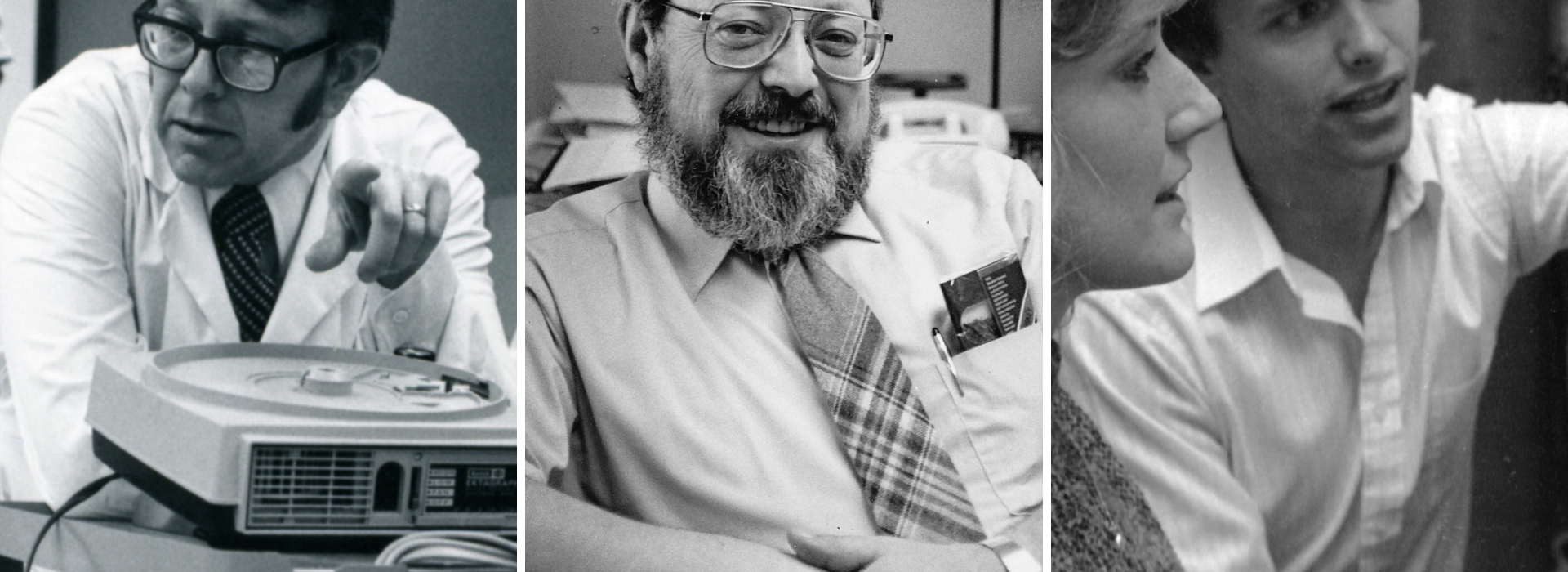

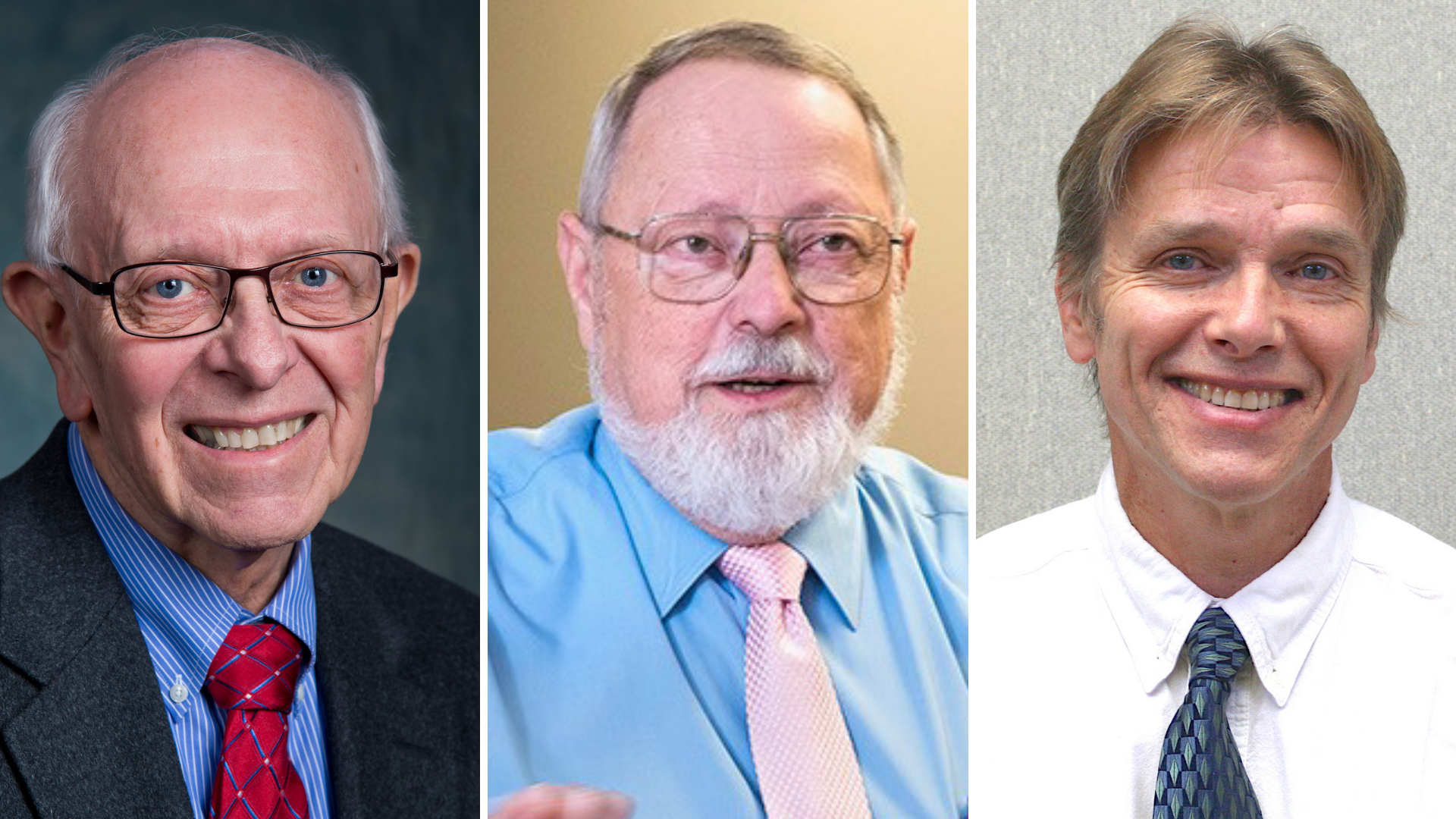

Three Long-time Duluth Campus Faculty Members to Retire

In 2021, three long-time faculty members who have been incredible members of the University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth Campus will retire — Dr. Jim Boulger (47 years), Dr. Arlen Severson (48 years) and Dr. George Trachte (38 years).

Jim Boulger, ’69 PhD

“The community made the school, and the campus thrived because of the people,” said Jim Boulger, ’69 PhD, a Distinguished University Teaching Professor in the Medical School’s Department of Family Medicine and Biobehavioral Health. “So many good things have happened since the Duluth campus has opened. Back then, there were fewer female students. This reflected the times and the suppression of women. Eventually, Duluth was among the first of schools to have an equal gender count in each class. It’s something to be proud of as well as meeting the mission of training rural physicians.”

When looking back at the early days, Dr. Boulger recounts the time when the University president called him to meet in the Twin Cities to talk about upcoming budget cuts, which threatened to close the school. “Cuts are people,” he said. “These were my colleagues and my friends. But what we had, and still have, is a connection with each other. It’s a unique and amazing quality.”

By the end of that legislative session, there were cuts but the Duluth campus survived. In many ways, the members of the campus community thrived as staff and faculty worked hard to make the mission a reality.

“My favorite part about my work? The students and their questions. It was a gift watching students progress from medical neophyte to competent caregivers. My job was to make the learning process as enjoyable as possible while upholding the highest standards of professional training — promoting curricular changes, following appropriate and rigorous study of how well current methods and content were promulgated and absorbed. I loved it. The best part were the ceremonies of educational achievement, including White Coat Ceremony, post-Boards parties, Match Day, graduation, practice entry and further development throughout the careers of our colleagues. Every bit of it means something, and it has been a wonderful career to experience with so many people.”

