New Findings of Atherosclerosis Identified in U of M Medical School Study

A study led by researchers in the Center of Immunology at the University of Minnesota Medical School has formed new answers to one of the most common diseases in adults — atherosclerosis, or the build-up of fats, cholesterol and other substances in and on the artery walls. According to the research, which has been published in the journal, Nature Immunology, this build-up can reduce blood flow and cause instability and thrombosis, leading to cardiovascular disease, heart attack and stroke.

“Collectively, cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the U.S. and the world, yet mechanisms regulating the initiation of atherosclerosis remain unclear,” said Jesse Williams, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Integrative Biology and Physiology, a member of the U of M Center of Immunology and first author on the paper. “Understanding the cellular origin, diversity and dynamics that lead to atherosclerotic plaque formation and growth will allow for development of future therapeutics to better control disease progression.”

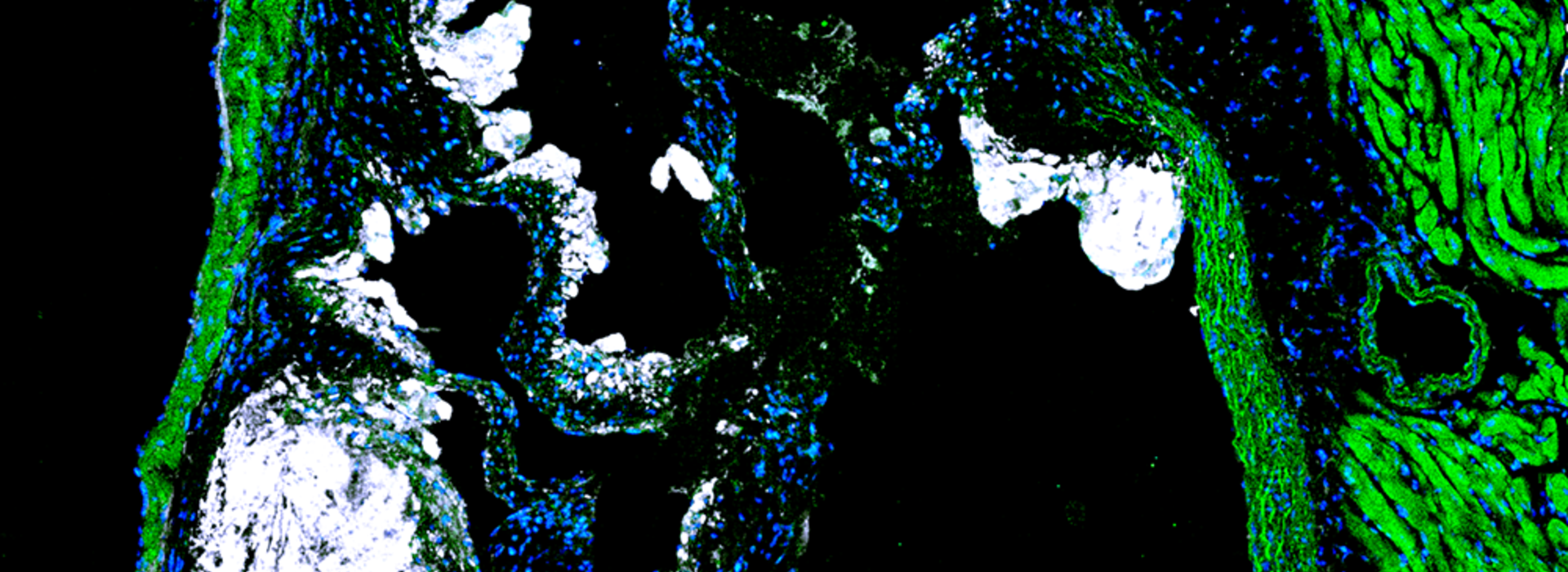

To gain this understanding, Dr. Williams led an international team, including researchers in St. Louis, Chicago, Canada, France, Russia and Korea, with funding through an R00 award from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. His lab utilized single-cell gene expression technology to identify immune cell diversity in the non-diseased mouse aorta and described a new Aorta Intima Resident Macrophage (MacAIR) population that resides in locations prone to developing atherosclerosis.

“We performed in-depth characterization of these macrophages, finding they were dependent upon a growth factor, known as Csf-1, for survival, and that in the non-diseased state, their local proliferation could sustain the population in the tissue,” Dr. Williams said. “During atherosclerosis progression, these macrophages were the first cells to take up cholesterol and were required for early atherosclerotic lesion development.”

Dr. Williams’ team performed fate-mapping studies to track these macrophages and found that their contribution to plaque development was short-lived. Instead, they noticed that the recruitment of circulating cells from the blood were required for plaque expansion and largely overtook the initial resident macrophage population.

Similarly to the non-diseased state, Dr. Williams’ team also performed single-cell gene expression sequencing of immune cells in the aorta from intermediate and late-stage disease samples, where they determined that the cells entering the atherosclerotic lesions aligned their gene expression profiles with the original resident macrophage population. This helped the team identify the genes associated with tissue residence in the artery wall, in the absence or presence of atherosclerotic disease.

“These data lay the foundation for future directed studies to determine the mechanisms that each of these newly identified genes play in atherosclerosis progression,” Dr. Williams said. “Our work defines the key cellular players in disease initiation as well as gene programs that are adopted by macrophages that take up residence within the aortic intima. However, the roles that these genes play at promoting cell survival, function and arterial remodeling have yet to be studied.”

Dr. Williams says his paper also discusses that the mechanisms previously proposed to maintain cholesterol-loaded macrophage populations in more established lesions, such as local proliferation, are unable to sustain macrophage populations within the initiation and expansion phase of atherosclerosis.

“My lab's current and future work will be to understand the principles driving these differences in macrophage function and maintenance in plaque, which we hope will lead to better therapeutic opportunities for intervention in early versus late-stage atherosclerosis patients,” Dr. Williams said.