Novel “high-fidelity” psychiatric simulation provides real-life experience for residents

Earlier this spring, first- and second-year psychiatry residents participated in a first-ever simulation experience. The effort was led by PGY-2 resident Jeremiah Atkinson, MD, and assistant professor Lora Wichser, MD (both pictured here). They applied for and were awarded a grant that funded their project in April 2021.

The grant was from the University of Minnesota M Simulation Award Program for Medical Education Innovation. The program is designed to advance training for medical students, residents, and fellows using simulation methodology. Little did Atkinson know that it would take two years to get the educational simulation project off the ground. Like everything else, COVID’s impact on clinical education caused difficulties with planning and scheduling. Despite the barriers, Atkinson and Wichser soldiered on and were eventually able to premiere their simulation on March 30, 2023.

Somewhat surprisingly, simulation hadn’t been used before in the U’s psychiatry residency. Because of that lack of direct experience, Atkinson did a literature review to find examples of psychiatric simulations that could be modeled. “We wanted to practice something that’s difficult to do,” he said. “In psychiatry, we have intense situations that can arise with our patients, though not consistently enough to have attendings model appropriate management. The first time I put a patient on an involuntary hold, for example, I was on call and the patient was very upset. I didn’t know how best to manage the situation, and wished I’d had experience before navigating that scenario with a real patient.”

Wichser and Atkinson worked with the M Simulation team, including executive director Lou Clark, PhD, MFA, and education director Anne Woll, MS, to write a novel script focusing on a situation that was like the one Atkinson had faced.

The simulation they created has four parts:

- The evaluation: this is an emergency psychiatric evaluation during which the resident says to the patient, “I’ve heard you want to leave the hospital, however, because you’re on the locked psych unit, the psychiatrist must evaluate you prior to discharge.” The residents must determine what brought the patient to the hospital, what’s going on with them now, whether they are able to make informed decisions consistent with their beliefs, and if it’s safe for them to leave.

-

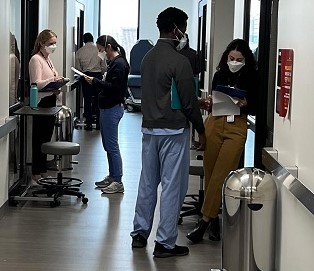

The presentation: a formal presentation of the patient to a supervisor. “You take all the information you gathered in the 20 to 40 minutes of patient evaluation and synthesize it down to the pertinent facts that are helping you make the decision,” said Atkinson. “Here is the decision I’m making and why and what must happen next. Crafting a good presentation is an essential communication skill that requires practice.” (Residents are pictured here going through that step with one another during the simulation.)

- The collaboration: going through the evaluation and recommendations with the inter-professional team. “That’s important because we don’t work in a vacuum,” explained Atkinson. “We need to be able to solicit concerns from our colleagues and work with them to make the safest decisions for our patients and ourselves. The first time I did this, for example, I didn’t know the questions I should be asking the nursing staff.”

- The explanation: learner returns to the patient to let them know that they’re being placed on a hold and why and describes some of the next steps. “We have to manage the patient’s anger, frustration, and posturing as they try to get what they think they need,” said Atkinson. “The simulation enables you to understand how to help the patient come to grips with what’s happening, using other staff to assist you.”

Atkinson believes their simulation is novel because he didn’t see any others during the literature review that had similar depth and structure.

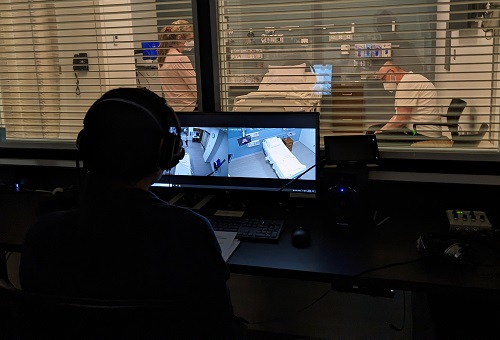

While the simulation can be run pretty much anywhere, doing it in the simulation center at the U had several advantages, according to Atkinson. “They have rooms they could configure to look like our psych unit,” he said. “They also have recording devices that enable other learners and supervisors to watch the simulation. There is so much happening during the actual process that you can’t reflect on things in the moment. Being able to review it afterwards is a huge benefit.”

