Injuries from Less-Lethal Weapons during the George Floyd Protests in Minneapolis

(NOTE: as protestors were injured and treated during the George Floyd protests in the Twin Cities, an interdisciplinary U of M team realized that not much research had been done on the impact of the "less lethal" weapons being used. This letter to the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine from the team summarizes their analysis of the injuries and suggests a new way forward.)

To the Editor:

On May 25, 2020, George Floyd died at the hands of police. Worldwide demonstrations against racial inequities ensued. In the face of a pandemic, the George Floyd protests had an estimated participation of more than 15 million people, making it one of the largest protests to date in the United States.1

Throughout these protests, law enforcement used less-lethal weapons as a method of crowd control despite evidence of associated injuries and death. Systematic reviews of cases in which patients were treated for injuries caused by these weapons have shown that 1.3% received permanently disabling injuries from chemical irritants and 15.5% received such injuries from projectiles.2,3 However, the majority of the studies were from outside the United States. Law enforcement in the United States has used less-lethal weapons for decades, but injury reports have only recently emerged.4 Therefore, we conducted a retrospective analysis involving patients injured by less-lethal weapons who were treated in two large Minnesota hospital systems during the George Floyd protests.

This retrospective study included patients of any age who underwent medical evaluation from May 26 to June 15, 2020 in primary care clinics, urgent care clinics, and emergency departments in two medical systems in Minnesota and who had International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, codes S00 through T59 (indicating consequences of external causes and injury diagnoses) or who had “riot,” “rubber bullet,” “tear gas,” “protest,” or “projectile” in the notes in their electronic medical records. We excluded patients who had not sustained an injury, who had injuries that did not relate to protests, or who had injuries that did not relate to less-lethal weapons or officer violence. (Details are provided in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org.)

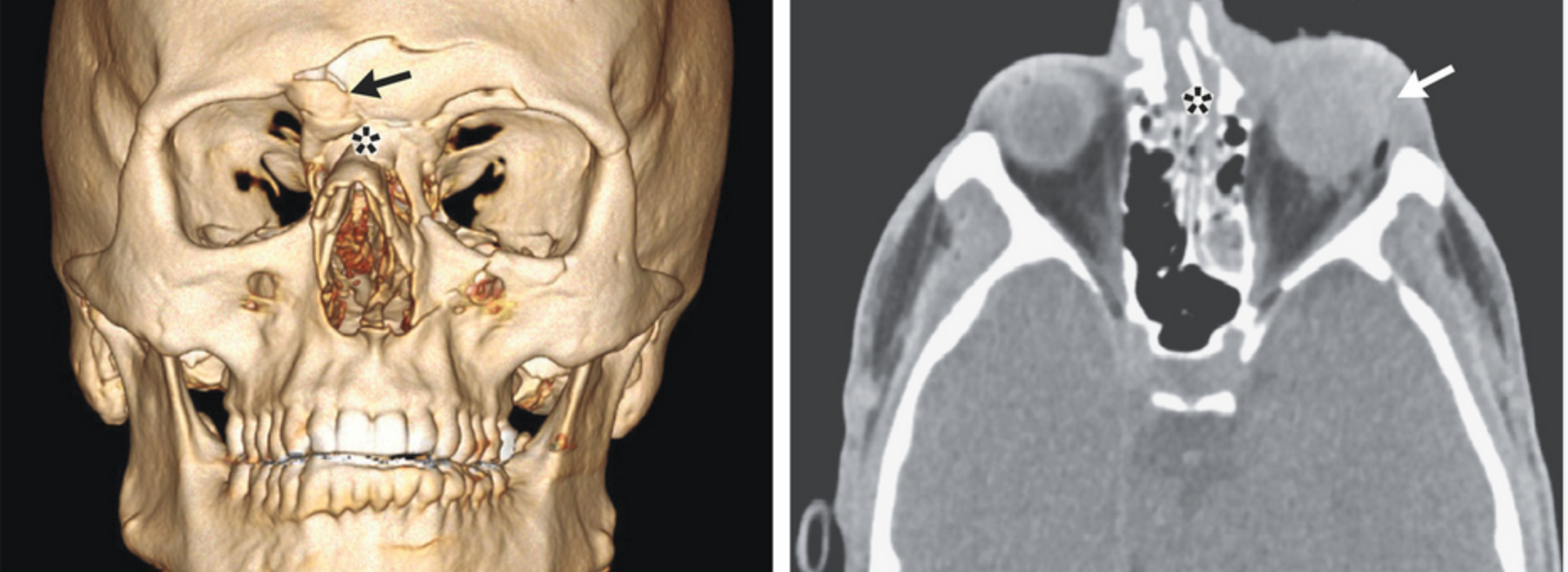

Figure 1. Patient with a Penetrating Injury to the Left Eye.

Of the 6626 medical records identified during the initial search, 89 met the study criteria, with 45 (51%) indicating injuries from projectiles, 32 (36%) injuries from chemical irritants, and 12 (13%) injuries from both types of weapons. Patients reported 41 injuries from rubber bullets, 7 from tear gas canisters, 2 from beanbags, and 7 from unknown projectiles. Ten patients (11%) sustained eye trauma from projectiles (Figure 1). Seven patients (8%) underwent surgery for their injuries, and 16 patients (18%) had received traumatic brain injuries. A substantial percentage of projectile injuries were to the head, neck, or face (in 23 of 57 patients [40%]). The Injury Severity Score was used to classify the severity of trauma; the injuries were classified as mild in 77 patients (87%), as moderate in 8 (9%), and as severe in 4 (4%). However, these findings are not representative of everyone injured, because our sample was limited to persons who chose to seek medical evaluation.

Although less-lethal weapons are designed as an alternative to lethal weapons, we found a substantial number of patients with serious injuries, including many injuries to the head, neck, and face. United Nations guidelines state that these weapons should only be aimed directly at the extremities and that hits to the head, neck, and face are potentially unlawful.5 Although the results represent only a single region in a worldwide protest, these findings reveal that under current practices, projectiles are not appropriate for crowd control.

Erika A. Kaske, B.S.

Samuel W. Cramer, M.D., Ph.D.

Isabela Pena Pino, M.D.

Truong H. Do, M.D.

Bryan M. Ladd, M.D.

University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, MN

Dylan T. Sturtevant, B.S.

Aliya Ahmadi, B.A.

Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis, MN

Birra Taha, M.D.

David Freeman, M.D., Ph.D.

University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, MN

Joel T. Wu, J.D.

University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Minneapolis, MN

Brooke A. Cunningham, M.D., Ph.D.

University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, MN

Rachel R. Hardeman, Ph.D.

University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Minneapolis, MN

David J. Satin, M.D.

David P. Darrow, M.D.

University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, MN

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org.

This letter was published on January 13, 2021, at NEJM.org.

Ms. Kaske and Dr. Cramer contributed equally to this letter.