Pandemic response has been a roller coaster ride for Department providers and learners

When it became apparent in March of 2020 that the COVID-19 virus was at the pandemic stage, the University of Minnesota – and the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences – had to respond quickly and appropriately to safeguard its learners, faculty, staff, and on the clinical side, its patients.

As a result, the Department’s Education Team was one of the first in the nation to develop the policies and procedures – and the online curriculum – that would enable the switch to remote learning. And the Clinical Team helped usher in the almost complete switch to telehealth for its patients who had access to the appropriate technology (i.e., smart phone or computer).

It was like going over the first dip in a roller coaster.

Working from home

“Suddenly, we were at home engaging with almost all aspects of our work over the Zoom video platform,” said Assistant Professor Quentin Gabor, MD, Psychiatric Lead for the Community-University Health Care Center (CUHCC) in Minneapolis, MN. “We all felt a tremendous amount of distress on so many levels. We were worried about our patients, our colleagues and learners, our families, and about our own wellbeing. It was like a bad dream.”

Second-year psychiatry resident, Jon Swan (pictured), DO, spent most of his first year in residency (2020-2021) basically hunkering down at home. “We hadn’t set foot in the psychiatric inpatient unit since our residency interviews the prior fall,” he said. “For the first eight months, we were completely remote. We were the first program in the country to take that route and were also the first to have medical students rotate remotely on the unit.”

On the front lines

Although flipping the switch to remote learning and telehealth for patient care happened fairly quickly, getting there took some doing. For fourth-year resident Richard Coffin, MD, 2020-2021 was his clinical operations year and his third year in residency. That meant he was at the front lines of ensuring that the clinical practices put in place for the pandemic were effective and safe.

“The waiting room size was a significant barrier, as new patients still had to be evaluated in person and it was difficult to accommodate the six feet needed for social distancing,” Coffin said. “In addition, we required that residents wear face shields, masks, and gloves during in-person exams, and to wipe down every surface a patient may have touched following an appointment. Patients were also required to wear a mask.” Many of those requirements are still in place but they were new at the time.

Able to adapt

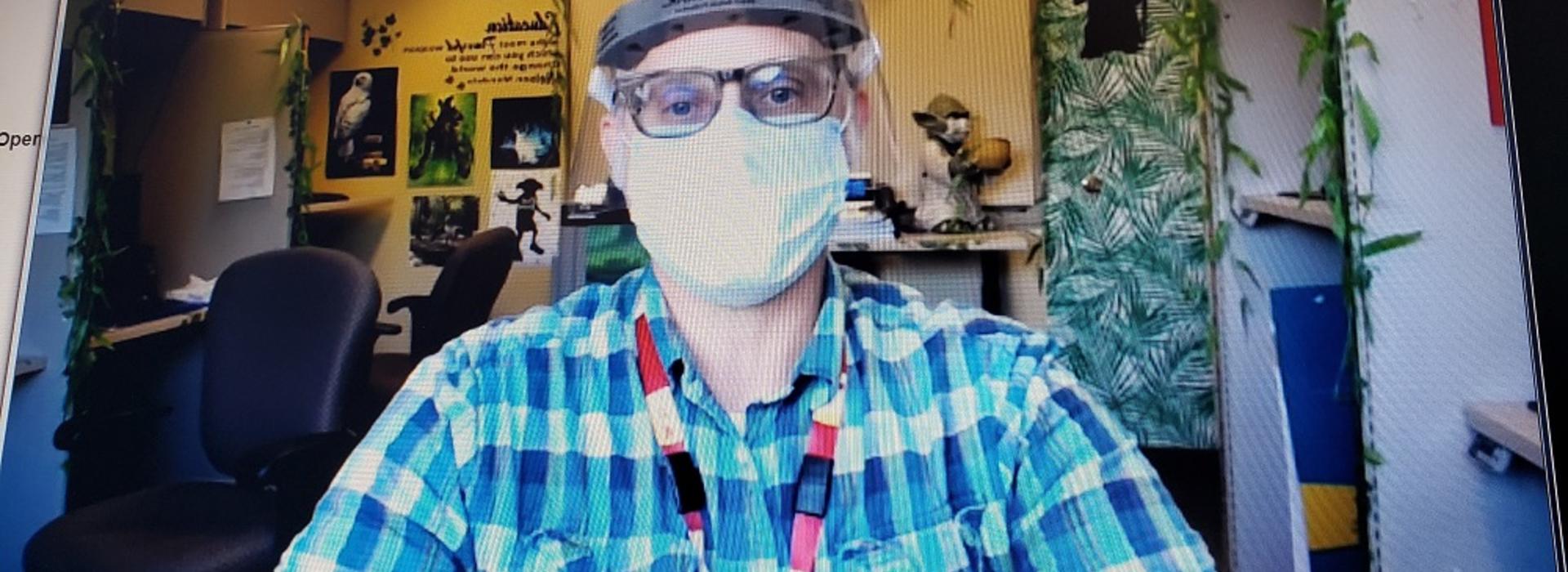

“We have had to be more flexible, never knowing what’s going to happen with COVID,” said Coffin (pictured). “All of this has shown some of the program’s vulnerabilities, which were primarily related to communication because we work with so many different institutions. We have also shown an excellent ability to adapt to different situations and big changes.”

