Talking healthy vision with U of M

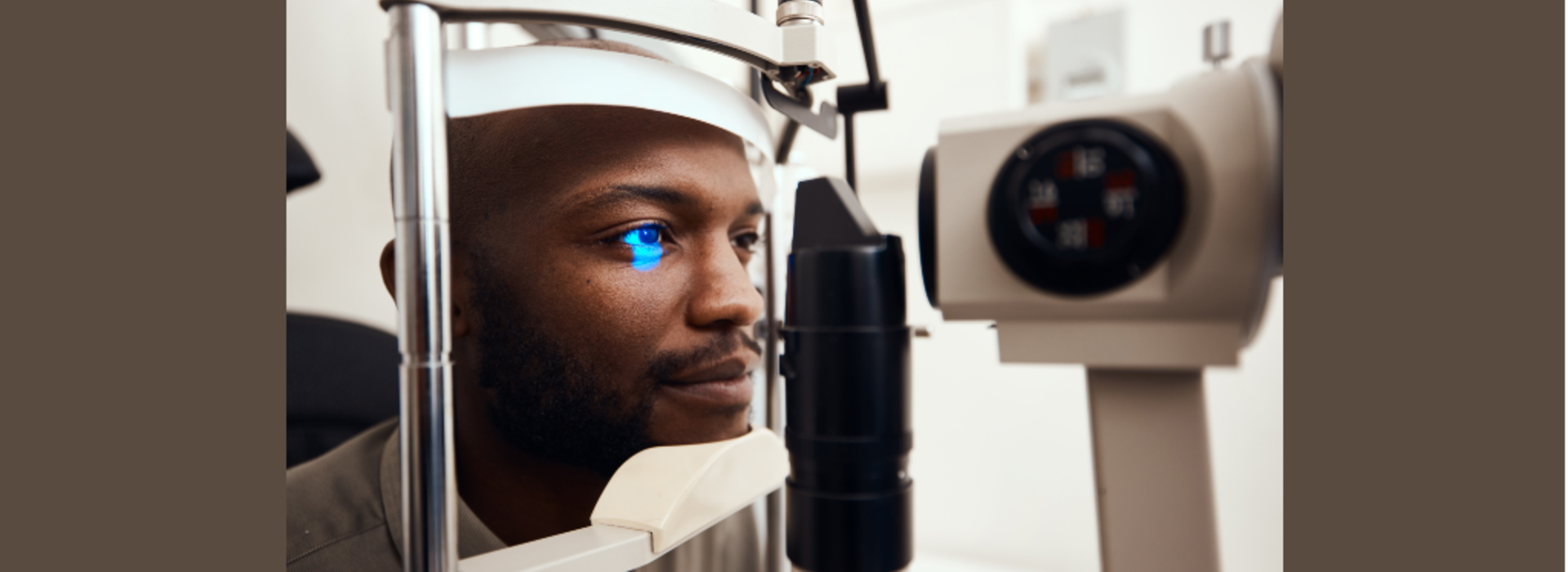

MINNEAPOLIS/ST. PAUL (05/15/2023) — May is Healthy Vision Month—a time to raise awareness about eye health and the importance of maintaining healthy vision.

Dara Koozekanani, MD, PhD, with the University of Minnesota Medical School and M Health Fairview, talks about the steps anyone can take to protect their vision, the impact of screens on eye health and his work at the U of M.

Q: What are some proactive steps people can take to protect their vision?

Dr. Koozekanani: It’s important to get regular eye exams that include dilating the eyes. This is important to ensure the entire eye is healthy and that there are not any undiagnosed, asymptomatic problems. Many diseases may not cause symptoms in the early stages when they are much easier to treat. The recommended frequency of dilated eye exams varies with age. The American Academy of Ophthalmology advises a dilated eye exam once in your 20s, twice in your 30s and at age 40. After that, the frequency would depend on what if any problems are found. After age 65, a dilated eye exam is advised every 1 to 2 years.

It’s also crucial to protect your eyes from injury. Wear appropriate protective eyewear at work or home when using power tools or performing other activities with the potential for flying debris. Any task hitting metal or stone objects together, such as hitting a chisel with a hammer, can launch fragments into the air. High velocity fragments can cause blinding eye injuries.

People should also wear sunglasses for UV light protection. UV light can cause skin cancer of the eyelids and may worsen cataracts and macular degeneration.

Q: How does our eyesight change as we age?

