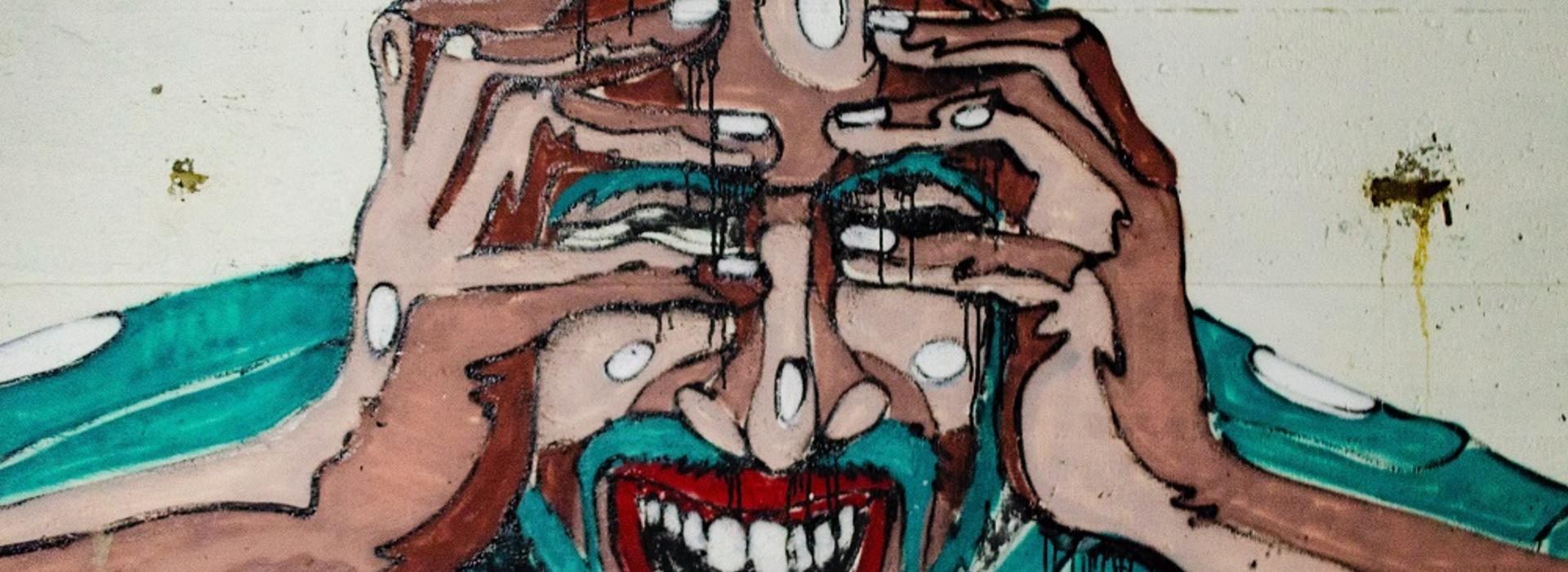

Understanding the complexities of PTSD

Assistant Professor Jacquetta Blacker (pictured below left), MD, MA, has been studying post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) for years. Her research and involvement in treating individuals with PTSD has taught her that it is a complex condition that plays out differently in each person it touches.

What is PTSD?

It is a condition in which a person struggles with the long-term after-effects of experiencing or witnessing a threatening event. It is a heterogeneous disorder, meaning different people experience different symptoms. The symptoms fall into certain categories. These include hyperarousal, such as being jumpy or easily startled, or finding that they lose their temper easily, re-experiencing in the form of flashbacks, bad dreams or intrusive thoughts, avoidance of things that remind them of the traumatic event. And finally, cognition and mood symptoms that might include memory and concentration difficulties, or feelings of depression and guilt.

What makes it so complex?

Most people who are exposed to a traumatic event do not develop PTSD, and for years, researchers have tried to work out why that is. We know there are risk factors that increase the likelihood of a person developing PTSD. Some of these include adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). ACEs include all sorts of things, from poverty, direct or indirect exposure to violence, neglect, child abuse, even having a family member in prison, and all of these things seem to prime a child’s brain so that they are more likely to develop PTSD as an adult if something bad happens to them. The more ACEs an adult has in their childhood, the higher their risk of getting PTSD after a trauma.

