Cancer Treatment Research Breakthroughs at Medical School

Cancer research and treatments are constantly evolving. Prior to the last few years, “a cure for cancer” was a phrase rarely uttered by researchers and clinicians. At the University of Minnesota Medical School, leading-edge studies have uncovered new methods and combinations of cancer treatments that have the potential to forever change how doctors treat cancer.

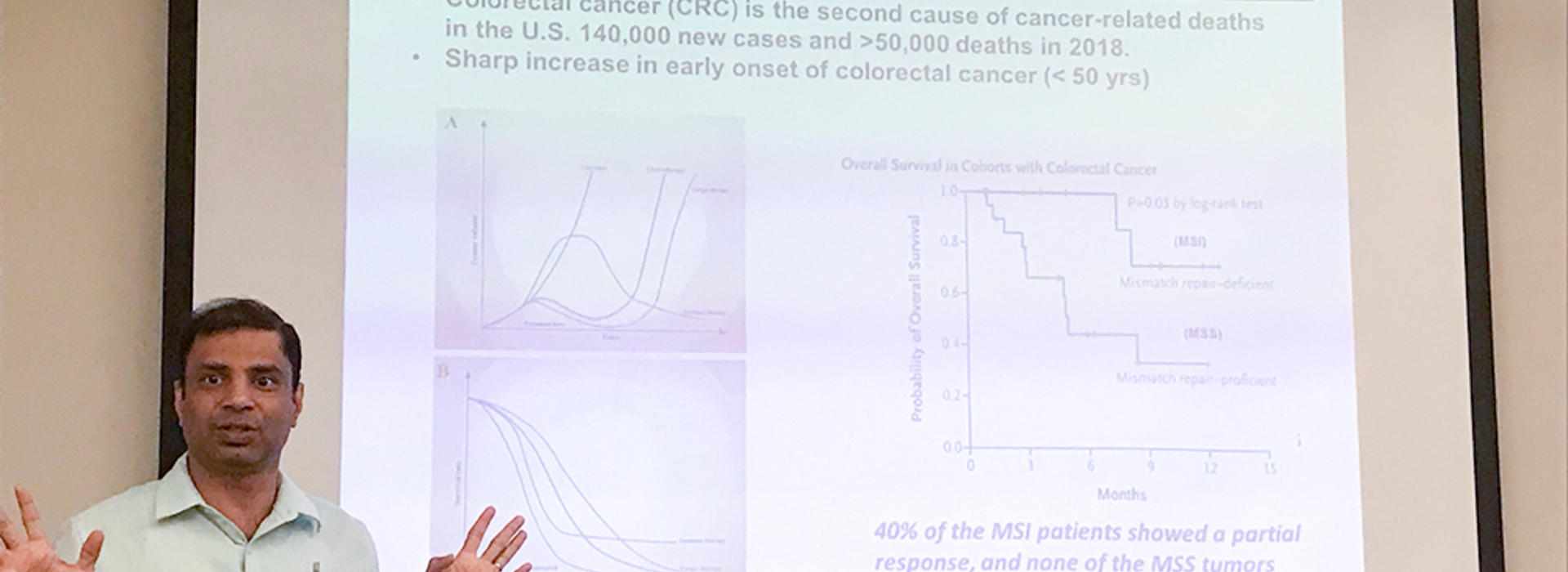

An associate professor in the Department of Surgery, Subbaya (Subree) Subramanian, MS, PhD, leads basic and translational research in his lab. When Dr. Subramanian first expressed to his fellow oncology and surgery colleagues his interest in modeling traditional cancer treatments (chemotherapy and surgery) in relation to immunotherapy (drug) response, they were excited and eager to learn the study results.

“This is one of the fundamental questions in cancer therapy,” Dr. Subramanian said. “We must learn how to best support the immune system for patients while using the tools we have, including invasive surgery, chemotherapy and immunotherapy treatments.”

Part One Study - Lymph Node Removal in Early vs. Late Stages of Cancer

The first part of Dr. Subramanian’s study was designed to examine the removal of lymph nodes near cancerous tumors. When cancer presents, tumors often affect the lymph nodes nearby—these nodes are response centers for our body’s immune system. Lymph node removal is often necessary because they are at risk for cancer metastasis due to their close proximity to the tumor.

The team studied the effects of surgically removing the lymph nodes beside tumors, known as tumor-draining lymph nodes (TdLNs), in early- and late-stages of cancer.

“As our models for these experiments, we studied tumors in mice,” Dr. Subramanian said. “In order to better understand how to treat cancer in humans, we need to model our experiments to examine the biological responses to our interventions.”

The cancerous cells in the tumor can drain and reach the TdLN, which makes the TdLN at risk for infection. However, while it is at risk, the TdLN can also be very useful as a frontline defense for the body’s natural immune response. This presents a difficult choice for surgeons and oncologists who must make decisions for cancer patients about if or when the TdLN should be removed.

Researchers in Dr. Subramanian’s lab compared the survival rate of mice after TdLN removal in early versus late stages of cancer. In the early stages of cancer, they found that intact TdLNs are essential for promoting anti-tumor immune activation and immunotherapy response. In late stages of cancer, the team found that TdLNs become unresponsive and are not necessary for immunotherapy response.

Dr. Subramanian’s conclusion in part one of his research is that immunotherapies are more effective in the early stages of cancer when the TdLN is intact.

Part Two Study - Sequential vs. Simultaneous Chemotherapy & Immunotherapy Treatments

Along with surgery, cancer patients often receive a combination of chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Immunotherapies are treatments designed to boost the body’s own immune response—a game changer in cancer treatment for oncologists—while chemotherapy still plays an effective role in killing cancer cells.

The question Dr. Subramanian and researchers sought to answer in this part of their study was how these therapies interact with each other and how to best leverage their benefits together to fight cancer.

“The second part of our study is very important,” Dr. Subramanian said. “We administered chemotherapy and immunotherapies in our mouse models both sequentially and concurrently. Our goal was to learn how these therapies behave in the body together to determine if there is an optimal combination and cadence of these therapies.”

In early stages of cancer, the team observed accelerated tumor growth after having removed the TdLNs in mice, despite the administration of immunotherapies. Additionally, the researchers observed that sequential chemotherapy followed by immunotherapy produced a significantly higher degree of anti-tumor response compared to a simultaneous, combined therapy approach.

“Timing of treatment is important for patient outcomes,” Dr. Subramanian said. “Specifically, we found that the most effective trial we observed was to administer chemotherapy followed by immunotherapy after nine days. This provides a clear synergy between the interventions.”

Dr. Subramanian’s manuscript of this study has been accepted as a research article in iScience.