A New Outlook on Eating Disorders Through Neurofeedback and Cognitive Research

Millions of people worldwide wrestle with mental health. Among mental health syndromes, eating disorders in particular are associated with an especially high risk of premature death. According to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders, approximately eight million people in the U.S. have anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and other eating disorders.

Associate Professor Carol Peterson, PhD, and Assistant Professor Ann Haynos, PhD—both in the University of Minnesota Medical School’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences—and their team members from the Minnesota Center for Eating Disorders Research are taking a fresh look at emotions and eating disorders. They hope to use their therapeutic research and mechanistic science to better understand the brain and develop life-changing therapeutic interventions for people with eating disorders.

Eating Disorders and Neurobiology

The role of emotion in eating disorders is an area of primary focus for Drs. Peterson and Haynos. They are working to identify the exact ways in which emotions are processed by people with eating disorders using the data they collect from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology.

In one of their mechanistic studies, Drs. Haynos, Peterson and their colleagues administer a chemical called oxytocin through a nasal spray to people with eating disorders and observe the impact it has on their brain using an MRI machine. This chemical, otherwise known as the “love hormone,” is produced in the brain and affects social bonding, emotion and eating habits. Some evidence suggests that people with eating disorders, such as anorexia nervosa, may produce lower levels of oxytocin.

“By understanding how our dose of oxytocin among individuals with anorexia nervosa affects the brain, eating behaviors and the experience of emotions, we can learn about the mechanisms of eating disorders as well as identify a potential intervention,” Dr. Peterson said.

To identify more ways the brain works, another portion of Dr. Haynos’ research focuses on showing people with eating disorders information about how their brains respond to stressful pictures in real-time while they are in an MRI machine.

“We use MRI machines to locate the activity in the feeling parts of the brain when a person is distressed. We then show participants how high the activity is in these parts of their brain and let them use this information to change their own brain patterns,” Dr. Haynos said.

Dr. Haynos notes that neurofeedback is not yet an approved therapy for eating disorders but may be a revolutionary way to teach people with eating disorders about how to change their emotions by changing their own brain signals.

Eating Disorders and Decision-Making

The way people make decisions about activities that make them feel good is central to mental health. Similar to people who suffer from addiction, those with eating disorders have strong thoughts about achieving rewards, inhibition and a sense of control.

According to Dr. Haynos, there are two areas of the brain that must communicate with each other to produce a healthy thought process: the side of the brain that processes wants and rewards and the side that drives inhibition and control. In the cases of patients with eating disorders and addiction, these two sides of the brain do not adequately correspond with each other. Researchers have found that for patients with bulimia nervosa, the planning stages of a binge have powerful effects on the reward center of the brain.

“What we understand with binge eating behaviors is that, over time, their dietary rules are so strict that it comes to a point that they simply cannot follow them anymore. This often results in over-consumption or a binge,” Dr. Peterson said.

The distinction between effort-full and effort-less self-control in eating disorders is another facet of Dr. Haynos’ studies. According to her research, bulimia nervosa may involve a form of effort-full self-control, whereas anorexia nervosa may involve effort-less self-control because patients with this disorder rely on their rules to automatically make decisions for them very quickly. In both cases, the way decisions are made becomes imbalanced.

“Too much self-control can be as harmful as too little self-control when it comes to mental health,” Dr. Haynos said.

Eating Disorder Treatment

Eating disorders can have serious medical and psychological risks, but they are also treatable conditions. Drs. Peterson and Haynos, along with their collaborators, have developed several psychological treatments to target both emotions and behaviors.

Dr. Peterson is one of the main developers of Integrative Cognitive-Affective Therapy, which has been found to be helpful for the treatment of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. This treatment evolved from their lab’s mechanistic research and highlights the important effects that “momentary” negative emotions, such as sadness, guilt and anxiety, have on eating disorder behaviors.

“Focusing on emotion regulation skills to target those painful emotions, rather than avoiding them, can help individuals with eating disorders change their behavior patterns,” Dr. Peterson said.

