Time to go give convalescent plasma if you’re feeling well,’” Cohn said. Some hospitals have in-house blood banks that direct their patient donors to collection centers upon discharge.

Convalescent plasma donations since the pandemic outbreak have waxed and waned. “There was an amazing initial spike of CP donations, largely in New York City and other cities along the Eastern seaboard that were hit first by COVID-19,” Cohn said. “There was a group that organized called Survivor Corps – 20,000 strong [115,000 by November] – and they were very active. At the time, the country had amassed some 30,000 excess plasma units in inventory, 9,000 of which were from the New York City area.” As of July more than 120,000 convalescent plasma units had been collected in total, she said.

Like blood donations following disasters, there was an initial large surge of convalescent plasma donation spurred by altruistic behavior among discharged COVID-19 patients, Cohn said. Recovered patients felt like they needed to give back. “I don’t know all the factors that are going into this but we currently are not seeing that surge anymore. The 30,000 excess plasma units in inventory have diminished to, say, a thousand units. Blood centers sent some of their units here to Minnesota, but lately a lot of their units have gone to Arizona, Florida, Texas [during summer outbreak] and other hotspots around the country.”

Cohn said AABB conducts a weekly survey to monitor convalescent plasma supplies nationwide. “We ask ‘Have you seen delays in obtaining convalescent plasma?’ In the beginning there were delays all over. Then we got to a good number to meet demand. Now that supplies are tight, in the hot spots there have been delays again.” Indeed, so tight that care providers are being been asked to reduce the standard-of-care treatment of two units to one unit. “The initial, wonderful spike in donations has dropped, and we need to stoke it again.”

Convalescent plasma in COVID-19 clinical trials

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published its guidance for investigational use of COVID-19 convalescent plasma last spring. An emergency use investigational new drug (IND) application allows a provider to apply for compassionate use in an individual patient with severe or immediately life-threatening COVID-19. Clinicians and institutions set about initiating randomized controlled clinical trials to establish the treatment’s safety and efficacy for COVID-19 patients.

“The initial response from the scientific community, especially the key institutions that are really used to designing and running randomized controlled trials, was that convalescent plasma should be made available only for people who were enrolled in the trial,” Cohn said. “The FDA began to approve these trials. If you were at an institution holding such a trial you contributed by sending patients to a blood center, the blood center would then send the convalescent plasma back to you.”

But limiting convalescent plasma to patients enrolled in research center-based trials proved to be too restrictive for a nationwide outbreak, Cohn said. “In response, the FDA said, okay, you can obtain convalescent plasma by emergency IND (eIND), and we will make it so that if you call in and order a unit by eIND, you’ll have it within 24 hours if the unit is available. As a result, the FDA was overwhelmed with phone calls. They had so many requests for eIND.” According to Cohn, it was then that the FDA contacted Mayo’s Joyner and asked him to design a program that would expand access under the agency’s Expanded Access pathway, which he did. “Basically it says: If you have COVID-19 and you’re sick enough to be an inpatient, you’re entitled to be treated unless under the age of 18. He made it very easy. All providers have to do is go to the Mayo expanded access program website, sign up, and they’re a member of the program.”

With the surge of patient enrollees, the Mayo program applied for Emergency Use Authorization (EUA), the next step in the FDA’s pre-approval process. EUA is qualified rather than full approval and one that requires evidence of safety and efficacy. Though not risk free, convalescent plasma has a long history of safe use but must also meet the FDA’s EUA “may be effective” standard. The FDA granted EUA status to convalescent plasma in late August, noting in the accompanying Clinical Memorandum: “There is no currently adequate, approved, and available alternative to CCP (convalescent plasma) for treating COVID-19.” The agency based its decision in part on a study of more than 35,000 of diverse adults hospitalized with severe or life-threatening COVID-19 to receive convalescent plasma who were enrolled in Mayo’s expanded access program [discontinued with the FDA's EUA]. The preliminary study, which was not peer-reviewed, found that antibody levels in the convalescent plasma infused and the timing of treatment had a statistically significant effect in lowering mortality. A peer-reviewed matched-control study of more than 300 Houston Methodist hospital system patients, also published in August, provided evidence that transfusing critically ill COVID-19 patients with high-antibody plasma early in their illness reduced the mortality rate.

