U-developed Antibody Test, Key Component in Reopening Minnesota

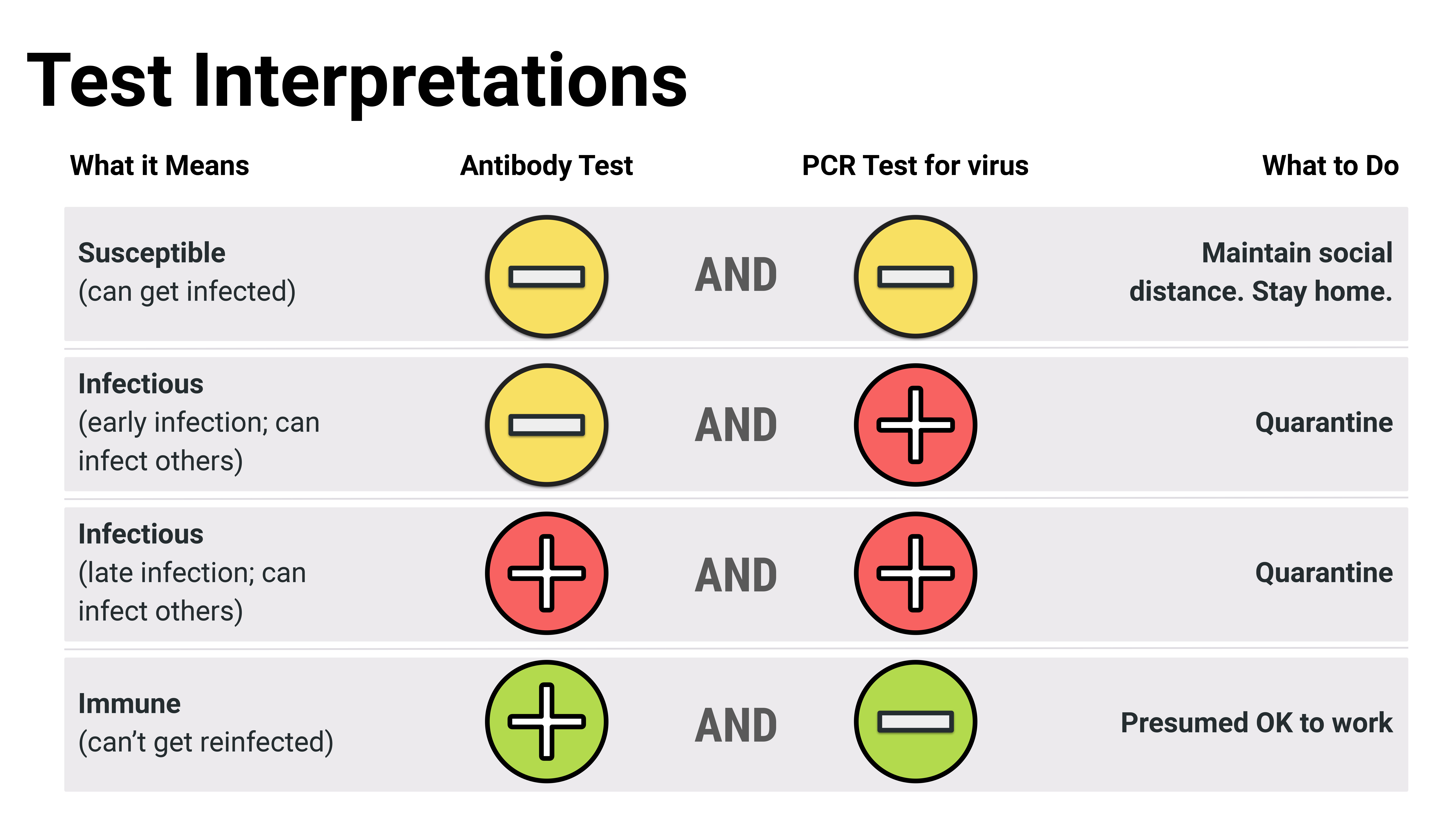

A second test for COVID-19, developed by University of Minnesota Medical School researchers, will play a role in the state’s plan to reopen Minnesota. This test looks for antibodies generated after exposure to the virus, and combined with the University’s diagnostic (PCR) test, helps categorize those tested into four categories—information that will equip the state to confidently send Minnesotans back to work.

Together, they are informative if you do them both in the same person,” said Amy Karger, MD, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology. She leads the team at the University’s Advanced Research and Diagnostic Laboratory (ARDL) that brought the test from a research setting into clinical use.

“If both tests are negative, then there’s no current or past infection. If the PCR test is positive and antibody test is negative, then they have a current infection but just haven’t mounted an immune response yet. If both tests are positive, then they have an active infection with the start of an immune response. If the PCR test is negative and antibody test is positive, that’s a sign of a past infection, but there’s no active virus,” Dr. Karger explained. “We’re really trying to get providers and clinicians to view this antibody test more as a tool for determining if someone has been exposed.”

It’s also a test not vulnerable to today’s supply chain issues. The collection process involves drawing blood into vials (no need for low-supply nasal swabs), and the procedure itself uses routine laboratory supplies not in high demand.

The Minds Behind the Antibody Test

The antibody test, known as an ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay), developed rapidly from the lab bench to the clinic with the help of a unique group of collaborators—Dr. Karger, Marc Jenkins, PhD, and Fang Li, PhD.

In March, Medical School leadership tasked Dr. Karger, who is M Health Fairview’s system director for point-of-care testing, with reviewing the validity of the emerging, commercially-available antibody tests.

“And, the answer every time was no. None of the tests that were coming out looked like they were reputable,” Dr. Karger said. “We were getting calls and emails daily, sometimes from companies we’d never heard of before.”

Around that same time, Dr. Jenkins, a Regents and Distinguished McKnight University professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology and director of the Center for Immunology, proposed an idea to Medical School Dean Jakub Tolar.

“I told him that the University should develop its own test to avoid supply chain bottlenecks,” he said.

Dr. Jenkins had learned of a new antibody test created by a group at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City and was also aware that Dr. Fang Li, an associate professor in the College of Veterinary Medicine, a coronavirus expert, had the expertise needed to produce a key ingredient—a SARS-CoV-2 protein.

“If we did not have Fang Li’s protein-production capabilities online here, where he can make us many milligrams of protein very rapidly, this would be a non-starter,” Dr. Karger said. “For other institutions who don’t have Dr. Li, that piece can take months, frankly, if you don’t already have the set-up to make the protein, so this is very unique for the University.”

From the Research Lab to Bethesda Hospital

Once Dr. Jenkins and his lab had validated the antibody test in a research setting, he relied on Dr. Karger to translate the test into clinical use. As a principal investigator associated with ARDL, she recommended housing the antibody test there—a nationally-renowned clinical trials laboratory, specializing in more manual tests.

“The reason I suggested ARDL, and why that was quickly supported, is because ARDL does so much already with research and innovation in testing, and they are very experienced in doing this type of thing where they bring a test in and validate its performance,” Dr. Karger said. “It’s a manual test, whereas most of our clinical labs deal with very automated testing.”

The team worked tirelessly to bring up the test in ARDL, receiving training from the researchers in Dr. Jenkins’ lab, who had, for the last few weeks, built the test from scratch.

“The lab staff are really the engine behind this whole process, and they were putting in 12- to 14-hour days, seven days a week to accomplish this. I have been so impressed to see the dedication of these people who are willing to just give it their all and work well beyond what would normally be expected for their work hours,” Dr. Karger said.

Dr. Jenkins added, “It was incredible how quickly ARDL got the test up and running.”

On April 16, now with the antibody test set up in ARDL, the research team began testing samples from employees at Bethesda Hospital—M Health Fairview’s designated COVID-19 care facility. Starting the tests with this group, who have regular exposure to COVID-19 patients, will provide valuable information as the ARDL team develops a larger plan to scale-up the test for statewide use.

“Right now, because the test is new, we are only using the antibody test to determine who is positive in Bethesda and may need to get a PCR test to check for current infection,” she said. “This information is useful while we formulate a final plan for how to really roll this out in a more broad sense.”

Scaling-up for Statewide Testing

On April 22, Gov. Tim Walz announced the state would allocate $36 million to the University of Minnesota and the Mayo Clinic in support of a plan to begin testing 20,000 Minnesotans per day, starting with all of those who are symptomatic.

“This allows us to purchase much larger-scale automation that can complete tests at a rapid rate, as well as hire on and train a larger staff,” Dr. Karger said.

She says the next steps will be planning for how and where to set up collection sites, how those samples get to ARDL and then, how to get those results to hundreds of thousands of people in an efficient way.

“I don’t know what the crystal ball will show, but I do think testing is going to help us have a better sense of what the future will hold,” Dr. Karger said. “If we can get a handle on how many people have truly been infected, we can go from there in terms of planning and what we can expect for the future.”