Study evaluates time-tested neurostimulation technique for use in treatment-resistant depression

Clinicians have been stimulating the vagus nerve to treat epilepsy symptoms since the procedure received FDA approval in 1997. In 2005, the agency approved the use of an implanted vagus nerve stimulator for treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Even though approved for this use, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) has deemed it experimental and would not pay for the procedure. Insurers have followed CMS’ lead.

Re-vitalized industry interest in demonstrating the “non-experimental” nature of vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for treating TRD has resulted in an unusual CMS/industry-funded multicenter study known as RECOVER. The University of Minnesota is one of almost 60 sites throughout the country helping implant vagus nerve stimulators in 1,100 study participants to ascertain its long-term clinical efficacy in treating refractory depression.

Psychiatry/Neurosurgery collaboration

Psychiatrist Ziad Nahas, MD, MSCR, of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, is the principal investigator (PI) for the U’s portion of the study. Neurosurgeons Michael C. Park, MD, PhD; Robert McGovern, MD; and David Darrow, MD, MPH, of the Neurosurgery Department, are implanting the vagus nerve stimulators.

“We have slowly begun to partner with psychiatry using deep brain stimulation and vagus nerve stimulation to treat psychiatric conditions like depression and OCD,” said Park (pictured at left). “Psychiatrists are open to the idea of neuromodulation. The attractive feature is that you can turn the stimulation on and off.”

A little hint

A hotel employee helped scientists make the link between vagus nerve stimulation and mood improvement, noted Nahas. “When they were first working with epilepsy patients, a concierge of a hotel near where the study was being performed told one of the investigators, ‘I don’t know what you’re doing with these patients, but they look happier,’” Nahas said. “Those involved with the study started exploring its impact on participants and discovered that patient mood was improving independent of their seizure control. That was the hint that drove further exploration.”

Professor Thomas Henry, MD, of the U’s Neurology Department wrote a seminal paper about a PET (positron emission tomography) study that showed VNS was modulating not only the areas for epileptic seizure control but also the limbic area, according to Nahas. That led to the first VNS for depression study at four U.S. sites. “The first patient ever implanted was in my lab at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston,” he noted.

