Adding ‘Family’ Back into Medicine

Adding ‘Family’ Back into Medicine

U of M Medical School Leaders Discuss the Need to Recruit, Retain and Graduate More Family Medicine Physicians

Read time: 5.5 minutes

New data continues to unravel what is infamously known as the “Dean’s Lie” — between 2003 and 2014, nearly half of all MD graduates who matched into primary care residencies did not, upon completion of their residency, join a primary care practice.

This study, led in part by two University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth Campus faculty, illustrates the magnitude by which medical education institutions overestimate the number of graduating physicians who go on to practice in primary care. Of the 17,000 graduates from 10 institutions, only 22% practice in primary care settings today compared to the predicted (and publicly touted) 41%.

Knowing the actual numbers plays a key role in meeting a daunting workforce demand. Today, the federal Health Resources and Services Administration estimates the U.S. is short roughly 15,000 primary care physicians, particularly in rural and underserved communities. By 2033, the American Medical Association predicts that number will increase to 21,000.

Yet, a special type of intentionality may provide the cure.

“Intentionality with your missions is not a compromise of standards,” says Peter Nalin, MD, MBA, FAAFP, associate dean for rural medicine and head of the Department of Family Medicine and Biobehavioral Health at the U of M Medical School, Duluth Campus.

Dr. Nalin is one of several U of M Medical School leaders — on both the Twin Cities and Duluth campuses — focused on recruiting, retaining and graduating more primary care physicians, particularly into family medicine. Over the last several decades, this group of leaders has implemented various principles, programs and curriculum to create a pipeline to the practice — early exposure to clinical activity, longitudinal clerkships in rural and underserved communities, a seamless pathway to residency and a special, mission-driven campus.

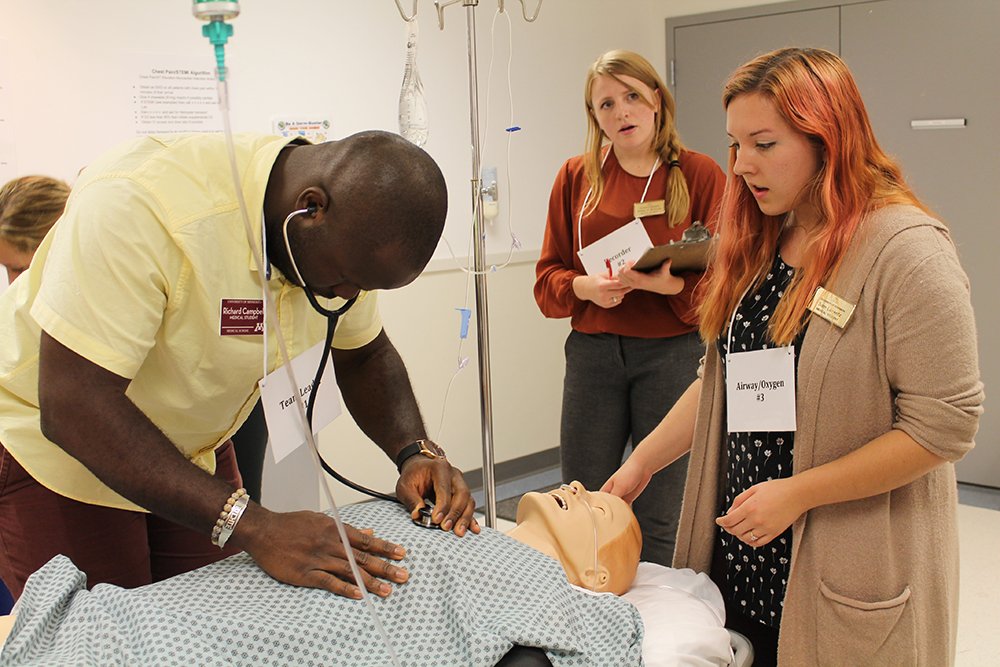

Early Exposure to Clinical Activity

“There is a traditional, ‘hidden curriculum’ in academic medicine that biases students away from primary care careers,” says James Pacala, MD, MS, head of the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health at the U of M Medical School, Twin Cities Campus.

The U of M Medical School combats that issue by ensuring student exposure to family medicine principles and experiences in several areas of its curriculum and programs.

“On the Duluth campus, our curriculum has emphasized early integration of clinical activity with the necessary foundational sciences,” Dr. Nalin says. “Medical students have a chance to achieve clinical competence sooner and use those skills longitudinally from an earlier point than traditional medical education.”

This includes what is known as the Rural Medical Scholars Program for first- and second-year medical students at the Duluth campus. This longitudinal curriculum, over the period of a few weeks, transplants medical students into the offices, hospitals — and sometimes, homes — of practicing rural physicians to gain early experiences with hands-on patient care.

“An important part of the course experience is either living in the vicinity of the doctor or literally living in their homes. Our medical students experience the office life and the home life of their host physicians,” Dr. Nalin says. Similar offerings at the Twin Cities campus are the Family Medicine Clerkship and the Urban Community Ambulatory Medicine (UCAM), with UCAM focusing more on underserved communities.

