Medical School Team Helps Develop World’s First AI-Controlled CPR System

Since 1960, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) has remained as the most immediate course of action for those experiencing cardiac arrest. Yet, for 60 years, despite the progression of medicine elsewhere, the technique remains largely unchanged—until now.

A team at the University of Minnesota Medical School and the Georgia Institute of Technology has invented the world’s first artificial intelligence (AI) closed-loop CPR system. Early studies show the system performs better than both a licensed physician and the LUCAS machine, a mechanical chest compression device, during a cardiac arrest when a person’s heart has stopped.

“The issue with CPR is that after 20 to 25 minutes of CPR, the chances of surviving are in the single digits,” said Demetri Yannopoulos, MD, professor in the Department of Medicine’s Center for Resuscitation Medicine, who helped lead the project. “While CPR can maintain blood and oxygen supply to the brain, which is the most sensitive organ to the lack of oxygen, it unfortunately provides only 10 to 20% of blood flow initially, then deteriorates over time.”

For the last 20 years, Dr. Yannopoulos has studied resuscitation medicine and over time he began recognizing a critical need to rework CPR’s “one-size-fits-all” approach. To discover if AI could play a role, he partnered with an aerospace and computer engineering professor, Evangelos Theodorou, PhD, at Georgia Tech, and together, they funded and formed a team between aerospace engineering students at Georgia Tech and members of Dr. Yannopoulos’ lab, including third-year medical student Pierre Sebastian who led the project team at the U.

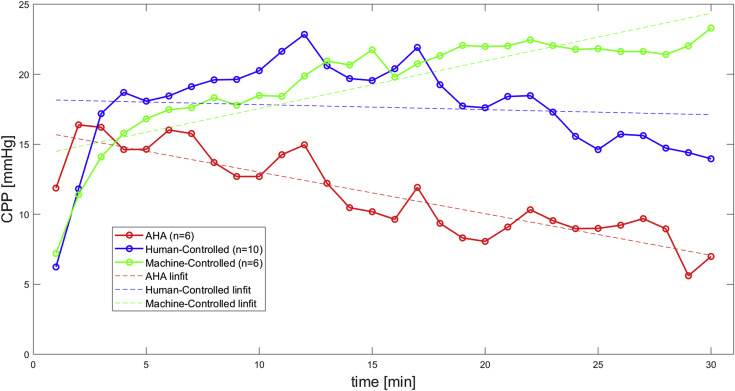

The group trained their algorithm in pre-clinical studies on over 100 pigs, ultimately noticing superior coronary perfusion compared to other CPR methods. At the 15-minute mark, as the CPR provided by the physician and the LUCAS machine trended downward, the AI machine-controlled CPR trended upward and stabilized at higher rates of coronary perfusion pressure.

“This computer outperforms physicians who could manipulate the same patterns of CPR while knowing the same information that the computer does,” Dr. Yannopoulos said. “It has the ability to calculate and assess data a million times per second, learn from what it does and then predict the future to optimize the simple concept of chest compressions. A human brain simply cannot do this.”

Over the next three years, Dr. Yannopoulos and the team will continue to optimize their algorithms. This initial study only focused on the depth of chest compressions and decompressions, but he said many factors, not yet incorporated into the algorithm, impact the success of CPR, including compression rate, depth and timing.

“The next steps for us are to study how this machine can now incorporate all of these other components to further improve the ability to perform CPR,” Dr. Yannopoulos said. “We have a plan to apply for grants, where we will bring together all of these other components. Imagine how much more complicated the algorithms will become—almost impossible for a human being to understand.”

For Sebastian, as a medical student, the opportunity to partner with a diverse and multidisciplinary team “attempting to change a paradigm of medical therapy” is a long-time dream come true.

“It would never have been possible without the collaborative efforts of Georgia Tech,” he said. “They've brought their full machine-learning expertise to the project, and unique collaborations like the one we've created here are what really push the envelope of medical discovery.”