Interdisciplinary Innovation Brings 3D/Virtual Reality Training to Orthopedic Residents

In orthopedic surgery residency, practice makes perfect. Trainees learn how to perform procedures through a combination of in-person training with faculty, practicing on cadavers and exploring anatomy in a simulated environment using sawbones or orthopedic models. Some elective procedures and clinics have been limited during the COVID-19 pandemic, as have simulation environments, and as a result, medical students, residents and fellows have less time in the operating room.

“As we made adjustments to our residency program in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, our goal was to continue to train our learners via a robust curriculum,” explained Assistant Residency Program Director Alicia Harrison, MD, an assistant professor in the University of Minnesota Medical School’s Department of Orthopedic Surgery. “Simulation has been a focus of our program for quite some time, but we have never used it in a socially distanced environment.”

Dr. Harrison, along with Marc Tompkins, MD, an associate professor in the department, recognized the potential to utilize 3D and virtual reality (VR) software to improve resident procedural training in partnership with the Earl E. Bakken Medical Devices Center (MDC). In early May, the interdisciplinary team’s project proposal was funded by a U of M Medical School COVID-19 Medical Education Innovation Grant, created to move small-scale research and education projects forward.

Dr. Tompkins has a keen interest in applying 3D/VR and augmented reality (AR) in medicine and has a history of collaboration with the MDC, including Muhammad Ahsan, a programmer, and Paul Rothweiler, the prototyping and materials coordinator.

“Because of our previous collaboration, we knew the MDC’s capabilities from a VR and 3D standpoint,” Dr. Tompkins said. “We realized there were tools our residents could use while they’re not getting as much hands-on training.”

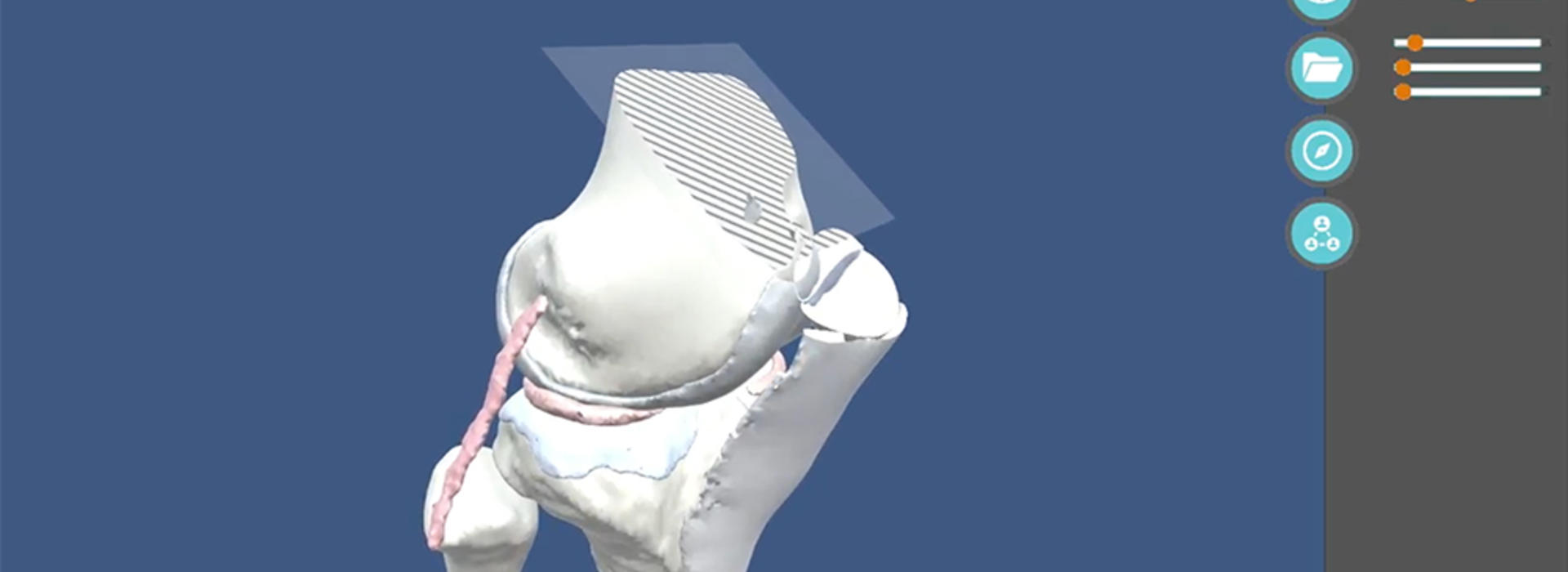

The multi-faceted project includes a web-based program that allows trainees to view a surgery on a split screen showing the related 3D anatomy. It can be manipulated and explored through the 3D program on a 2D screen or with a virtual reality headset.

“The 3D software helps trainees get a sense of the overall shape and relative anatomical relationships,” Dr. Tompkins said. “They can familiarize themselves with the anatomy in a way they wouldn’t otherwise be able to, all from their own computer.”

The software is also useful in terms of surgical planning, templating and mastering implant placement using a patient’s actual anatomy from a CT scan. This is particularly important for procedures like shoulder arthroplasty because understanding the 3D orientation of implants and anatomy is critical before performing one.

“The platform we are developing teaches a learner the correct implant placement virtually in a low-risk environment,” Dr. Harrison added.

The grant will also support printing 3D hand models to enhance skills such as pinning scaphoid and metacarpal fractures—a requirement for graduation—from home. The MDC’s state-of-the-art J750 3D printer uses sophisticated polymers that mimic actual bone and tissue density.

“Right now, working on skills using a cadaver could be difficult,” Rothweiler said. “Instead, we can send a 3D printed hand to practice on while simultaneously viewing the surgery and anatomy online, engaging all the learning senses.”

The team’s first goal is to validate the tool, which includes showing that the software makes a difference in performance and can measure skill. The next step is assessing transfer validity—evidence that the tool makes a difference in how the trainee or surgeon performs a task in the operating room.

“Simulation is critically important while learning from home, but it also has a role in education beyond our current circumstances,” Dr. Harrison said. “Research has shown that simulation training helps everyone, even experienced surgeons.”

Surgical simulation in orthopedic surgery has been required by the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) since 2013, although the specific simulations, frequency and duration are left to the discretion of residency program directors. Adapting to new ways of learning and interacting are some of the critical changes that have come out of the COVID-19 pandemic so far.

“A lot of innovation happens during unforeseen circumstances,” Ahsan said. “The Medical School’s rapid response grants support novel concepts, and while the solutions apply to a remote teaching environment, they brought to light improvements in education long-term. While the MDC can conduct research and develop technology, this wouldn’t have been possible without physician collaboration and input.”