Originally, Dr. Boulger was born and raised in Minneapolis. He pursued his undergraduate degree at the College of St. Thomas followed by graduate work that led to a doctorate degree in psychology and child development at the University of Minnesota in 1969.

“I then took a position at the Medical College of Ohio in Toledo,” he said. “It was a brand new place, and it was when family medicine had just been approved as a medical specialty. That was something else to be a part of and to engage in as the curriculum developed and became more robust through the years.”

When he eventually landed in Duluth, he was drawn to the legislatively set mission to train family physicians who would serve rural populations. “This wasn’t just another medical school,” he said. “It had definite missions, and the faculty added the Native American charge in 1974. This was a necessary and important addition to our service to rural communities. It’s also notable that the Duluth campus was a community-based environment looking at new methods of training the best physicians for all of us.”

Although the missions of the campus drove decisions and revisions, Dr. Boulger recalls how the design of the original curriculum required a cutting-edge mindset; a willingness to consider methods and procedures that did not fit the mold.

“There were endless versions written on ‘stickies’ and posted on the wall,” he said. “There was the push to include new material in the curriculum.”

Included in the considerations were programs that focused on family medicine, rural health and social disparities. At the same time, members of the campus community were experiencing questions from LCME visitors who wanted to understand why general practitioners were teaching students the curriculum.

“There were constant revisions to the educational programs. We needed to be current and effective, always seeking feedback from students even when changes suggested were not implemented due to the lack of resources. I was always thanking God for the patience of faculty and students as we all grew better in meeting the school’s goals.”

In 2019, Dr. Boulger was granted Honorary Membership in the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). According to the AAFP, he was the first non-physician faculty person honored with this award since Dr. Alexander Fleming, the discoverer of penicillin. Earlier in his career, he was also named the National Distinguished Rural Health Educator of the Year in 2002 by the National Rural Health Association.

During his 48 years teaching, leading and mentoring medical school students, Dr. Boulger fondly recalls alumni by name and specialty. He meets them long before they graduate, whether it is during the application process, orientation week or at many moments during their educational journey as instructor and supportive member of a thriving campus.

“My hope for alumni is that they always strive to take the very best care of all those who they love and who love them in return — families, friends, colleagues and patients. To remember that they were privileged to learn medicine from all of us in Duluth. The school is so proud of all that our alumni have done and will continue to do.”

Arlen Severson, PhD

“When I heard about the Duluth campus mission, I was honored when they hired me. When I first visited the area, it was January and 20 below that night. The vehicle I was in had a heater somewhere, but it was hard to tell,” said Arlen Severson, PhD, a professor in the Medical School’s Department of Biomedical Sciences. “I taught the first lecture of the charter class. It was Cell Biology, and we began right after Labor Day. At the time, I had written a 50-page neuroscience manual for the courses. It took a lot to get through during that fall semester, but we did.”

Fast forward to 2020, while looking back at a lecture where Dr. Severson taught about microcytes and macrocytes, he brought in three different doughnuts of varying sizes smothered in red icing.

“I used the doughnuts to teach about the development of blood. At the end of the lecture, I treated all the students to a box of doughnuts I had kept to the side. Just a couple weeks ago, my daughter surprised me with a box of doughnuts at my retirement party. All of them had red icing on them. This reminded me of that lecture, and it was great that she remembered it too. So many wonderful memories to celebrate,” he said.

Back in 1972, when Dr. Severson began to teach courses in Duluth, there were 24 students in the first class, which was a big difference from when he taught previously in Indiana, where each class consisted of 200 members.

“It was a big change. There were lab groups in Indiana where I worked closely with students and I got to know about 50 of them out of 200. In Duluth? We did not need lab groups to get to know our students. We knew all of them, and we connected with them. That has stayed true all these years,” Dr. Severson said.

Before he landed in Duluth, Dr. Severson learned a great deal by teaching similar courses at a medical school in Indianapolis that he eventually also taught in the northern state. While his original pursuit was physiology, support from mentors led him to anatomy.

