Infant Saliva Samples May Bring New Data to Inform COVID-19 Transmission Theories

With the help of days-old infants, new life may bring new answers to the growing list of theories about COVID-19 transmission and its first infection in Minnesota.

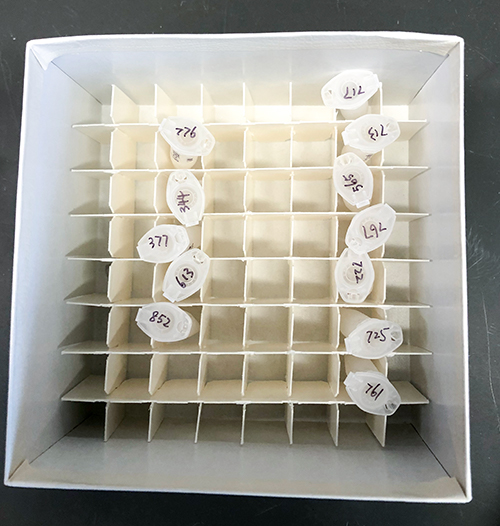

A University of Minnesota Medical School study supported by a CO:VID (Collaborative Outcomes: Visionary Innovation & Discovery) grant will tap into already existing research samples collected by Mark R. Schleiss, MD, American Legion and Auxiliary Research Foundation Chair and professor in the Department of Pediatrics. These samples—saliva swabs collected from infants within hours to a couple days after being born—are part of Dr. Schleiss’ decades-long research into CMV, or cytomegalovirus. Since 2017, he’s collected more than 20,000 samples.

“Most of my career has been devoted to an infection called CMV, which is actually the single-most common infectious disease in the United States that causes birth defects in newborns,” Dr. Schleiss said. “The collection of those samples was really for the study of CMV, but they’ve been in the freezer, and we thought, ‘Well, this could give information on two important questions related to COVID-19.’”

Question one—can pregnant mothers transmit COVID-19 to infants in the womb? If Dr. Schleiss finds the virus’ RNA in any of his samples, that information could lead to a new focus on COVID-19 patient care for pregnant mothers and their unborn infants.

“If we find this, it means that there’s transmission—at least the RNA—from mother to baby. What are the consequences of that? What do we need to understand about that?” Dr. Schleiss said. “That’s pretty interesting in its own right because, even after all these months of COVID-19 research all over the world, it’s still controversial on whether or not true infection is transmitted from a mother infected with COVID-19 to the newborn. This would add to that knowledge—we may not solve it, and if anything, it may muddy the water more.”

Question two—will these samples show that COVID-19 arrived in Minnesota earlier than March? Although Dr. Schleiss’ samples go back to 2017, he plans to analyze only the samples that date back to late fall of 2019.

“Presumably there’d be no chance that we’d find anything prior to December, but we wanted to go back a little bit further to make sure all of the samples that we thought really should be negative are, in fact, negative,” Dr. Schleiss said. “People still argue about where this virus started and how it got to America. It’s interesting to see if this information will help tell the story about the virus and how it evolved.”

By August, Dr. Schleiss plans to have tested all of his samples. He’s using a validated assay developed in his laboratory—a PCR process—that tests with the same primers developed by the Minnesota Department of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He hopes his findings, whether positive or negative, will coincide with a larger conversation around COVID-19 vaccines about who to give them to and when.

“Will a vaccine be something that’s earmarked just for people over the age of 65 who are at highest risk, or do we want to earmark vaccinating everybody with the idea of really controlling the disease at the population level? And, what about pregnant women?” Dr. Schleiss asked. “Pregnant women get the short end of the stick when it comes to research—therapies, vaccines and interventions are understudied in that population. If we understand issues related to COVID-19 transmission, then we might be able to make a convincing case for evaluating vaccines for those women.”