Gabor felt that people continued to do their work without missing a beat. “I was impressed by how nimble the residents were in addressing their work via remote communication,” he said. Nimble they were, but they also felt isolated. “Getting a sense of community with fellow residents, faculty, and leadership was challenging,” said Swan. “When a Zoom ‘happy hour’ was proposed, people were just so tired of being on Zoom all day, even though we craved interaction, that no one wanted to attend.”

Added depth to relationships

Interesting things happened as a result of all the remote work. “There were some downright embarrassing noises from our animals and other family members,” said Gabor. “It became one of the strengths of using the remote medium because we got to see our patients in their homes, sometimes meeting family members who hadn’t been able to attend appointments with them, meeting their pets, seeing where they live. We were also meeting with residents in their homes. It all added depth to our relationships.”

There were the inevitable disadvantages of working remotely. “I want a tee shirt that says: ‘Technology: sometimes it works,’” said Gabor. “Even the most technology-savvy individuals ran into problems with their devices.”

While patients were more likely to keep their appointments if they were having them via their phone or computer, there were some issues. “Unfortunately, a big part of our job is doing mental status exams, which involves looking for abnormal, involuntary tics and watching someone speak and move,” said Swan. “If the exam is being done by phone or computer, we can’t really see if our patients are having side effects from their medications.”

Telehealth should continue

Despite this drawback, Swan believes that having mental health appointments via telehealth should continue for those patients who prefer it. “It’s extremely important to give people who are having a mental health crisis access to telehealth,” he said. “This is especially important for people with certain types of anxiety or phobias related to leaving their houses or being in new places.”

Gabor (pictured) agrees. “At CUHCC, I was pleasantly surprised by how quickly the medical providers and the patients and their families went with telehealth,” he said. “Everyone was thankful we could approximate a comprehensive visit via phone or video, although the vast majority of our visits were by phone. For decades, psychiatrists have managed psychiatric crises via the phone. After all, our work is mostly language based.”

That doesn’t mean he didn’t see disadvantages in working with most of his patients via the phone. “When a patient starts telehealth after having established a relationship with a provider, the transition is easier,” he said. “If the relationship is just beginning, it can slow the process of getting to know each other. And if your patient has to use the phone instead of a computer, you just can’t connect in the same way.”

Back to on-site and in-person

In July 2021, patients slowly began coming back to in-person visits in the clinic. The beginning of Fall would see the learners coming back to campus. “It had been 500 days since the U had transitioned,” said Gabor. “It was like the springtime after winter.”

Residents have largely responded positively to being able to see patients in person, according to Coffin. “Some went from seeing all of their patients virtually to seeing them in clinic,” he said.

Constantly re-orienting

Swan noted that he and his co-residents have become comfortable with constantly re-orienting. “When we had our first in-person meetings, we weren’t always sure where the conference rooms were,” he said. “People had code words for them. They told us, ‘Go to this person’s room,’ and we would ask, ‘Where is that?’ We learned to rely on each other to navigate our changing environment – all of this has made us closer as a cohort.”

The residents had all these new layers of things they needed to learn. “One of the hardest things is that there wasn’t a lot of knowledge from anybody – everyone went through this at the same time,” said Coffin. “We couldn’t depend on the fact that we’ve been through this before, here are the issues we will run into, and this is how we will have to adapt.”

“It was energizing”

Although sad that he had to leave the daily routine he established with his family during the height of the pandemic, Gabor is glad to see his work return to on-site and in-person. “There was jubilation when we all sat down together,” he said. “It was energizing. For the residents who started this year in the outpatient clinic, it was comforting to have something be more normal after a bonkers year and a half.”

While Swan felt cautious about returning to campus, he noted that, “Our first year was a good run for whatever will happen during this pandemic. If we have to go back to a harsher lockdown again, we can do it because we’ve already done it. And we can still give quality care and feel a sense of togetherness.”

The Department’s experience with and response to the pandemic didn’t just affect the residents. “Many of us on the faculty feel that if we had started our careers when our 2020 residents did, we wouldn’t have managed as well as they have,” said Gabor. “We want to continue making their experience as profoundly positive as possible.”