Longitudinal Clerkships in Rural and Underserved Communities

On the Twin Cities campus, third-year medical students can further their family medicine interests and expertise by applying for either the Metropolitan Physician Associate Program or the Rural Physician Associate Program (RPAP). These nine-month clerkships place medical students in underserved communities in either urban or rural settings to learn more about the communities and the day-to-day lives of their family medicine physicians.

This year, RPAP is celebrating its 50th class of medical students, and it boasts a proven rate of success. According to Dr. Pacala, more than 60% of RPAP students choose family medicine for a career.

Dr. Nalin says, “The continuity of the education really helps students demonstrate their enthusiasm and capability for learning, offering them more and more responsibility, as future family medicine physicians, throughout the experience of how rural patients get their care.”

A Seamless Pathway to Residency

Come time for medical students to express their interest and apply for residencies, as a U of M Medical School graduate, it is possible to continue their family medicine interests right where they started.

“Our department is somewhat unique in that virtually all of its clinics are also training programs. Many other family medicine departments will operate several clinics, while only one or two of them are residency sites,” Dr. Pacala says. “With eight residency programs — four core and four affiliated with the department — the atmosphere of family medicine training permeates the culture of our medical school.”

According to Dr. Pacala, the department has graduated more family medicine physicians than any other program in the last 50 years. It’s benefited the state of Minnesota in particular — more than 70% of Minnesota’s family medicine physicians graduated from U of M Medical School.

A Special, Mission-Driven Campus

“There are headwinds in recruiting students into family medicine,” Dr. Pacala said. “There is a myth that family physicians primarily take care of colds and other minor conditions. This is false — we see very complex cases. In our clinical practices, over half of the patients we see have three or more conditions that need to be managed. Family medicine is complex and challenging, yet fulfilling.”

Combine that with a higher likelihood of physician burnout, lower salaries than other medical specialities and the economics of medicine favoring procedural care and volume, and it becomes apparent how medicine overall devalues family medicine and other primary care physicians.

How, then, can medical students be recruited into the speciality of family medicine? At the U of M Medical School, leaders and visionaries have dedicated an entire campus to the mission.

“Without question, the Duluth campus mission has been a key factor in exposing students to family medicine,” Dr. Pacala says. “The campus has built rural family medicine into its mission statement and admissions criteria, and their medical students are steeped in family medicine from day one. This, in part, has led to our percentage of medical school graduates choosing family medicine being the highest among allopathic medical schools.”

Medical students accepted to the Duluth campus must demonstrate a motivation and passion for a career in medicine serving people in rural or Native American communities. Although medical students can choose to opt-in to a two-year elective to learn about Native American health, all medical students complete a required curriculum that introduces both rural medicine and Native American health as one comprehensive course.

“One of our courses is ‘Intro to Rural Family Medicine and Native American Health,’ so it’s not two separate introductory courses. It’s one collaborative course experience,” Dr. Nalin says. “The combination reflects the fact that both mission areas are supported here and interrelated to each other.”

The future doctors study for two years at the Duluth campus before finishing their final two years at the Twin Cities campus.

“Medical education at Duluth is part of the pathway that delivers our outcomes. We make a point to find and encourage medical students who want to practice family medicine,” Dr. Nalin says.

Honing in on the Success

By integrating clinical activity early in the first and second years of medical school, embedding medical students into the communities and homes of practicing physicians, offering seamless pathways to residency, as well as having a mission-driven focus — like serving rural and Native American communities — more and more medical students at the U of M Medical School elect to pursue a career in family medicine.

Despite this success, both Dr. Pacala and Dr. Nalin agreed that more work needs to be done at the U of M Medical School and across the U.S. for medical education institutions to grow the workforce that’s needed now and in the future.

“We must continue our steadfast commitment to training family physicians, deliver even more on our academic work — both in research and teaching — and better advocate for value-based care, health equity and the value of generalism in medical care,” Dr. Pacala says. “All of these are bedrock principles that are served well by family medicine.”

#3 in Blue Ridge Institute NIH Rankings

The NIH is the largest federal provider of basic research money to universities. Each year, the Blue Ridge Institute evaluates NIH data tables and ranks universities based on their annual NIH grant support. For 2019, the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health ranked at #3.

Native Americans Into Medicine

This 47-year-old academic enrichment program is offered through the U of M Medical School's Center for American Indian and Minority Health. The program takes place each summer, building interest among Native American college sophomores and juniors about careers in medicine. The U of M Medical School, Duluth Campus is #2 in the nation for graduating American Indian physicians.

Family Medicine Interest Group

On both the Twin Cities and Duluth campuses, the Family Medicine Interest Group (FMIG) is an extracurricular organization for students interested in family medicine. On the Duluth campus, it is one of the largest, most active student groups made up of class-elect first and second-year students. For the last three years, the Duluth campus’ FMIG has received national recognition from the American Academy of Family Physicians.