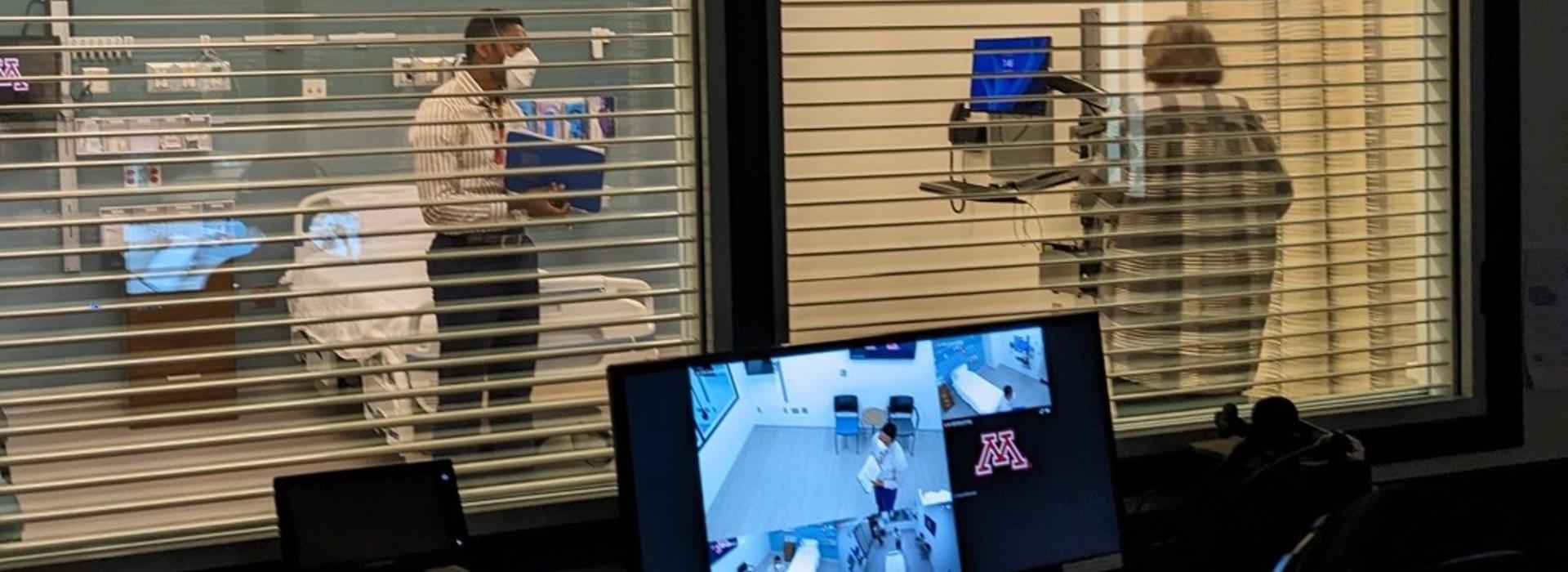

M Simulation also hired what’s known as “standardized” patients – trained actors who have read the script, know the cues and the backstory so they can embody the role. “All this makes it a high-fidelity experience, as close to real-life as possible, which creates a better learning experience,” said Atkinson. (PGY2 resident Caitlin Raasch, MD, is seen here working with a "patient" in the simulation. In the photo at the top of the article, PGY2 resident Christian Morfaw, MD, is doing the same.)

The learners completed the simulation in pairs. “The more experienced residents went through it first,” said Atkinson. “Everyone was reassured that it wasn’t a graded evaluation, it’s a formative experience.”

Residents had positive reactions to the simulation. Comments from the post-survey included:

- “It was a great opportunity to practice real-feeling, difficult encounters.”

- “Appreciated getting feedback from co-residents.”

- The simulation, “Foster[ed] a nonjudgmental environment to give and receive feedback, especially from the standardized patients themselves, which almost never happens in the clinical setting.”

Participants asked to make this an annual event to help prepare them for similarly difficult clinical scenarios, according to Atkinson. “The whole point of simulation is to help provide safer, better patient care,” he said. “I think it’s worth the investment.”