Dr. Harry T. Orr awarded Kavli Prize in Neuroscience

For patients diagnosed with the rare neurological disorder spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA 1), life is challenging. The disorder is progressive and incurable, meaning that when a patient is diagnosed, typically between the ages of 30 and 40, they must grapple with the devastating reality that their life will never be the same. Symptoms of SCA 1 include loss of coordination, slurred speech and slowed eye movements. Patients are often perceived as intoxicated and face social discrimination as people tend to assume they are simply drunk in public. Despite these challenges, families affected by the hereditary disorder can place hope in the work of Dr. Harry T. Orr, PhD, Director of the Institute of Translational Science at the University of Minnesota Medical School, whose decades-long research of SCA 1 is nearing the development of an effective treatment.

The totality of Dr. Orr's research, spanning from identifying the underlying gene causing SCA 1 to working with companies to create a treatment, earned him the prestigious Kavli Prize in neuroscience this year. Established in 2005 by the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, the Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research, and the Kavli Foundation, the objective of the Kavli Prize is to honor scientists transforming our understanding of "the big, the small, and the complex'' - astrophysics, nanoscience and neuroscience. Since the first Kavli Prize laureates were named in 2008, ten have gone on to win Nobel Prizes.

Alongside longtime friend and research partner Dr. Huda Zoghbi and two other leading neuroscience researchers, Dr. Orr received his award from the King of Norway in Oslo on Sept. 6. Dr. Orr described learning he was a Kavli Prize laureate as "the most exciting news I've ever gotten about my career." The moment was the culmination of a decades-long love of science that took off during an undergraduate biology class.

"As part of my TA responsibilities for a biology class at Oakland University in Rochester, Michigan, we were exposing frog embryos to pesticides, and it was just very intriguing that it seemed to affect the neurological function of the animals,” Dr. Orr recalls.

A research advisor noted Dr. Orr's interests and recommended that he go to Washington University in Missouri to pursue a PhD in neuroscience.

"That was basically the start," he explains. "I wanted to learn the modern molecular biology methods, so I went and did a postdoc at Harvard working on immunology and specifically human leukocyte antigens (HLA)."

Dr. Orr was still studying HLA when he happened to sit next to a fellow researcher on a bus during a conference who encouraged him to apply for a job at the University of Minnesota. Shortly after he came to the Medical School in the early 1980s, neurologist Dr. Lawrence Schut knocked on Dr. Orr's office door and changed the course of his career forever.

"Dr. Schut had just found out that the gene causing SCA 1 in his family was located close to the HLA complex. It didn't take long before we dropped our HLA projects and shifted solely to neuroscience and SCA 1," recalls Dr. Orr.

Dr. Orr's motto is "keep your door open," and never did that mantra influence his life and research more positively than when it led him to Dr. Zoghbi, a then trainee at Baylor University studying ataxia genes. Dr. Zoghbi shared findings that helped Dr. Orr obtain data indicating the position of the ataxia gene. From there, the two decided to collaborate. In his Kavli Prize bio, Dr. Orr wrote that this was "the smartest decision I have ever made in my scientific career," and receiving the Kavli Prize alongside Dr. Zoghbi years later was a profound moment.

"To be honest with you, that is the most beneficial, most positive feeling," he says, "that they recognize the collaboration. Sometimes awards can be divisive to research, but in this case, I think a major aspect of us getting the award, in addition to the scientific advances of the two of us, is the fact that we collaborated for over 30 years."

Collaboration is central to Dr. Orr's work. He says collaborating with colleagues is his favorite aspect of research and credits much of his success to his collaborators, namely Dr. Zoghbi, lab manager Lisa Duvick, and countless colleagues and students throughout the years.

