Health Disparities Study Tests Mobile App’s Effectiveness in Treating Alcohol Use Disorder

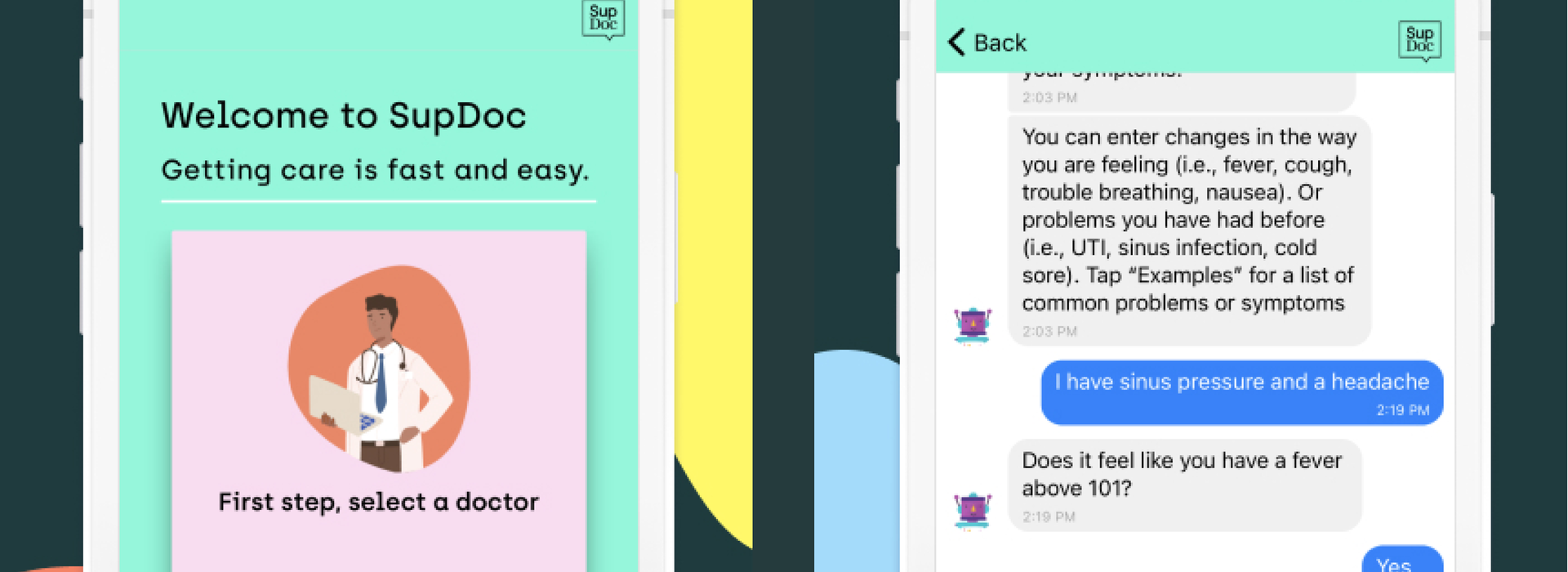

A cell phone app may soon become an effective way in treating alcohol use disorder (AUD) — and, possibly other chronic conditions — thanks to a pilot study underway at the University of Minnesota Medical School. Researchers teamed up with SupDoc, a virtual healthcare app, to answer a question.

“In areas where there is not a lot of access to either primary care and/or mental health services, can we leverage technology, such as SupDoc, to help reach out to people with AUD and keep connected to a larger number of them while using fewer resources?” asked Christopher Warlick, MD, PhD, associate professor and head of the Department of Urology at the Medical School, who leads the study.

Dr. Warlick and Collin Calvert, a fourth-year PhD student at the School of Public Health, will work with Michael Brombach, the CEO and founder of SupDoc, to develop a specific module within the app tailored to engage and treat a subset of patients with AUD. The study, funded by the Medical School’s Rapid Response Grants for Reducing Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare, addresses the fact that “despite consuming less alcohol than whites, people of color (POC) experience worse alcohol-related health consequences.”

“Alcohol consumption remains a major cause of public health problems, including suicide, cirrhosis, and several cancers … While AUD treatment is an effective way of curbing alcohol consumption, POC are also less likely to have access to these services due to systemic and structurally racist barriers, including lack of insurance, poverty and lack of transportation,” reads a statement on the grant’s website.

The pilot study will enroll a small number of Black men with AUD to determine if the mobile app is an effective way of engaging and intervening with them. Participants in the study will receive regular notifications from the app, asking them a set list of questions related to their AUD that evaluate mental health and risk for relapse.

“If somebody is dealing with a crisis or thinks they are at risk for alcohol use, then this app could be a quick way for them to get in contact with a healthcare provider to let them know that they are near a crisis, and then that healthcare provider can proactively intervene,” Calvert said.

Not only would the app benefit the patients but also their healthcare providers. The research team describes today’s busy clinics and hospitals as resource-constricted, treating hundreds of patients daily with only a set number of professionals to care for them. Sometimes, those patients require regular check-ins, usually by phone — a near impossible task, according to Dr. Warlick.

“If you have 100 patients who are potentially at risk of relapsing for alcohol use, it would be difficult for anybody to individually call 100 patients per day to follow-up and ask how they are doing,” Dr. Warlick said. “But, if we can proactively use technology to ping them, and then we get responses (in a perfect world) from all 100, where 90 of those patients indicate they are fine, while 10 say they are heading toward crisis, then we can use the limited resources we have to proactively intervene where they are needed the most.”

Over the next year, the research team will collect data through the app to determine, first, if patients even use the app by monitoring their retention and response rates. If the study shows high engagement rates, then they plan to use the results to develop a larger study with more patients to garner stronger indicators on whether or not the app is truly effective in treating AUD.

“We’re building out a better way to care for patients who are disenfranchised, can’t get easy access to healthcare or have more complex health issues. You can’t always bring these patients into a doctor’s office or deliver care the way you always have. We’re providing a way for these patients to get quick care wherever they are, whenever they need it,” Brombach said. “I can see this platform really having an impact with all chronic diseases.”

Dr. Warlick added, “While we are targeting this intervention as a way to address health disparities, the reality is that if this sort of technology works, there’s no reason to think that it couldn’t work broadly across all populations. Often, as it turns out, if you’re ensuring that you are providing care for the most marginalized populations, typically the care for all populations rises.”