For evidence of efficacy, Cohn said, there have been case series studies published and matched control studies published, but there were no data from double-blind randomized controlled study published at the time the FDA made its EUA decision, which led to widespread criticism of the agency. “Because the COVID-19 expanded access program has been so successful, the randomized controlled trials are not enrolling enough patients,” Cohn said, adding that the FDA’s emergency use authorization is likely to exacerbate the problem. “In New York City where a lot of these trials were centered, there are few patients willing to enroll. Wherever the trials are underway, ethically participants have to be told that convalescent plasma is available if they choose to leave the study,” Cohn said. Of the 10 randomized controlled studies in the U.S. currently listed at ClinicalTrials.gov, only one is coming close to meeting enrollment goals -- a Columbia University-based trial that is partnering with Brazil, she said.

The COVID-19 randomized controlled trials are looking at many different protocols and patient populations in the search for convalescent plasma efficacy data. “Some have patient cohorts with mild symptoms, others with moderate symptoms, and still others with severe symptoms,” Cohn said, noting the C3PO trial (Convalescent Plasma in Outpatients With COVID-19), now in phase 3, that’s looking at whether passive immunization can prevent progression from mild to severe/critical COVID-19 illness. There is also a phase 2 prophylactic trial involving participants at high risk of exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, such as health care workers and their families, who are given convalescent plasma to see if they are protected against infection.

As a result of the enrollment squeeze, efforts are underway to combine as many published studies as possible -- whether case series studies, matched control studies, or randomized control studies – analyzing the pooled data and looking to see if an informative signal emerges. Cohn herself has launched an effort to organize and analyze published data from disparate trials: “I’m leading a group that is taking all studies, making a grid of these studies – a matrix – and asking ‘Where are the apples-to-apples studies? Where are the apples-to-oranges studies?’ Wherever there are apples-to-apples studies, we’re reaching out to those conducting the studies and asking ‘Are you interested in joining forces?” She and her colleagues have succeeded in assembling a group of apples-to-apples studies and are currently analyzing their combined data.

The “gold standard” randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial rarely encounters pandemic disease in which urgency is manifest, survival may be at stake, and a potential therapy with a long history of safe use is available. Successful prospecting for clinical trials “gold” in the COVID-19 era means finding enough patients inclined to altruism who put top priority on what we can know.

Plasma goes strategic in an age of pandemic

Federal funding for Mayo’s expanded access program for convalescent plasma to fight COVID-19 was provided by HHS’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority. BARDA awarded the program $26 million in early May and subsequently added another $20 million.

Antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus have become a strategic, indeed a planetary resource as the pandemic sweeps across the globe. BARDA’S investment in antibodies as well as vaccines has no parallel. Patterned after the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), BARDA grew out of Project BioShield signed into law by President George W. Bush in 2004 to speed the development and stockpiling of vaccines and diagnostics to protect the U. S. from the worst consequences of a bioterrorist attack in the wake of 9/ll. As Leo Furcht and I wrote in our book The Stem Cell Dilemma (2008, 2011), then HHS Secretary Michael Levitt brought Project BioShield under the oversight of BARDA in 2007, stating that BARDA “enhances the opportunity for innovation in our efforts to develop effective medical countermeasures against a host of public health threats, either natural or manmade.”

BARDA manages pandemic stockpiles of bulk vaccine, adjuvant, plasma, or bulk intermediates for chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) threats, BARDA’s current acting director Gary Disbrow reported in 2016.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) stockpiles a number of vaccines and treatments for infectious disease including horse plasma-derived diphtheria antitoxin, a treatment pioneered by the German physiologist Emil von Behring, the “savior of children,” in 1894 for which von Behring was awarded the first Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1901. CDC’s supply of diphtheria antitoxin is made in Brazil, as the U.S. has no domestic manufacturers.

