Are people who have long-haul COVID more at risk for Alzheimer’s? University researchers looking for a possible connection.

French cognitive theorist Jean Piaget once said, “Scientific knowledge is in perpetual evolution; it finds itself changed from one day to the next.”

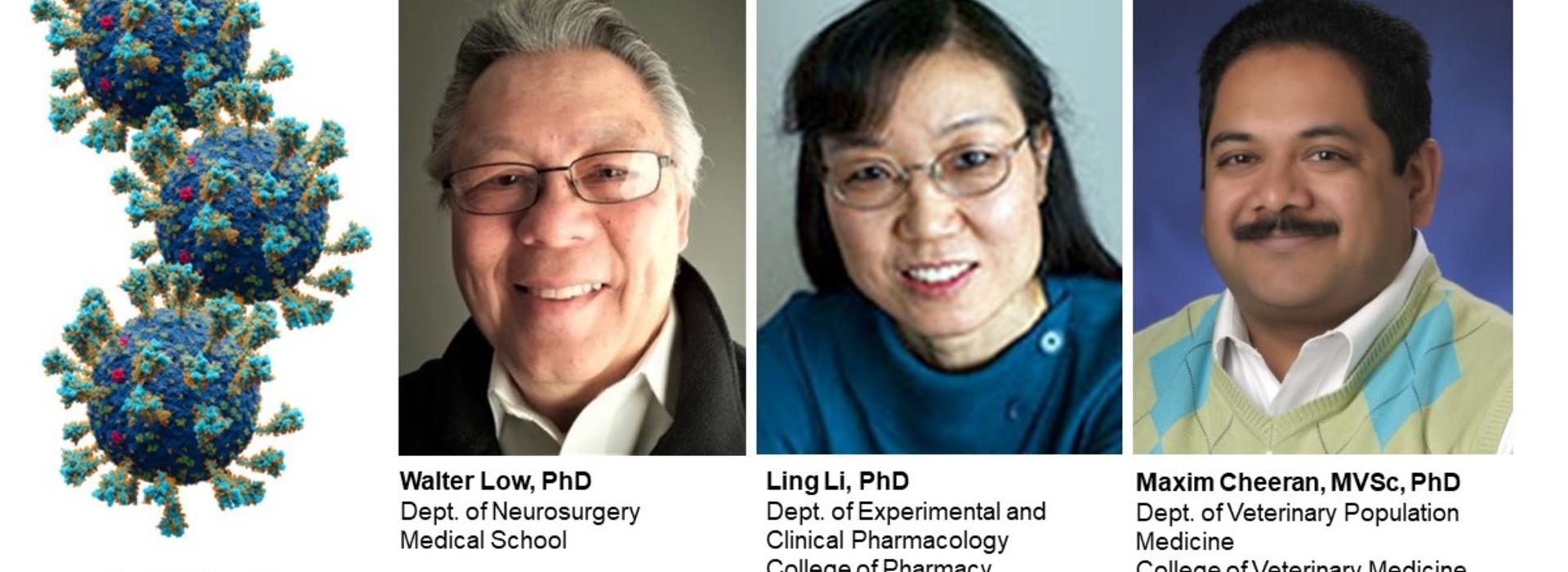

Department of Neurosurgery researcher Walt Low, PhD, believes firmly in that perpetual evolution. When the COVID-19 pandemic shut down many laboratories in 2020, the Low Lab stayed open and turned its attention to the virus causing all the problems. “We began looking at the clinical data being released, especially regarding people coming down with long-haul COVID,” said Low. “Some of those people have severe neurological symptoms. We began discussing these issues with Dr. Ling Li, in the College of Pharmacy, and Dr. Maxim Cheeran in the College of Veterinary Medicine.” Cheeran’s lab studies the impact of innate and adaptive immune responses on the outcomes associated with viral infections. Li studies the pathogenesis of lipid disorders and Alzheimer’s disease.

Genetic risk

It turns out that this subset of long-haul COVID sufferers often has a special genotype, according to Low. They have a gene known as APOE4, a variant of apolipoprotein that encodes proteins carrying cholesterol around the brain. “In the Alzheimer’s field, the highest risk for late-onset Alzheimer’s is having this gene,” said Low. “It made us realize that there might be an emerging problem here. In people with long-haul COVID, what if the viral particles remain and stimulate a pathophysiological process that ultimately leads to Alzheimer’s disease?”

