Faculty member finds that working in an area that helps kids with FASDs is “pretty powerful”

Up to 1 out of 20 – or around 5 percent – of children in the United States has one of the Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASDs) because alcohol was consumed at a binge level (4 to 5 drinks in an episode) during a pregnancy. “In animal models, even low levels of alcohol exposure can affect fetal development,” said Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Professor Jeffrey Wozniak (pictured above during a local TV interview), PhD, LP, an expert on FASDs. “It depends on many factors such as timing of the drinking, genetics of the mother and fetus, as well as the mother’s age, general health, and nutritional status. That’s why we say there isn’t a safe level of alcohol exposure – nearly all the world’s public health agencies recommend no alcohol exposure at all during pregnancy.”

Wide range of effects

FASDs can have a wide range of effects on children. “In some cases, there are profound impacts on IQ and physical development,” said Wozniak. “These individuals can have other physical manifestations such as facial effects and impacts on additional organ systems.” Cognitive and behavioral issues are very frequently observed following prenatal alcohol exposure.

It’s never too late to identify children with FASDs and start interventions, according to Wozniak. “The children most severely affected are easiest to identify and diagnose,” he noted. “In our clinic and around Minnesota, we often see these kids first between the ages of 2 and 6. They come to our attention most often in preschool and during early school ages.”

Improving outcomes

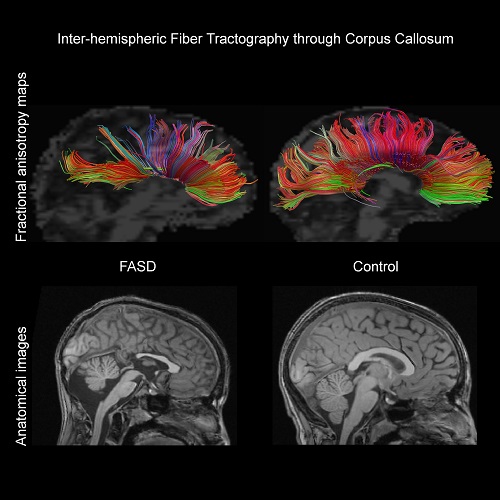

Wozniak (pictured here) is determined to improve the outcomes for children with FASDs. “During the first 10 years of my research, I was focused on understanding what happens in the brain because of prenatal alcohol exposure and how it affects cognitive ability – such as memory, learning, and attention,” he said. “We have since moved into investigating a nutritional intervention in very young kids when it can still help the developing brain. There are hardly any interventions that have been tested … only a handful of groups are doing it. It's a smaller area of research because intervention research for neurodevelopmental disorders is rather difficult.”

It's a challenge to design a neurodevelopmental study so that you’ll be able to measure a treatment’s effect, according to Wozniak. “Trials of this sort are time-consuming, especially when you’re talking about young children,” he said. “We must follow them for years at a time. During one study, we followed up four to five years afterwards to measure the developmental outcomes.” There are also practical challenges and regulatory burden with human intervention studies. “You have to find, enroll, and keep subjects in the study,” said Wozniak. “It takes a lot of staff energy and time and a lot of commitment on the part of the families.”

Next phase of research

His team is beginning the next phase of their work and just received a favorable score on a National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) grant for a new investigation that they hope to start in June. This new project is part of the work Wozniak and his team are doing with an international group called the Collaborative Initiative on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Disorders (CIFASD) under the auspices of the NIAAA. The Collaborative is studying FASDs from multiple perspectives (genetic, embryological, brain, cognition, prevention).

“CIFASD has brought together researchers at the basic science level who are studying genetics in zebrafish and rodents and learning how alcohol affects the development of an organism at a very basic level,” Wozniak explained. “I’m working with other researchers studying children and working with their parents. Bringing all these specialties together and having them interact and share data is a unique and powerful way to push our knowledge forward. We learn from each other at all these different levels of science.” For instance, what the scientists learn from a genetic study helps other researchers understand where they should be looking in the brain for the effects of alcohol.

U of M collaborations

At the local level, Wozniak’s team works with the Pediatrics Department and its FASD Clinic and Adoption Medicine Program, under the leadership of Amy Gross, PhD, LP, BCBA, Amanda Kalstabakken, PhD, LP, and Judith Eckerle, MD. “In Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, we work with Dr. Kelvin Lim and Dr. Bryon Mueller and others on neuroimaging and brain stimulation,” said Wozniak. “We also have image analysis experts, statisticians, and pharmacists involved.”

As they continue to work both locally and with CIFASD, the next phase of research for Wozniak’s team is an exciting one filled with potential. “We know that cognitive training – practicing attention and memory tasks – can help kids with FASDs develop those stills, but it’s limited,” he said. “It takes a lot of attention and repetitive effort, and the effects don’t stick as much as you’d like them to.” His team believes that adding brain stimulation using transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) helps maintain the effects of cognitive training longer. “It could also help generalize the effects to other areas of cognition,” Wozniak noted. “If you’re doing the brain stimulation while you’re also doing an important task such as cognitive training, the literature suggests that it helps sustain the benefits of it.”

Firing up neurons

During the stimulation, the subject wears an electrode-studded skull cap that provides low levels of electrical current. “It stimulates a couple of millimeters into the cortex of the brain,” said Wozniak. “It causes the neurons to be slightly more likely to fire and make a new connection or synapse. If you’re stimulating across a part of the brain that you want to influence and you’re doing cognitive training at the same time, firing neurons in that area, the combination causes the effects to be slightly more likely to stick.”

One of the challenges in working with children who have FASDs is the general public’s understanding and willingness to accept that alcohol is dangerous during pregnancy. “After 50 years of research and clear understanding of the biology, there is still misunderstanding in the general public and the media,” said Wozniak. “Some of it is simply avoidance or skewing of facts and some of it is proliferation of bad information.”

Overcoming misinformation

Minnesota is working to overcome that misinformation through an organization called the Proof Alliance. “They educate professionals around the state, including doctors, mental health providers, social workers, and people doing foster care,” said Wozniak. “We help each other disseminate information throughout the state to people who need to have access to it.” Proof Alliance also holds workshops and conferences and places ads to create public awareness. “They help spread the messages from all this research and are a national leader themselves in innovative FASD programming,” Wozniak added.

The work he does on improving outcomes for kids with FASDs is very rewarding. “Any child has developmental potential, no matter what’s occurred,” said Wozniak. “We know that alcohol has bad effects but that doesn’t mean we can’t leverage all the power of the child’s development to come. The more we can reach kids, the more creative we can be with our research efforts. We can actually influence outcomes for them and that’s pretty powerful as a researcher.”

Learn more: