SCI Researchers Engineer Special Cell to Kill Cancer Tumors

The immune system works constantly to protect us from the inside, fighting off the common cold and even cancer. As our cells grow and divide, genes inside the cells can undergo mutation, causing the cells to grow abnormally to form tumors or cancer. But, instinctive help from white blood cells—the immune cells in our blood—works to search for and destroy these abnormal cells before they become a problem. These mutated cells, however, are also very clever and can evolve in ways that allow them to evade and escape immune surveillance.

It’s this understanding of the immune system and cancer biology that is at the core of today’s cancer immunotherapies. One particular immunotherapy, called FT516, is the basis of a clinical trial that launched at the University of Minnesota last fall. It’s the first-ever, FDA-approved clinical trial using genetically-engineered, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) to treat various types of cancer—a concept with ties to research that began at the U of M Medical School’s Stem Cell Institute (SCI).

Merging Critical Expertise

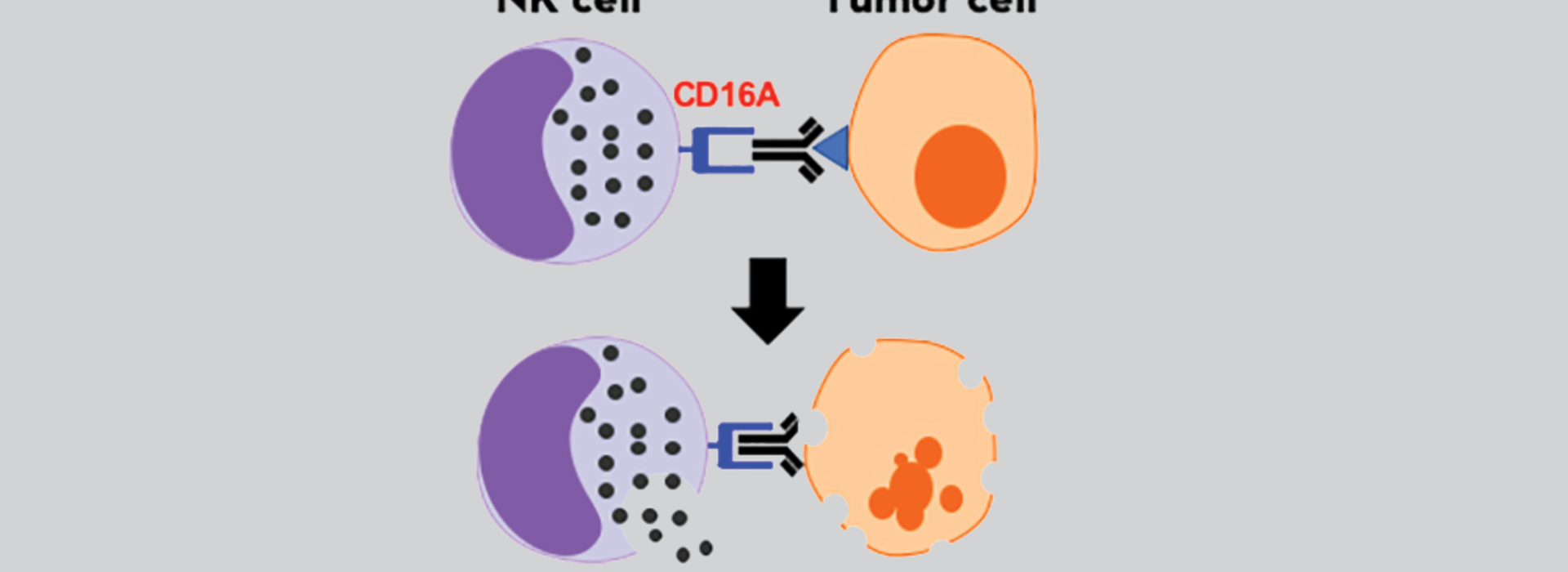

Jianming (Jimmy) Wu, DVM, PhD, joined the College of Veterinary Medicine in 2010 as an associate professor where he met fellow faculty member Bruce Walcheck, PhD, a professor and member of the SCI. They began studying a particular receptor, called CD16, which is critical in the function of a special type of white blood cell—the natural killer (NK) cell. This immune cell has a key role in killing mutated cells in our bodies, including tumor cells, but it can lose this much-needed CD16 receptor while responding to tumor cells.

“This receptor is regulated by a protease (an enzyme), and through our work, we genetically engineered this receptor so that it will no longer be cleaved (or clipped) by the protease and thus, remain on the NK cell to perform its function of binding to antibodies,” Dr. Walcheck said.

With this modified receptor, the duo partnered with former faculty member Dan Kaufman, MD, PhD. He brought expertise from the University of Wisconsin, Madison where he worked alongside biologist James Thomson, PhD, to become the first to isolate and characterize human embryonic stem (ES) cells in 1998. By 2005, now at the U, Dr. Kaufman was the first to derive blood cells from human ES cells, ultimately, leading to the key discovery for his new partnership with Drs. Walcheck and Wu—how to make NK cells from iPSCs.

“That was an important advantage because the iPSCs are very amenable to genetic engineering, so this allowed us to put our modified CD16 receptor, into these cells and then derive NK cells that are expressing our new, enhanced receptor,” Dr. Walcheck said.

Meeting Their Fate

The team continued to improve the process—both in enhancing the modified receptor and improving the efficiency in developing NK cells from iPSCs. By 2016, they partnered with Fate Therapeutics, a biopharmaceutical company in San Diego, Calif., to develop the immunotherapy they hope will prove useful very soon.

“By expressing our enhanced CD16, the Fate Therapeutics product is, as far as we know, the first-ever, genetically-engineered, induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cell therapy approved by the FDA and is being used in a clinical trial at the University of Minnesota,” Dr. Walcheck said.

This cell therapy of “an enhanced white blood cell population” can be delivered to patients in different ways—directly into the blood system (intravenously) or where the tumor resides in a specific tissue location. Dr. Walcheck says it depends on the type of cancer being treated.

“Jimmy and I have been working on the next generations of this receptor so that it binds to the anti-tumor antibodies and signals to activate the NK cells even better,” Dr. Walcheck said. “Our understanding is evolving, allowing us to improve the engineered receptor to hopefully make NK cells even more efficient at killing tumor cells.”

Their studies on the CD16 receptor also has implications for destroying virus-infected cells, like HIV, and Dr. Walcheck says, “Hopefully, in the future, we can move from cancer to immunotherapies for infectious diseases.”

It’s a promising future he says would not be possible without team science and the unique collaborations and resources available through the SCI.

“The various institutes and centers at the University of Minnesota are very important in bringing expertise together, providing shared instruments to use and organizing seminars to bring researchers and physicians together with their different expertise and opinions,” Dr. Walcheck said. “Jimmy and I had these ideas, and then we found others with expertise who could help us develop them. The Stem Cell Institute is one particular mechanism that helped us do that, and the take home message is: team science is very important.”

This year, the SCI is celebrating its 20th anniversary and the promise for the future. Learn more about the SCI on their website.