Cleft, Craniofacial Surgeons Enlist Students, Trainees for Surgical Outcomes Research

Being the best at what you do is critically important in the world of healthcare. Unlike sports, where “the best” is about gold medals or championships, faculty physicians at the University of Minnesota Medical School strive to be the best for their patients' well-being and—as leaders in academic medicine—for their fellow physicians around the world.

Many consider Brianne Roby, MD, and Robert Tibesar, MD, both assistant professors in the Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, as some of the best in pediatric cleft palate and craniofacial surgery. Not only do they practice at Children’s Minnesota, they also care for patients at M Health Fairview University of Minnesota Masonic Children’s Hospital—all while training Medical School students and trainees and conducting academic research that evaluates their own surgical outcomes.

“For us, as surgeons, our research is two-fold,” Dr. Tibesar said. “It disciplines us as surgeons to work harder, be better and critically evaluate what we have done so far. And then, we share those conclusions with our colleagues across the country.”

“And, when we’re looking at patients who will need multiple surgeries over their lifetime,” Dr. Roby added, “it behooves us to minimize extra surgeries related to complications and to make sure that they have the best outcomes, so that they have good social interactions with their peers and colleagues going forward.”

In the past 10 years, the duo has led several research studies focused on cleft and craniofacial surgical outcomes—from airway issues in children with Pierre Robin syndrome to rhinoplasty surgical repair in young adults with cleft lips. Some of these studies have enlisted the support of Medical School students and trainees, including one using eye-tracking technology.

“We were the first team to have kids use eye-tracking technology on other kids, which was published a few months ago,” Dr. Roby said. “A medical student took the lead on this project that looked at how kids view other kids with cleft lip scars, which would help us see what we can do to make things better for our patients’ interactions with their peers.”

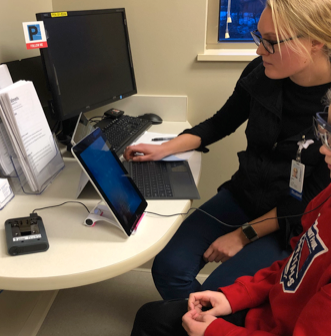

This medical student, now an MD—Emily Karp—took a year off in between her third and fourth year at the Medical School to work with Dr. Roby. Dr. Karp first developed the protocol, and then spent six months in local clinics and emergency departments to collect data from a couple hundred children. After an analysis, Dr. Karp presented their team’s findings at a national meeting in San Diego.

“That project would not have been possible without her,” Dr. Roby said. “I did not have time to go spend four hours in an emergency department or in a primary care clinic trying to get a five-year-old to put eye tracking glasses on. And, after it was published, we got a grant to explore this idea further for a much larger study.”

Drs. Roby and Tibesar shared additional examples of when the department’s particular culture of involving students and trainees in research gave their learners rare, national recognition early in their careers. But beyond resume-building, they both believe they’re instilling a “drive to discover” in every person they mentor.

“If we can send lots of people out into the world after their training to continue similar goals and dreams of making things better for this population, I think that’s one of the biggest successes we could have,” Dr. Roby said. “Because we’re not only helping our patients, but we’re helping all of their future patients as well by getting that interest in researching outcomes instilled in another generation of people.”