“I grew up in Minnesota,” he said. “But, I took a year off while living and teaching in Indiana. I was mostly interested in research and took time to pursue my research through the National Institutes of Health (NIH). My sister who lived in Aitkin mentioned that a medical school was opening in Duluth. I contacted someone to confirm the news. Later on, Dr. John Leppi returned my call. He was recently hired at the school.”

As things would go, Dr. Leppi visited Dr. Severson while he was working with NIH, and they discussed the details about the campus opening. While it would be another year before Dr. Severson moved to Duluth, he understood the importance of opening a campus that catered to educating future family doctors. As colleagues and contacts had shared with him, there was a shortage of doctors in rural communities.

“I was already aware it was a challenge but hearing that Duluth had a school with a mission to meet that need, I was privileged to be with them from the beginning.”

Although a 48-year career in the Zenith city has many memories, Dr. Severson recalls with humor that a student in the charter class fell asleep during his microscopic anatomy course.

“He had his head against the wall next to his desk. We were on the lower campus at that time. Everyone knew he was asleep. I kept pointing at him with my laser pointer, and he eventually woke up. After that, I told a lot of Finlandian stories to keep students awake,” he said.

In the 1990s, Dr. Severson’s interests in neuroscience led him to develop and present a brain lesion program at an American Association of Anatomists’ conference. The program was then distributed as the first-of-its-kind that showed the nervous system in a complete and innovative way. The conference presentation paved the way for nearly 70 medical schools who implemented the program into their neuroscience courses. Although Dr. Severson was a part of this leadership evolution, he also learned how to improve his teaching skills by serving as a guest instructor in Florida.

“I heard that students were doing really well in neuroscience,” he said. “They did so well because their clinical cases were right after neuro lectures. We knew this at Mayo but going to Florida and seeing it applied to neuroscience classes taught me how to be a better instructor. My favorite course to teach was neuroscience. I think it’s because I see the system as a puzzle. It’s complex but from a clinical point of view, if you know the structure, you can make general diagnoses where the problem exists. I started in Indiana, taught twice at Mayo on a fellowship and I participated in neuro courses for most of my career.”

Even though Dr. Severson spent his multi-decade career in Duluth and enjoyed being a part of the first class and first circle of instructors, there were professional challenges along the way. The biggest one for him, the one that created a sense of loss and worth, was when students struggled and either eventually succeeded or realized a different career path was calling.

“Some students have a good science background, and others were weaker in the sciences,” he said. “Sometimes the challenge was helping those who were facing the most difficulty to learn the material. I worried about them. It was sometimes frustrating. Students worked hard and sometimes they didn’t make it because they had other things going on in their lives. It is not easy material to learn, and I was learning right along with them. For those who could not make it, it was incredibly hard to see them go, especially because of the small class sizes.”

As Dr. Severson recounted the past, the charter class continued to stand out to him with a number of firsts experienced by faculty, staff and students who eventually became alumni. When a student from the first class graduated, he then interned at St. Mary’s in Duluth. Afterward, he relocated to a rural community in Minnesota. He began his new position on the first of July. The other physicians took time off for the upcoming holiday. On the fourth of July, a car accident was reported in the region and an injured young lady was taken to the clinic where the Duluth campus alumnus had just started working.

“In order to save her life, he had to open her skull to relieve the pressure from the head injury,” Dr. Severson said. “She would have died if he hadn’t done it. The nurses helped him immensely, and later on when he told me the story, he knew he couldn’t have done it without their help. This was during his first week in a rural area. This is why I loved teaching. Knowing that the skills I taught would give my students the knowledge they needed to care for their patients. I’ll miss helping students the most. My students in a dissection course gave me a large pair of scissors with my initials engraved as a goodbye gift. I was always telling them to use the largest pair they could find. I’m glad they listened to me.”

George Trachte, PhD

George Trachte, PhD, a professor in the Department of Biomedical Sciences, began his professorship in 1982 and taught a series of courses focusing on cardiovascular and respiratory medicine as well as a plethora of other subjects, including the musculoskeletal system. Among students and alumni, he was also known as the professor who encouraged and supported the ice skating team that continues to this day in Duluth.

As we celebrate this momentous occasion, consider supporting future students by making a gift in honor of our three faculty retirees. A special fund has been created in honor of their retirement. If you would like to learn more about this giving opportunity, please contact Elizabeth Simonson, director of development, at esimonso@umn.edu or 218-391-4772.