Follow the network

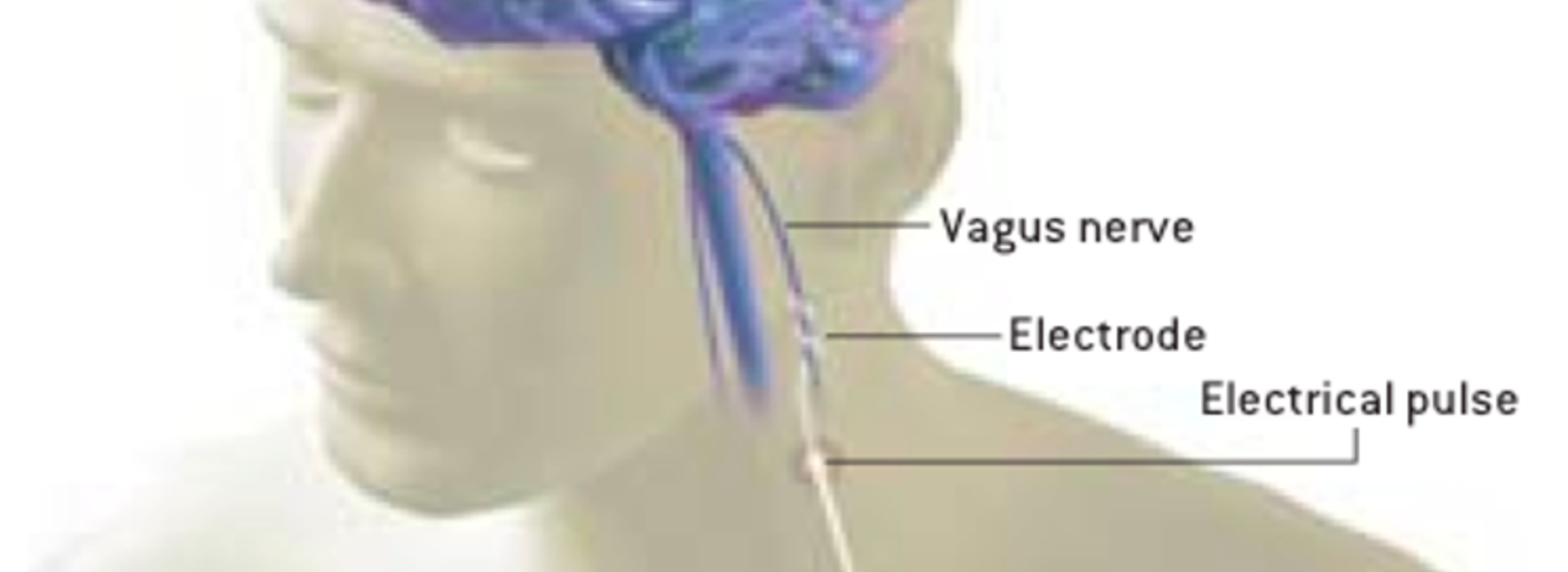

According to Nahas (pictured at left), 80 percent of the fibers in the vagus nerve carry information from the body to the brain. “One of the first ‘bus stops’ along the way to the mid brain is a critical node involved with depression,” he said. “If you follow the network of modulated brain activity through the vagus nerve, a lot of it is in limbic and frontal areas of the brain, key regions for regulating mood.

“We know that by tickling the vagus nerve with electrical pulses, we are modulating brain networks critical for mood regulation,” Nahas continued. “As you stimulate day and night over several weeks, the brain activity adapts and starts mimicking the effects we see with other antidepressants. The unique difference, however, is that while changes are much slower, they confer longer-lasting positive effects and protection against relapse.”

Could double your chance of getting better

Unfortunately, the placebo control arm of that initial study failed to capture the slowness of the effect as it takes months for VNS stimulation to have a discernible impact on depressive symptoms. “The long-term data, however, was impressive enough to convince the FDA to approve the treatment,” said Nahas. “At one year after implantation, we’ve seen that VNS doubles TRD patients’ chances of getting better. That, to me, is what is fascinating about vagus nerve stimulation. In the long run, it seems to alter the course of some patients’ illness.”

Treatment-resistant depression (TRD) is defined as major depressive disorder (MDD) in adults who have not responded to at least two different antidepressant treatments in a current and chronic severe depressive episode. Treatment resistance can occur in up to 30 percent of the treated MDD patient population. They have limited options. “They have failed everything,” said Darrow (pictured at left). “This will hopefully provide one more possible treatment that could help them with their recovery.”

Study participant requirements

To be in the study, you must be a Medicare beneficiary, at least 18 years old, currently depressed, and have depression or bipolar depression that has lasted for at least two years or recurred several times. Furthermore, the definition of TRD for study participants is more stringent. You must also have tried at least four treatments and not found them helpful.

“The study will eliminate those with a history of psychosis,” said Nahas. “You also cannot have a comorbidity, such as OCD, that is a primary diagnosis.” Any medication that study participants are currently on must not change for a year.

The study is blinded and randomized. “For the first year, not everyone will be exposed to the stimulation,” explained Darrow. “After that, all participants can benefit from it.”

The U of M neurosurgical team has already implanted six patients. “It’s an interesting surgery because the vagus nerve is pretty small and sits between the carotid artery and the jugular vein,” said Darrow. “During the procedure, we wrap the nerve with three helical electrodes.” Because the stimulation is selective – running for short periods during the day – the most common thing that people notice during stimulation cycles is that they may have a tickle in their throat, or their voice may become hoarse. “That’s because the vagus nerve innervates the vocal cords,” Darrow said.

Study add-on

The interventional psychiatry program will do the initial detailed assessment, track participants’ progress, and adjust the stimulation as needed. Nahas is hoping to include researchers Kelvin Lim, MD; and Bryon Mueller, PhD; from the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences in the study. “We will do add-on imaging to help us understand both the predictors of response – is a brain pattern more likely to benefit from VNS – and to help track participants over time to see how their brain activity changes,” explained Nahas. The research team is applying to the National Institutes of Health for a grant to fund this aspect of the study.