World’s First-Ever ECMO-based Clinical Trial Shows Six Times Higher Survival Rates Among Cardiac Arrest Patients

Hospital systems worldwide will now rethink the standard of care for patients under cardiac arrest thanks to new results from a clinical trial led by the University of Minnesota Medical School. Funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) supported this research — published in The Lancet — as the first clinical trial in the world to show a significant increase in survival rate among patients experiencing cardiac arrest who received treatment from the life-support machine known as ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation).

“ECMO proved to be so much more effective — in fact, patients were six times more likely to survive with ECMO — than the standard treatment for cardiac arrest that the trial was stopped early after enrolling just 30 of the expected 77 patients,” said Demetri Yannopoulos, MD, a professor in the Department of Medicine, director of the Center for Resuscitation Medicine and the lead investigator of the trial.

According to a release from the NHLBI, some 340,000 people die of cardiac arrest each year in the U.S., and less than 10% of people who experience it survive. The condition occurs when the heart suddenly stops beating, leading to a loss of blood flow in the body, including the heart and brain. Without immediate and effective emergency treatment, many die.

Typically, that emergency treatment involves CPR, defibrillation, intubation and intravenous medications. But when using ECMO as part of a larger system of care, this study showed that six of 14 patients (43%) survived to hospital discharge compared to just one of 15 patients (6.7%) who received only the standard treatments. After a unanimous recommendation by the independent data safety monitoring board, the NIH stopped the study early because the probability that ECMO was superior to the standard treatment, based on the results of the first 30 patients, was 98.61%.

“As such, it was deemed unethical to continue randomizing patients in the standard ACLS group,” Dr. Yannopoulos said. “Many people don’t respond at all to the standard treatments, and that’s likely because these patients had severe and extensive blockages in the arteries in their heart. When we’re too busy doing CPR, we’re losing time to address the actual problem of the cardiac arrest, which is likely their blocked arteries.”

ECMO affords physicians more time to clear those blockages while taking over the function of the patient’s heart and lungs. After hooking a patient up to the machine, it pulls blood out of the patient’s body, pumps it through part of the machine that acts as an artificial lung and returns it back to the body. Yet, Dr. Yannopoulos emphasizes that ECMO alone is not the reason behind the increase in survival rate.