Dr. Koozekanani: Even with otherwise healthy eyes, our eyesight changes as we age. People may develop refractive error—which requires eyeglasses to address—in childhood or adolescence, and these changes may continue into young adulthood. Normal aging causes changes that people begin to notice in their mid-40s or-50s. The cliché of people having to hold reading material further and further away until they “run out of arm” is true. The lens of our eye needs to change shape in order for us to adjust our focus from distance to near. The closer an object is, the more the lens shape has to change. As we age, however, the lens stiffens, and the closest distance we can focus to gradually moves further away from our eyes.

As we continue to age, our lenses begin to become cloudy—known as cataract. Cataracts cause blurriness or glare, and may also cause refractive changes. With age, macular degeneration may also develop. This can cause blurry or distorted vision, and can cause missing areas in the central vision.

Q: How do aspects of our physical health, such as diet, influence our eye health?

Dr. Koozekanani: Our diet is very important to our eyes, both directly and indirectly. Some research shows positive effects on eye health from diets rich in omega-3 fatty acids. Foods rich in vegetables—especially vegetables that are dark green, red, orange or yellow—contain lutein and other substances which are healthy for your eyes. The popular wisdom that carrots are particularly good for your eyes has a kernel of truth. Carrots can prevent vitamin A deficiency, which can lead to night vision loss and blindness. However, if you do not have vitamin A deficiency, carrots will not make your vision even better than it already is.

Diets which prevent diabetes and high blood pressure can indirectly help vision by preventing the damage these conditions may cause to the eyes. Exercise also helps in this indirect way. Diet and exercise are good for cardiovascular health and have been shown to be helpful for age-related macular degeneration. Smoking harms the entire body, and the eyes are no exception. Smoking has been shown to worsen age related macular degeneration, cataract and optic nerve disease.

Q: Does looking at a screen for too long hurt our eyes? Do blue light glasses actually help?

Dr. Koozekanani: Any prolonged staring and concentration can cause eye strain. This is often the result of eye dryness or ‘dry eyes.’ Prolonged concentration and staring causes an involuntary reduction of our blink rate, which causes our eyes to dry out. This may cause a sensation of eye fatigue, eye irritation or eye watering. Sustained effort to focus our eyes may also tire the internal muscles which adjust our eye focus, causing a sensation of fatigue or headache. An incorrect eyeglass prescription or poor lighting may also cause us to strain more to do our work and worsen eye strain symptoms. Taking regular breaks to allow our eyes to rest can help alleviate eye strain. One approach is the 20-20-20 rule: after 20 minutes of work, look at something more than 20 feet away for at least 20 seconds.

Despite discussion in popular media, there are no convincing studies proving eye damage from blue light emitted from screens. Eye strain from screens is more a result of people using the screens for long periods without breaks, not because of the blue light from those screens. Blue light glasses are not advised according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology.

Q: What work are you doing to further research about healthy vision?

Dr. Koozekanani: My research entails ophthalmic imaging technologies. I have a particular interest in using computers to help automatically interpret ophthalmic images and make diagnoses from those images. One way we do this is through computer software that detects diabetic retinopathy—eye damage from high blood sugar—from eye photographs. This might allow patients to be screened for diabetic retinopathy while at their primary care doctor, allowing early referral to ophthalmology. As it currently stands, many patients with diabetes do not obtain their recommended annual eye exam and many suffer permanent vision loss before it is detected.

Dara Koozekanani, MD, PhD, is an associate professor of ophthalmology and retina fellowship director at the U of M Medical School. He treats patients with vitreoretinal issues, including macular degeneration and retinopathy of prematurity, as well as patients with diabetic eye disease and tumors of the eye. Dr. Koozekanani is helping to train the next generation of ophthalmologists and retina specialists in his role as the Retina Fellowship Director at the Medical School.

Dr. Koozekanani has a PhD in biomedical engineering and has research interests involving ophthalmic imaging technology and computer-assisted image interpretation and automated diagnosis from medical images.

-30-

About “Talking...with U of M”

“Talking...with U of M” is a resource whereby University of Minnesota faculty answer questions on current and other topics of general interest. Feel free to republish this content. If you would like to schedule an interview with the faculty member or have topics you’d like the University of Minnesota to explore for future “Talking...with U of M,” please contact University Public Relations at unews@umn.edu.

About the University of Minnesota Medical School

The University of Minnesota Medical School is at the forefront of learning and discovery, transforming medical care and educating the next generation of physicians. Our graduates and faculty produce high-impact biomedical research and advance the practice of medicine. We acknowledge that the U of M Medical School, both the Twin Cities campus and Duluth campus, is located on traditional, ancestral and contemporary lands of the Dakota and the Ojibwe, and scores of other Indigenous people, and we affirm our commitment to tribal communities and their sovereignty as we seek to improve and strengthen our relations with tribal nations. For more information about the U of M Medical School, please visit med.umn.edu.