Battling Cervical Cancer with Social Media

Her career in medicine started with music. Deanna Teoh, MD, MS, who is an assistant professor in the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Women's Health at the University of Minnesota Medical School, embarked on her undergraduate studies as a dual major in music and women’s studies. During her deep-dive into deciding her future, she noticed a common thread in her women’s studies coursework.

“I realized that anytime I got a choice to write a paper, it was tied to women’s health care. I started realizing that’s what I was really interested in,” she said.

And so, her passion for medicine began. Dr. Teoh stepped into medical school with the intention of pursuing women’s health to, hopefully, help deliver babies one day. After doing a rotation in gynecologic oncology, her calling found new inspiration once again.

“Cancer as a topic is just fascinating if you take the person out of it,” she said. “The relationships you form with your patients, in a very tough time in their lives, is amazing. You see some of the greatest strengths in humanity when you work with really sick patients, and you form these unique relationships that I absolutely love.”

An expert in preventing and treating cervical cancer

Today—a leader in academic medicine—Dr. Teoh focuses on both the research, prevention and treatment of cervical cancer. Very soon, her team will open a clinical trial for cervical cancer treatment focused on patients who receive chemotherapy and radiation. The trial will analyze if the incorporation of an additional drug into their treatment plan can improve the patients' outcomes.

Another clinical trial she hopes to launch will focus on treatment of HPV infection, the human papillomavirus—a sexually-transmitted disease and leading cause in cervical cancer and other conditions and diseases.

“Right now, there is an HPV vaccine to prevent HPV infection and prevent precancerous changes in the cervix,” Dr. Teoh said. “But, for people who are already infected with HPV, we don’t have any treatments specifically to eradicate the virus.”

More than 79 million Americans, most in their early teens and 20s, are currently infected with HPV. Dr. Teoh says that number also includes women in their 40s and 50s who, before 2006, did not have the option to get the vaccine.

“We do screenings for cervical cancer, and if we find precancerous cells, we can treat those and prevent people from getting cancer. It’s an effective strategy but not without some risk,” Dr. Teoh said. “We actually can’t treat the virus; we just treat those changes in the cervix. For these people who are infected with HPV, is there a way we can actually treat the virus?”

The idea for this proposed clinical trial involves studying patients who have the two most common HPV strains linked to cervical cancer—HPV 16 and 18. Dr. Teoh says if she is able to open the trial, the University of Minnesota will be one of only a few sites testing a vaccine to eliminate HPV in someone already infected with the virus.

“Can we give them a vaccine that gets rid of the virus, and then after clearing the virus, remove their subsequent risk of precancerous changes?” she explained.

Battling social misconceptions

Her toughest battle in ensuring that patients avoid cervical cancer is overcoming public misconceptions about HPV and its preventative vaccine. The availability of the vaccine in 2006 coincided with an emergent, general distrust in vaccinations as a whole. Many also question why the vaccine is needed if doctors have successfully decreased incidences of cervical cancer over time.

“If you look from the 1950s to now, even before the HPV vaccine was invented, we actually decreased cervical cancer,” Dr. Teoh said. “What a lot of people don’t realize is that there’s no screening test that is 100% effective. I have patients who have had screening tests, per the guidelines or even in excess of the guidelines, who still end up with cancer.”

She continued, “People always think of HPV and cervical cancer, but what people miss is that there’s a lot of other HPV-related cancers. Actually, the most prevalent one right now is head and neck cancer. But it’s anticipated that if you get the HPV vaccine, you will significantly decrease your risk of getting all cancers related to HPV.”

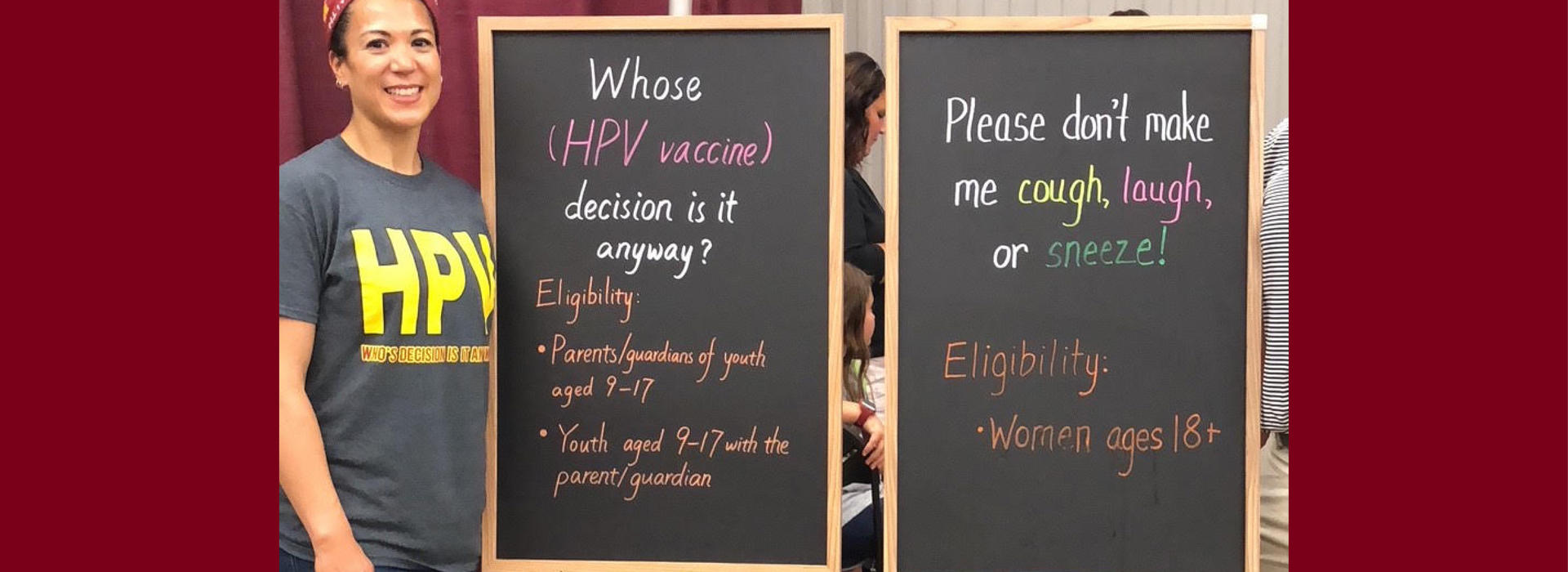

Dr. Teoh believes one of her best tools in preventing cervical cancer doesn’t come from a lab. It’s social media. During the month of January, which is Cervical Cancer Awareness Month, she has seen several misinformed posts about cervical cancer, HPV and the vaccine. Her work on a roundtable, appointed by the American Cancer Society, plans to form new strategies to battle negative or inaccurate sentiment on the topic.

“A lot of my work looks at the best ways to target young adults on social media because we know that young adults tend to not go to the doctor for routine health care,” Dr. Teoh said. “You see these horrible reported events following vaccination, whether they are true or not, and unfortunately, that gets to people who are on the fence, more so than our facts and figures. I’m a physician. I’m a researcher. So, I like facts and statistics, but I can get how somebody would see a horrendous picture, and then that stays with them more than the Center for Disease Control’s bar graph.”

Dr. Teoh recently spoke at the American Society of Clinical Oncology Conference and the NRG Oncology Conference, offering physicians tips and tricks on using social media to spread general health awareness.