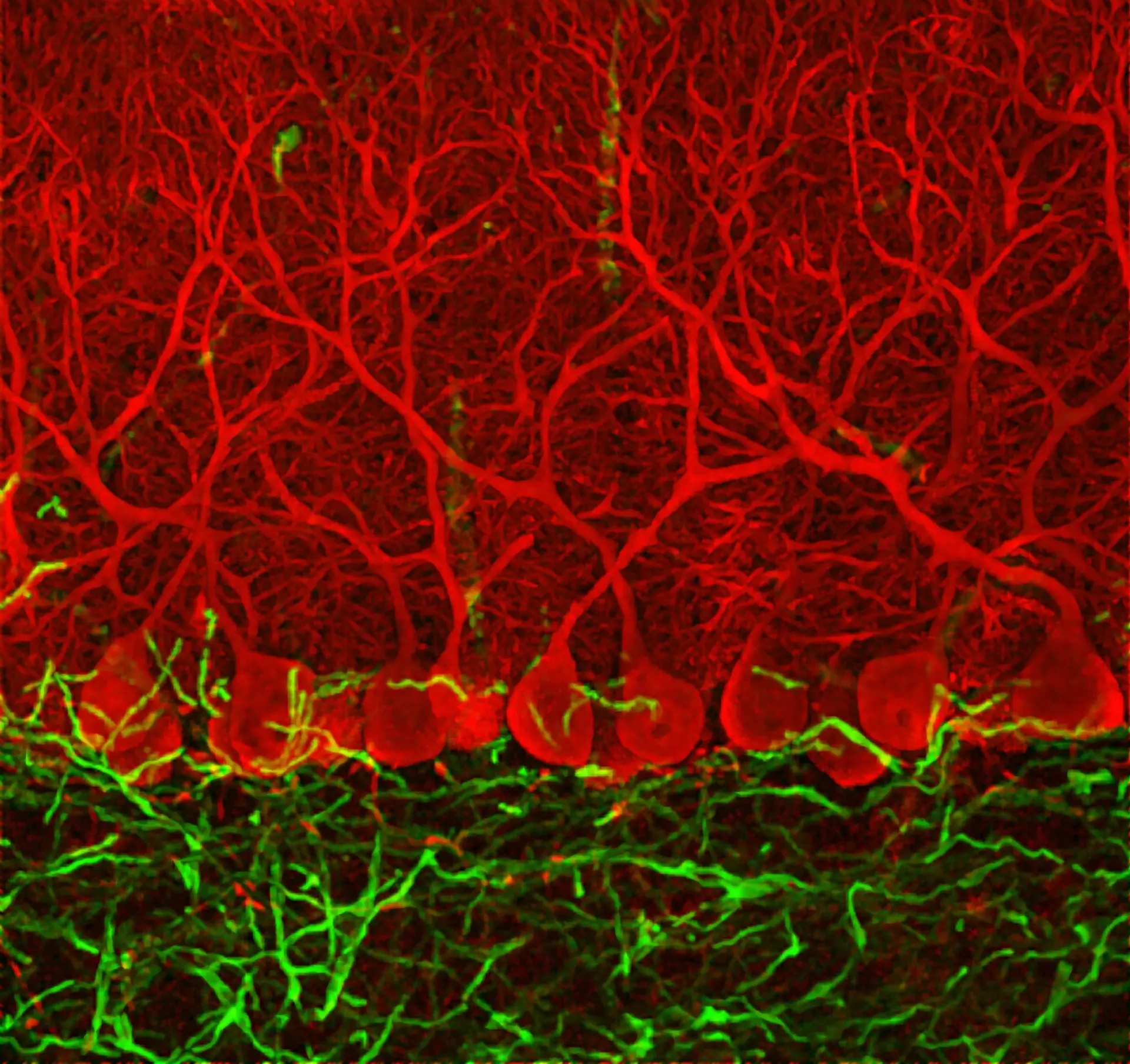

Roughly 30 years after the fateful day that Dr. Schut knocked on his door, Dr. Orr's lab has made outstanding advances, using mouse models to test how SCA 1 might develop, find underlying molecular mechanisms of the disease and discover which regions of the brain and peripheral tissue are affected. Although receiving the Kavli Prize has been exciting and gratifying, it is the science and the people that truly motivate Dr. Orr.

"What really drives me now is the families affected with this disease," he explains. "They've been so supportive of our work, and they're such terrific people. I really feel we owe them a lot and need to focus on giving them some positive benefits for all their efforts in supporting our research."