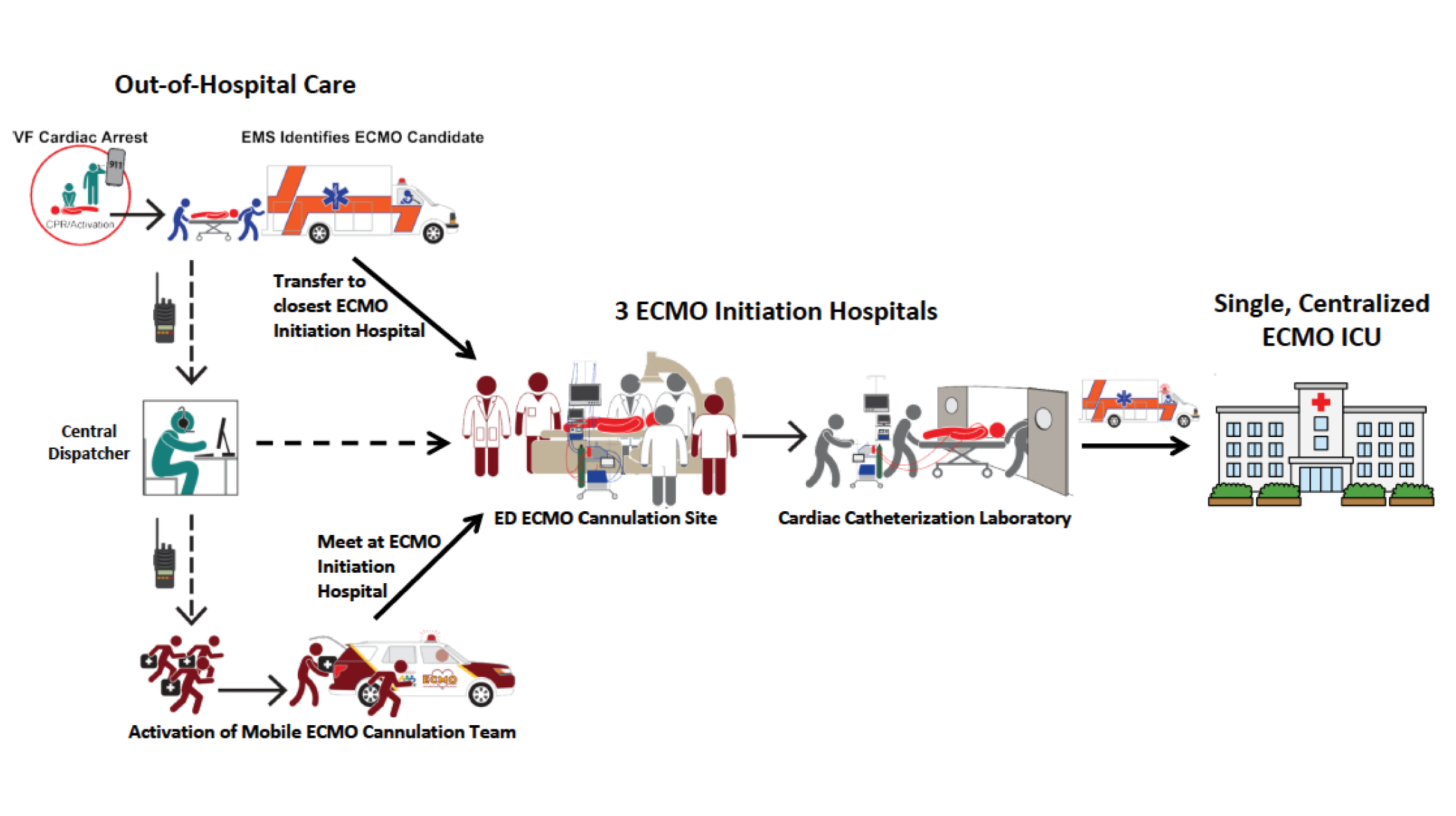

“It’s the team program we built around using ECMO,” he said. “We developed protocols for emergency medical services to quickly identify patients who need ECMO and created avenues for rapid communication with an ECMO center to mobilize help. The findings from this clinical trial make an important statement that early implementation of ECMO is the enabling and necessary condition that allows further advanced targeted therapies to be delivered to those patients. In its absence, the life-saving treatment that follows is just not possible.”

Among those in the trial, 25 of the 30 patients were men, and all participants averaged around the age of 59. Although the trial ended early due to superiority in the results, the team stayed in touch with the surviving patients. Six months after the surviving patients left the hospital, all six ECMO patients had improved both functionally and neurologically, returning to a near-normal life with either no or very small disabilities. The one patient who survived after receiving only the standard of care died two months after hospital discharge.

“After the last five years of studying ECMO at the University, we knew it would be very effective but just not how effective in comparison to current treatments,” Dr. Yannopoulos said. “The next question is, how do we make this translational for other communities?”

In a separate study also published today in EClinicalMedicine, Dr. Yannopoulos and his team with the Minnesota Mobile Resuscitation Consortium detail the outcomes over the last four years of the ECMO-facilitated resuscitation program that has served the Twin Cities area.

“Our system is translational, but the components we have within our program are currently unique,” he said. “The idea is that you can create a single unit with highly specialized physicians and a medics team that respond to all cardiac arrest emergencies for all the hospitals from a central location. Because the time sensitivity is so critical, this system has to be built into the emergency response infrastructure of the city. Our second study, which was funded by the Helmsley Charitable Trust, basically describes how that can be done, and we’ve provided a blueprint for how other communities can adopt this life-saving system.”