Why is it challenging to treat?

Because it is a heterogeneous disorder, two patients with the same diagnosis can have quite different symptoms. That makes it sometimes tricky for them to get the right diagnosis. Furthermore, a lot of people don’t seek help because they don’t necessarily see the symptoms as problematic straight away. They may assume it is normal not to sleep or to constantly get angry after something really bad has happened to them. That’s why it is so helpful to have an awareness in the community and among primary care providers, so they can help people spot what might be causing impairment. Some of the other difficulties include lack of access to resources. Right now, treatment of PTSD typically includes therapy with or without medications. But a lot of people struggle to even see a health provider who can make the diagnosis. Then they might face wait lists or a lack of therapists in their region.

What does your research tell you about the future of PTSD treatment?

We have already made some progress in prevention and treatment. There has been widespread adoption of Psychological First Aid* as a common sense and compassionate disaster response, although some limitations remain in the evidence for its effectiveness in preventing PTSD. Multiple therapies have been developed for treating people who are struggling with PTSD symptoms and these have generally been found to be effective, especially in cases of PTSD caused by a single traumatic event. They have also been medications, such as antidepressants, found to be helpful. Meanwhile, lots of research is being done into genetics, epigenetics (the study of the switches that turn genes on and off), and the inherited and environmental risk factors for PTSD. Lots of work still needs to be done, including about how PTSD differs between children and adults, how to prevent PTSD from occurring, and how to treat it — especially in complex cases in which someone has been exposed to multiple traumatic events.

Who is most likely to suffer from PTSD?

The ACEs that we talked about above are hugely significant. Importantly, in the current climate of examining racial disparities, urban versus rural socioeconomic differences, and intercommunity wealth and healthcare access inequities, you can easily see how some communities struggle with higher numbers of ACEs than others, putting both children and adults at higher risk of developing PTSD in response to a traumatic event. Additionally, some individuals and communities struggle with higher rates of complex PTSD, where a person might be struggling with multiple awful things happening to them (think trafficking victims, refugees, war zone survivors). And a lot of individuals struggle with multiple mental health issues, such as eating disorders, addictions, and depression, in addition to PTSD. All of these need to be addressed to help them reduce their symptoms.

How does racism affect the incidence of PTSD?

Research has shown that minority communities frequently struggle with higher rates of stress and higher rates of PTSD. The Civil Rights movement provided legal protections for individuals but could not impact social structures as effectively. Looking at the impact of racism from a PTSD perspective, it is very much about the individual’s context within the community. The effects of living in a marginalized community can be compounded by poverty or neglect, but can also be alleviated by supportive family and social networks, and access to resources.

How might the COVID pandemic play out in terms of PTSD? Especially among healthcare providers?

We are already seeing early accounts of higher rates of stress, anxiety, depression, and burnout in front-line healthcare providers. This includes everyone from the first responders who are attending multiple calls a day, to the emergency room and medical personnel who are dealing with higher numbers of patients who are much sicker than usual. The medical focus has appropriately been on managing the acute needs of the community during a pandemic, but I hope as a profession we can direct a compassionate focus to the psychological and emotional needs of healthcare workers, especially if the pandemic has a drawn-out course. I also think it is important to remember that patients globally have been struggling due to lockdown requirements. They are going through surgeries, childbirth, and medical hospitalizations without the companionship and comfort of their families and friends. And families, in turn, are suffering because they cannot be there for their loved ones. I think this has been especially hard when a loved one has died in hospital. I suspect we will see a lot of grief and trauma in our communities emerging into clearer awareness in the very near future. I don’t know whether this will translate ultimately into higher rates of PTSD, but I am confident that those of us in the medical and therapeutic professions are alert to this possibility, and we’re ready and willing to help.

* Psychological First Aid (PFA) is an evidence-informed modular approach to help children, adolescents, adults, and families in the immediate aftermath of disaster and terrorism. It was developed by the National Child Traumatic Stress Network and the National Center for PTSD, with contributions from individuals involved in disaster research and response. More information.