A horrifying question. According to the Alzheimer’s Foundation, an estimated 6.5 million people in the United States, age 65 and older, are currently living with the disease. That’s not counting those with early-onset Alzheimer’s. In addition, a study published in February 2021 by the University of Washington in Seattle found that 32.7 percent of COVID-19 outpatients developed long-haul symptoms and 31.3 percent of hospitalized patients became long haulers. The condition is now considered a disability under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Latent viral component

“People who have looked at plaque entanglements in Alzheimer’s are finding a viral genome inside them,” noted Low. “There is an emerging hypothesis that Alzheimer’s disease has a latent viral component that is triggered later in life, much like how the latent chicken pox virus triggers shingles. That was the inspiration for us to think about COVID 19 and the onset of Alzheimer’s disease.”

Low, Li, and Cheeran applied for a five-year RO1 grant, which was awarded and then converted to an RF1 award by the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Aging. The grant is titled, “Acute and Long-Term Impact of SARS-CoV2 Infection and its Interaction with APOE on Cognitive Function and Neuropathology in Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease.” The unique thing about the award is that the first three years of funding are front-end loaded, according to Low. “After showing good progress, the fourth and fifth years of funding will come,” he noted.

This collaboration is representative of the interdisciplinary nature of today’s research. The project encompasses the Medical School, College of Pharmacy, and the College of Veterinary Medicine; and brings together the disciplines of neuroscience, pharmacology, virology, and bioinformatics.

Building on a foundation

This isn’t the first time that Low has investigated Alzheimer’s. “One of the earliest observations made about the disease was that an area of the brain that seems to be affected is the cholinergic nucleus basalis, clusters of neuronal cells that synthesize neurotransmitters known as acetylcholine,” he said. “We looked at the possibility of transplanting neural progenitor cells that develop into cholinergic neurons into rats who have lost their cholinergic input.”

Rats without that input can no longer navigate several different types of mazes. They can’t learn how to get from point A to B efficiently, according to Low. “We transplanted progenitor cells that produce acetylcholine into the hippocampus – an area known as the brain’s GPS system — in the brains of these rats,” he said. “What we found was that these animals could again navigate the mazes.”

APOE4 and COVID

In studying mice and their genotypes under the new NIH grant, the team discovered that the animals with APOE4 were more severely infected by the SARS-CoV2 virus. The APOE4 mice are also known for memory loss and their inability to navigate themselves from one point to another, which are key symptoms of people with Alzheimer's.

“We’ve been synthesizing all this previous information and seeing what correlations emerge that might give rise to new therapies … new associations that could lead to earlier onset of Alzheimer’s disease,” said Low. “Using these models, what are possible therapies we could generate and how could we correlate our findings with the impact of long-haul COVID? We want to identify the mechanisms by which COVID-19 could lead to Alzheimer’s disease and then develop new therapies that prevent it from happening. This could be done well in advance of a potential COVID-19-related epidemic of Alzheimer’s patients.”

One important piece of information the team needs is whether COVID patients are getting genetic screening. “Some are … that’s key,” said Low. “We’ll be interrogating COVID-19 databases to see if patients with the APOE4 genotype go on to have more severe neurological outcomes during long COVID.”

Meeting new challenges

Low’s ability to pivot to meet new investigational challenges such as the impact of COVID on Alzheimer’s disease is important to the “perpetual evolution” that Piaget described. “There will be opportunities for you and your lab to contribute even during the most adverse circumstances such as a global pandemic,” he said. “When people see a situation, they want to correct it through their own talent and experience. They will find ways to help.”

There are those who would argue that scientifically, people should stay focused in one area. “I’ve always been more collaborative and wanted to explore different ideas,” said Low. “For a younger investigator, it’s wiser to focus initially, which allows them to build expertise in a particular area. Academically, that stability in focus is important for them to get promoted and earn tenure. When you have tenure, it allows you to explore and to take greater risks. That’s where new discoveries can be made. Follow your interest, look at your bandwidth. If it can allow you to encompass a greater repertoire of skills, ideas, and projects, then do so.”