More recently, the researchers have adapted a treatment for anorexia nervosa that was developed for depression and anxiety, called Positive Affect Treatment. Dr. Haynos explains that this treatment focuses on building positive emotions and life purpose.

“It is not enough for us to help people to stop having an eating disorder. We also have to help them build a full and meaningful life,” Dr. Haynos said.

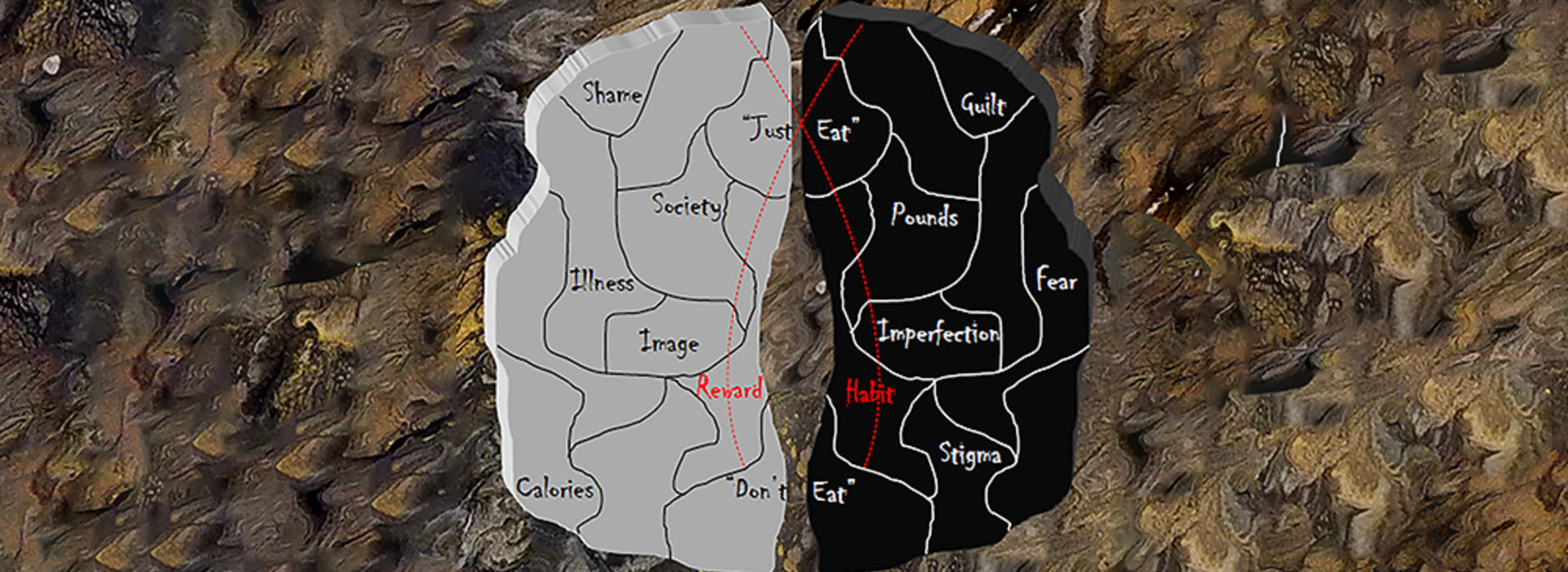

Photo: "Dichotomous Mind" by Nitya Chandiramani (Visual Artist) and Rebecca Houston (Visual Artist/Writer) was developed through in-depth conversation with Kathryn Cullen (Child Psychiatrist) and Ann Haynos (Clinical Psychologist), and in consultation with Yuko Taniguchi (Poet), to capture the mechanisms of the human brain impacted by anorexia nervosa and how this disease is experienced in the human mind and body. This project challenged scientists and artists to create a piece that is scientifically informative while retaining artistic authenticity and accurately depicting mental health challenges without reinforcing or promoting stereotypes.