In addition to financing Mayo’s convalescent plasma national program, BARDA is giving $100 million to blood collectors to support their collection efforts, Cohn said. “In the past the collections were compensated only upon transfusion. Now they’re compensated upon collection,” Cohn said. “That shifts the dynamics. Blood collectors are now more invested in getting people out to donate.” Blood center and biomedical company executives gathered with President Trump and his key administration health agency heads and advisers at the American Red Cross Headquarters In Washington, DC on July 30th for a “Roundtable on Donating Plasma.” At the roundtable Trump announced that the federal government would provide “up to $270 million to the Red Cross and America’s Blood Centers for the collection of up to 360,000 units of plasma.” That many units could require as many as a million donations, according to Red Cross calculations reported in the Wall Street Journal.

Does the U.S. have the storage infrastructure for such a massive expansion of convalescent plasma units? “Collecting and stockpiling hundreds of thousands of units of convalescent plasma will be a major challenge, but that is the goal of the U.S. Government, so that if we have a reoccurrence, we have the materials available to deal with it,” Cohn said. Blood centers are already needing to make freezer-space room for the collections of both convalescent plasma and regular blood, she said. Space is at a premium. Moreover, fresh-frozen plasma has a shelf life of just one year, though Cohn imagines that could be extended and storage innovation advanced given the crisis.

BARDA is also paying tens of millions of dollars to private companies involved in developing hyperimmune globulin or polyclonal antibody immunotherapies by concentrating the antibodies present in convalescent plasma, which has been described as a polyclonal antibody “stew.” Every patient makes as assortment of slightly different antibodies in response to an infectious pathogen. Concentrating plasma antibodies makes for more effective therapy. “That’s why there is another push by the plasma industry -- the fractionaters -- to collect enough plasma to develop hyperimmune gamma globulin,” Cohn said. “Ten centers have organized to conduct a controlled randomized clinical trial of hyperimmune gamma globulin against COVID-19 to see if it works. Also, there are biotech companies making monoclonal antibodies.”

ClinicalTrials.gov lists some 40 studies involving monoclonal antibody treatment for COVID-19, the great majority of them recruiting patients. Monoclonal antibodies, generally expressed in the form of gamma globulin, are promising potential therapies and preventive agents because they can be specifically designed to recognize and bind to SARS-CoV-2 molecular targets, neutralizing the virus’s ability to enter cells. The convalescent plasma antibody “stew” can be screened for those antibodies that bind tightly to different parts of the virus’s receptor binding domain (RBD) on its spike protein coat. Convalescent antibodies with high-affinity RBD binding guide monoclonal antibody design including for an “antibody cocktail” that binds to a number of RBD molecular targets, an approach currently in late-stage clinical trials that BARDA is supporting to the tune of more than half a billion dollars. More than a dozen companies, some with federal funding, are currently developing monoclonal antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 based on unique antibodies identified in the plasma “stew.”

Yet of the 85 monoclonal antibody-based drugs the FDA has licensed for use since the first one was approved in 1986, only four are for treating infectious disease. As with convalescent plasma, patient enrollment in NIH-sponsored randomized controlled trials is taking longer than expected. Scaling up monoclonal antibody manufacturing to produce tens of millions of doses has never been done. Monoclonal antibodies are likely to be expensive compared to passive immunotherapies, placing them beyond the reach of many poor people and poor countries, and their protective or therapeutic benefit is likely to be measured in months. That is why they are often described as a “bridge” to a vaccine, a bridge whose blueprints draw design inspiration from blood plasma, an immunological wellspring. The FDA emergency use authorization prompted a response from the National COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma Project: “While not a panacea, convalescent plasma addresses a gap in therapeutic options that looms especially large until widespread vaccination can be achieved.”

Convalescent therapy and other passive immunotherapies, with their bounty of diverse antibodies, are almost certain to expand their pandemic province even as the drive for safe, effective, and universally available vaccines for COVID-19 picks up speed. We do not know how experimental vaccines will fare. We do know that convalescent plasma possesses therapeutic ingredients plus, thanks to the immune system’s abundant creativity, certain designs that give antibody engineers what NIAID director Anthony Fauci calls a “jump start.” Cohn and her transfusion medicine colleagues around the world labor in a well-functioning clinical arena with a solid foundation. That foundation was built more than a century ago by what is still regarded as one of the premier therapeutic innovations in public health.